Gustav Temple and Olly Smith on the transformation of gin from slum-dweller’s slosh to sophisticate’s tipple

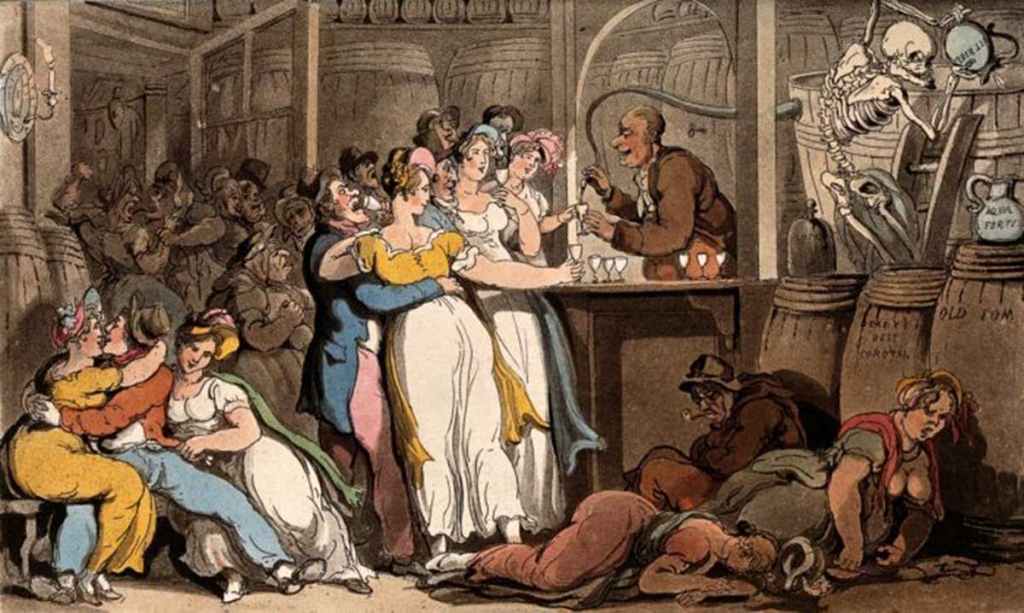

“Liquid Madness sold at tenpence the quarter.” Thus did Thomas Carlyle, admittedly not the world’s greatest party animal, describe gin in 1839. Back then, gin was still waiting for its launch into the High Life, and was the tipple of choice for the lower orders of London for at least a century. Gin palaces, glamorous as they sound, were disgusting dives in seedy quarters of the capital where the bottom end of society would spend the evening quaffing crude early forms of Old Tom gin, before sloping off to some hovel or simply bedding down on the floor of the tavern. Some inns had a piece of rope strung before the bar, where patrons could topple into slumber and await their hangovers to grab them at dawn. Others took advantage of the tavern’s generous offer: “Drunk for a penny, dead drunk for tuppence, clean straw for nothing.” Some of these once dreadful establishments survive to this day, though the gins they serve there now are vast improvements on Old Tom.

The origins of the production of gin go back even further than the days when you could spend the night on the floor of your local hostelry. Gin was invented by a Dutchman named Franciscus de la Boe, also known as Dr. Sylvius, who was experimenting with cures for kidney complaints by infusing raw alcohol with juniper, known for its therapeutic properties. He named it Genievre, French for juniper, and it proved an instant success – not surprising since anything with a flavour would have been an improvement on the raw alcohol generally consumed in those days.

Gin is quite unique, compared to all other spirits, in that the principal flavour, which comes from juniper berries, alongside other botanicals such as coriander and angelica root, as well as a few “secret” ingredients, depending on the manufacturer, are all fused with a spirit that has already been distilled – basically a vodka. This is unlike the flavours of whisky, brandy, rum and the like, all of which are informed by the base grain, grapes or sugar cane from which they are distilled and created.

