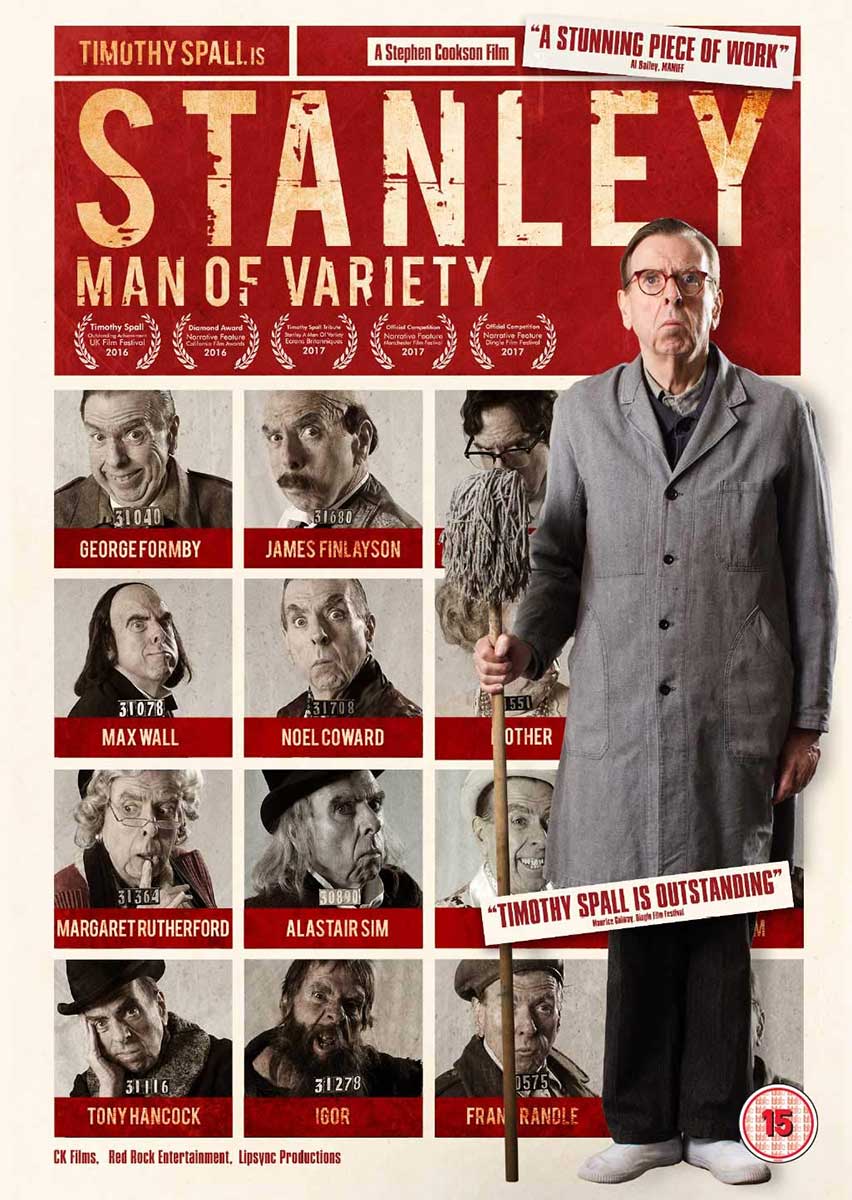

In Stanley, A Man of Variety you play a range of British comedy legends such as Max Wall, Tony Hancock, Max Miller. Were they your comedy influences?

They are people I grew up with, watching on the telly. There were only two channels when I was a kid. On a Sunday and it would be The Big Picture, and some of them were 40 years old. As a child you don’t know that, but you know there’s something odd about it. So it tied in, in the film, with a sense of the feeling of those characters, as well as their performances. A connection with a period of isolation; the kind of world that postwar Britain was. With the film we wanted to portray the connection between the so-called affable, charming, unusual, erratic British characters, but a subversion of that and showing something more underneath, something more.

They don’t seem like impersonations, more like interpretations of each comedy character?

Yes, all the stuff we wrote was inspired by the essences of their character. For instance, when Hancock talks about how he killed himself through drink, and Margaret Rutherford puts him on trial and confuses his chamber pot in killing John Wilson. It turns out that Margaret Rutherford’s father killed his own father with a chamber pot in real life. There’s a bending of the affability of them.

You did Alistair Sim but not Peter Sellers? Were there any characters you originally wrote in and then ditched?

We did the ones I thought I could have a crack at. When Stephen and I sat down and started to try and build this film, those characters introduced themselves. As the picaresque journey of the story evolved, the characters turned up to take him on to the next thing. We didn’t want it to be a series of turns, like the Mike Yarwood Show. The story is about a man with no sense of humour, actually, and a man of very little character. A nobody who has all these people in him. The comedy characters are all part of his own guilt, his confusion.

I suppose the Indian doctor is the best example, as Stanley’s version of him verges on racist and the doctor then challenges him on that.

Indeed. He started as a kind of Peter Sellers in the Party, which now would be completely unacceptable but was very entertaining at the time. But we made him much milder, and when Stanley sees him, he accuses him of what he thinks he’s feeling, which is what he’s feeling himself. I’m glad you got that. It’s not meant to be a funny film, but if it’s uncomfortable, even better!

In terms of funny, I thought the Max Miller scene was laugh-out-loud funny and I could have watched a whole film of you doing Max Miller.

I love the fact that music hall characters directly link to that grotesquery, that grand guignol that goes right back to comedia del arte. Music hall is also attached to our English literature, Dickens in particular, and also the fairy stories of Hans Christian Anderson.

Do you think every actor yearns to do a Kind Hearts and Coronets? The type of film where they play all the characters?

I wouldn’t say it was a common desire. Possibly the desire of people who are driven to be other people. There’s a fine line between wanting to show off and show what you can do and trying to get inside other people, see where their idiosynchrasies are, where they’re coming from inside. It’s more of a compulsion than a desire. I suppose you could say that getting up in the morning and walking about in the street and talking to people is one form of solipsistic egotism. Acting takes it much further, because what you’re doing is exercising this desire to understand why people want to be other people, like a novelist does. It’s trying to get inside someone else’s mind and presenting it. It’s all an offshoot of trying to work out what it is that makes people tick; what is the motor to the tapestry of their idiosynchracies.

You have played a lot of characters who really existed. Is this easier than playing fictional characters or more challenging?

It’s both liberating, in that you’ve got a figure you’re aiming at, but it’s also restricting because you know that person is well-known and they have a view about them. So you’re making a rod for your own back, because people might say, oh, you didn’t get him; it’s just an impersonation. So you have a template for somebody you’re going into, it’s your job to find out where those characteristics come from. So I always stare at pictures of them, and if I can find photos of them as children and then young adolescents, I can get a lot of insight into them. When I played Ian Paisley, for example, this big, terrifying firebrand, I found this picture of him when he was about 16. He’d had a growth spurt, and his trousers were a bit too short for him; he was all clumsy and he had a huge head. There was something so deeply touching, seeing how he grew up around that. It showed a vulnerability, it makes you wonder what was the next slice of the gateaux of their life. Because it’s still in there; you’re still that child.

It sounds like you almost have to grow up with them, to get a sense of who they are when you’re playing them? That’s pretty deep research.

Yes, but once you’ve found out all you can about them, you have to take a massive leap of the imagination. And then there’s the extra thing, whether it’s right or wrong, where you try and connect your soul with their soul. And I don’t mean that in the profoundest way. Then it stops being an impersonation, and it becomes an almost abstract thing. It’s like when I did David Irving [in Denial, 2016], it was my job not to judge him from an objective point of view. If you’re liberated by playing someone who never existed, you have to make them look as if they actually might have existed. So you have a blessing and a curse of playing somebody who is real.

Was David Irving the most morally horrible character you’ve played?

Well it depends where you stand. I’ve played lots of characters who aren’t deemed as such but a lot of people might consider so. Somebody who’s become a pariah like Mr. Irving, who was an incredibly respected historian and became this mouthpiece for very unappealing and offensive ideals, damaging, toxic views, then I’m fascinated by them. How the perceived view of them compares to what they’re actually like. What they become because of a cause-celebre of some description, and how much of their public persona that is seemingly vile is real, or is it an accretion of the thing they’re involved in, or did they become that because people want them to. It’s like Donald Trump, so many people look at him and loathe him and think he represents all that’s vile, and then there are a load of other people who think he’s the bees knees.