Once gin hit our thirsty shores, brought from Holland as duty free gifts for their families by soldiers, it immediately tickled the palates of the poor and didn’t leave that stratum of society for 200 years. One of the causes was the introduction of new taxes by William of Orange on the import of French cognac. For some reason he excluded grain-based spirits such as gin, which resulted in a tidal surge of gin pouring into Britain. By the late 17th century, anyone wishing to set up a gin distillery could do so simply by posting a notice to the public ten days before going into production. This led to the dark days of gin, when any old rubbish, including oil of vitriol and turpentine, was hurled into the stills instead of quality spirit and expensive juniper berries. Such was the addiction of the masses to any and every form of gin, that any attempts by the authorities to curb production were met with rioting in the streets. It was not until the Tippling Act of 1751 that quality control began to ensure that licenced victuallers provided their customers with gin that might not kill them immediately.

London Gin, a blend with a unique sense of origin thanks to its fresh bright style, came to exist in part due to the wonderful natural springs the city boasts, principally at Clerkenwell and Goswell. Not so important today, but back then the purity of the water had a large effect on the quality of the gin, which gradually improved over time, eventually coming to the attention of the upper classes, and particularly the bon ton of the Regency, always on the lookout for new ways to get utterly plastered. Lord Byron himself once declared that “Gin and water is the source of all my inspiration.” But then Gordon (no relation to the gin) was always trying to be outrageous and may have been exaggerating.

Gin is as wide and wild as the cast of a Dickens novel, in that it can be wrought from pretty much any neutral spirit from a vast range of base agricultural products from sugar beet, grain, apples, molasses and more. The fire in gin comes from the pure spirit, the hidden spark that ignites the fireworks of flavour imparted to via botanicals, the most important of which is juniper. Juniper gives gin its buzz thanks to its electrifying natural freshness. Other aromatic botanicals vary from gin to gin, but commonly include angelica, cardamom, coriander, citrus peel and more are either macerated in the neutral spirit before a further distillation or they are suspended during a further distillation to be infused into the vapour. What we predominantly enjoy in the Greatest of Britains is called London Dry, which is a bright and zesty style of gin that deploys a superior system of distillation than cold compound gins that are cheap and best avoided using oils instead of raw ingredients for flavour. In recent years there has been an explosion of new innovative distilleries crafting gin across our shores. Among the finest in our opinion include:

Warner Edwards Harrington Dry Gin

Created by lifelong buddies Tom Warner and Sion Edwards in Harrington, Northamptonshire. With a fragrant dose of cardamom, this was the gin that resulted in the commencement of formal dancing at Olly’s 40th birthday celebrations. It is more or less irresistible as an all-round top-notch gin.

Sacred Gin

Their London Dry Gin is a double gold medal winner forged in a craft distillery hiding in Highgate that began its life in a Wendy house. Microdistiller Ian Hart is a magician of reduced pressure distillation – under a vacuum – which gives his unique gin extraordinary purity and freshness. The distillery takes its names from one of the botanicals in the gin, Boswellia sacra, also known as Frankincense. We love it served neat from the freezer.

Gin Mare

From the shores of Barcelona comes this outrageously delicious Mediterranean gin, enriched with savoury finesse from curious botanicals such as basil, thyme, rosemary and olives. In a gin and tonic served with Fever Tree tonic, we reckon it turns a moment into a meditation on the sheer splendour of fine flavour.

Xoriguer

From Mahon in Menorca, this gin is fabulous value and is also, alongside Plymouth, one of the few gins of the world to have a geographical indication – Gin de Menorca. Kicking off with the British occupation in the 18th century, it’s made in wood-fired pot stills from distilled wine and spends some time in American oak before bottling. The locals take it as a ‘Pomada’ in a tall glass packed with ice topped up with real lemonade and a slice of lemon which tends to unleash the hidden fiesta inside us all.

Williams Chase Elegant Gin

Clever kit that deploys apples to create a very fine base spirit on their Herefordshire farm in a carter-head still called ‘Ginny’, which Olly has in fact met. One part Martini to two parts Williams Chase Elegant Gin shaken over ice served in a cold martini glass with a slice of apples is, as Ollie Reed might have said “marvellous as the thunder of happiness”.

Read more Olly Smith on drink in Chap Summer 20, out now