Was John Polidori in Ken Russell’s Gothic the the maddest character you’ve ever played?

He was an interesting, damaged, foppish character who ended up killing himself, friend of Byron and so forth. But recently I’ve tried to go for characters who are at the centre of the piece, people like Turner and Lowry, who I’ve just played. I am drawn to the extreme; I suppose I’ve got one of those faces that lends itself to people who are unusual. When I was 20 at RADA, I loved playing different characters. In the first two months there I played a colonel in a Peter Schaeffer comedy, and a Geordie trade unionist. Things are be put into your DNA at that age about what you’d like to end up doing in later life, and that pattern was established.

Two extreme ends of the British class system. Everything in between that is the whole of England, isn’t it?

Yes, that’s a lovely thing, being tolerated. In a country that, as soon as you open your gob, you’re defined by where you’ve come from. All you’re trying to do is turn up in a movie, and for people to believe that you exist right in that moment and the illusion and suspension of disbelief. Making that a real living creature is part of your job.

As Turner, you seem to inhabit the role with a Dickensian glee and you look very comfortable in a top hat. Do you favour the Victorian period, or are those just the roles you get offered more?

I have a massive love of Dickens and the Victorian period, and the early 19th century. It was the golden age of English literature. It’s interesting that Britain at its most repressed gave birth to this amazing boiling up of what was going on underneath. It’s a bit like when you go to New York and it’s defining period was the 1930s and 40s, with the Art Deco architecture, everywhere there’s a flavour of that period. Then when you walk around London we have these fantastic modern buildings. I live on the edge of the city and I’m very close to a 12th century church with a lump of steel and glass sticking out of it a thousand feet high. But there’s still a massive amount of Victorian buildings, because that was our period, and I think a lot of our literature and our attitude is defined by that.

I was brought up by the last of the Edwardians, and they were brought up by Victorians, so although I don’t identify individually with those people, I know that that’s where we come from and it does appeal to me. But people also accuse me of being an everyman as well. I’ve been typecast in about 17 different modes!

Do the roles ever seep into your personal life? I’ve heard the story about you going into a pub during the filming of Mr. Turner and saying to the barman, “Are you a provider of wine?”

That’s actually a misquote: I said, ‘Are you a purveyor of wine?’ That happened right at the centre of still trying to create and come up with Turner’s essence, and he was with me all the time, and I still haven’t quite shaken off the experience of that. I learned to paint for two years as well, before I even started rehearsing. I’m sitting under a copy I did of one his paintings and I look at now and think, how did I ever do that? There’s nothing like the knowledge of being hanged in the morning to concentrate the mind wonderfully. When you work with Mike Leigh you have to come up with the material yourself and research it. It was the only time in my life when the barriers between me and the character eroded a little bit. Even though Mike is very strict about ring-fencing you and the character separately, I found myself wandering the streets of London and you start talking in this bizarre early-Victorian speech. I remember thinking, Oh fuck, I have to pull back from this and I had to go home and calm myself down. I remember once being asked when my wife was with me, ‘does Tim ever bring his characters home?’ I said, ‘Absolutely not,’ and at exactly the same time, she said, ‘Of course he does.’

In The Enfield Haunting you played Maurice Grosse. Did you ever get the heebie-jeebies during filming?

I got them seriously before I did it. I read it and I felt very frightened because I am easily spooked. I actually turned it down as it freaked me out too much. It wasn’t long after doing Turner and I was very very tired. Then the producer said, ‘I’m sorry, we can’t accept that. Please ask Tim to read it again.’ And then I was reading it again and I had a sort of epiphany. I thought, as scary as it is, and as open as I am about ghosts, nothing can exist in the afterlife worse than what’s going on in the present. People being slaughtered in Syria, constant starvation… I thought, why on earth am I worrying about dead people? It’s the living that are most terrifying. What I loved about the Enfield Haunting was it was a journey about emotion, it wasn’t just a scare-you. It’s about a man who’s lost a child himself and was trying to find some solace in that. Maurice Grosse was a very dignified, ordinary kind of guy. It was interesting to investigate whether it was this child’s disturbed childhood and this man’s desire to summon up a ghost that made it happen, and is that what makes ghosts happen anyway? It’s like if you want God to be there, God is there. You don’t want him to be there, and he ain’t!

Was that your view on ghosts before you made the series? That they are the product purely of imagination?

No, I’m still not sure. Don’t forget that 22 years ago I had a life-threatening disease. I had to go very deep down into areas where I had to think about these things. Certain things happened; I was given signs and though I didn’t get any visitations, but, you know, there are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy, Horatio. Look, if you can record your voice or a song, or take a photograph with an instrument and it can be there forever, why can’t a room, for instance, capture an event that might be there for evermore? What is about a certain room that everybody feels? What is that? You can walk into an ancient house and think, this is lovely, or you can walk into somewhere like that semi-detached in the Enfield Haunting, built in 1936 and think, Oh Jesus, what’s going on here? Is it a trick of the light, is it the lie of the land, the tilt of the horizon? As you get older you realise that so many things we do are driven by the subconscious anyway.

In other words, the person walking into that room is bringing and extra something for the room to provide. And it might not even be the room itself; it might be in the earth upon which the house was built.

Exactly. Where I live, just around the corner there’s a thousand people buried under there from the plague. Without getting too spiritual about, it who’s to say that these things aren’t recorded somewhere, even if it’s in a wisp of air that’s gone all the way around the earth a thousand times, for a thousand years. When you hear someone like Dr. Brian Cox saying that in every living human being and every single thing on Earth there’s a tiny morsel that was in the Big Bang. And we think ghosts don’t exist?

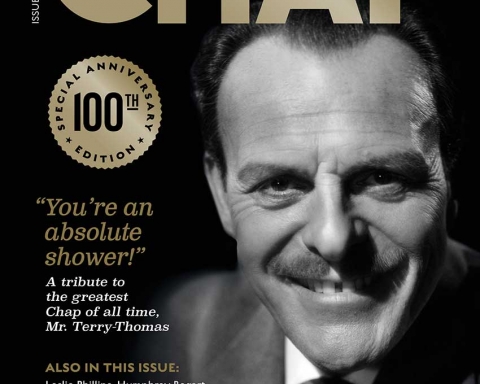

Did you ever meet Terry-Thomas?

No, but I would love to have done. I did work with Dickie Briars, who was related to Terry-Thomas, and sometimes I could see in him [does perfect impression of Terry-Thomas] “I say, you absolute cad!” He started in the music hall, didn’t he, and became a great character. His performance in School for Scoundrels is just wonderful, and It’s a mda Mad Mad World… [Terry-Thomas voice] “You Americans are obsessed with women’s bosoms, what’s the matter with you?”

Do you think he was playing a caricature of himself in real life? He forced it a bit at the beginning of his career and then it became real?

I’m not sure, I don’t know where he was brought up.

He was brought up in North London, the son of a market trader. Lower middle-class background, nothing in his past indicated a career in film or a swaggering dandy.

It’s often surprising when you find out where people with these posh accents come from. Derek Jacobi is from Leytonstone or somewhere like that. I remember reading a very touching interview with Terry-Thomas when he was very ill with Parkinson’s, and saying [Terry-Thomas voice] “The only part of me that doesn’t shake is my earholes.” So maybe people do end up becoming what they’re portraying, if they can keep it up, or sometimes you don’t know what they’re like at home.

When we interviewed Richard Briers, he said that at some point in his youth, Terry-Thomas, as a family member, suddenly started calling him ‘Ricardo’ and he never went back to calling him Richard or how he used to speak.

But there’s a kind of poetry in that, isn’t there? It’s more than just an affectation, that’s a poetic take on a persona. You could say it’s somebody pretending, but then again it’s somebody finding something that’s an expression of something they couldn’t express in another way. The classic example of that was Quentin Crisp, who unashamedly said he was a construct, like a sort of performance art. It’s what you feel makes you comfortable. Like this guy who’s just been exposed as an Italian New Yorker who was a royal commentator. He’s called something like Jimmy Crathenden-Smithers or something, but his real name is Tony Mancini or something. He’s been on television commentating on royal weddings, purporting to be an aristocrat, while he’s actually from upstate New York. Is he a liar, or is he just getting in touch with something he feels he is? It’s all an illusion. As a character actor you’ve got a mild form of an undiagnosed multi-personality disorder, but at least you get to exercise that in a safe place. As scary as I find it, I think I’d be deeply unhappy if I couldn’t do it.

Interview by Gustav Temple

Pre-order on Amazon