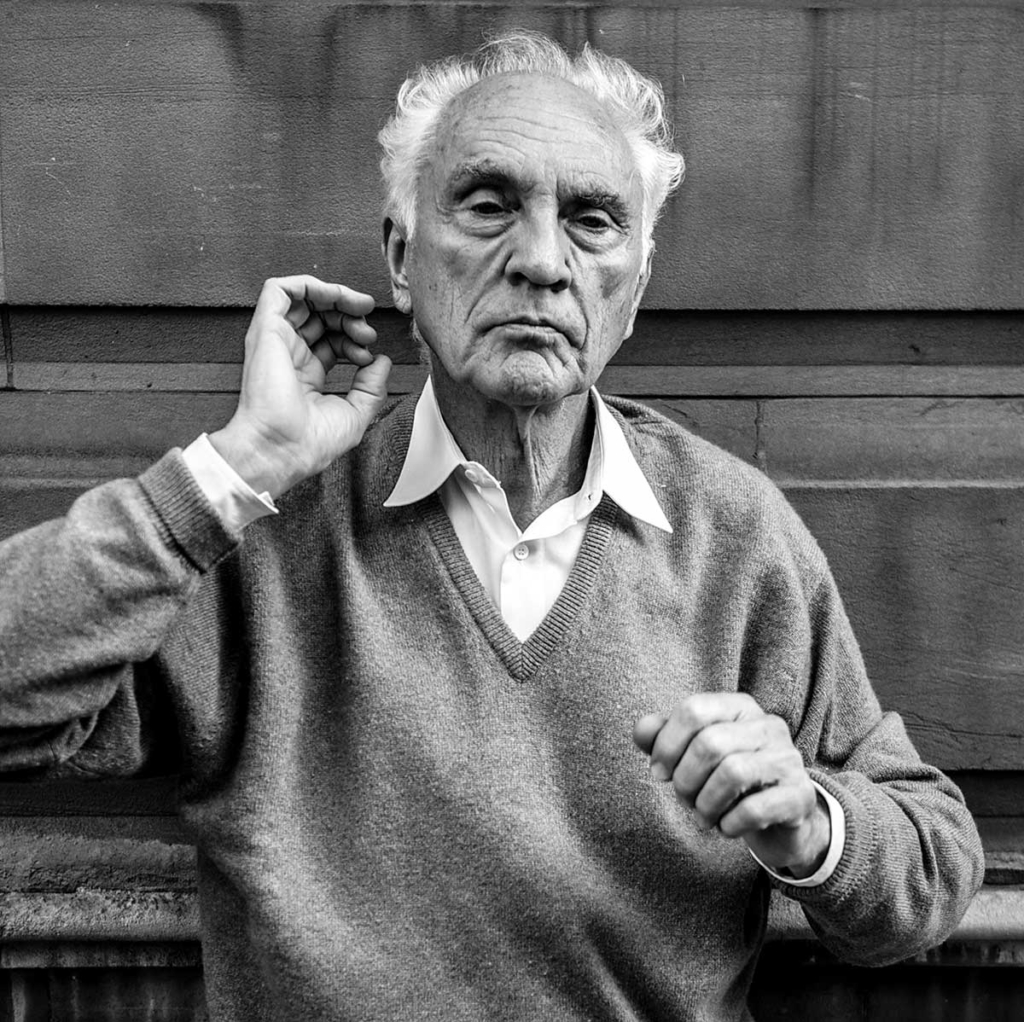

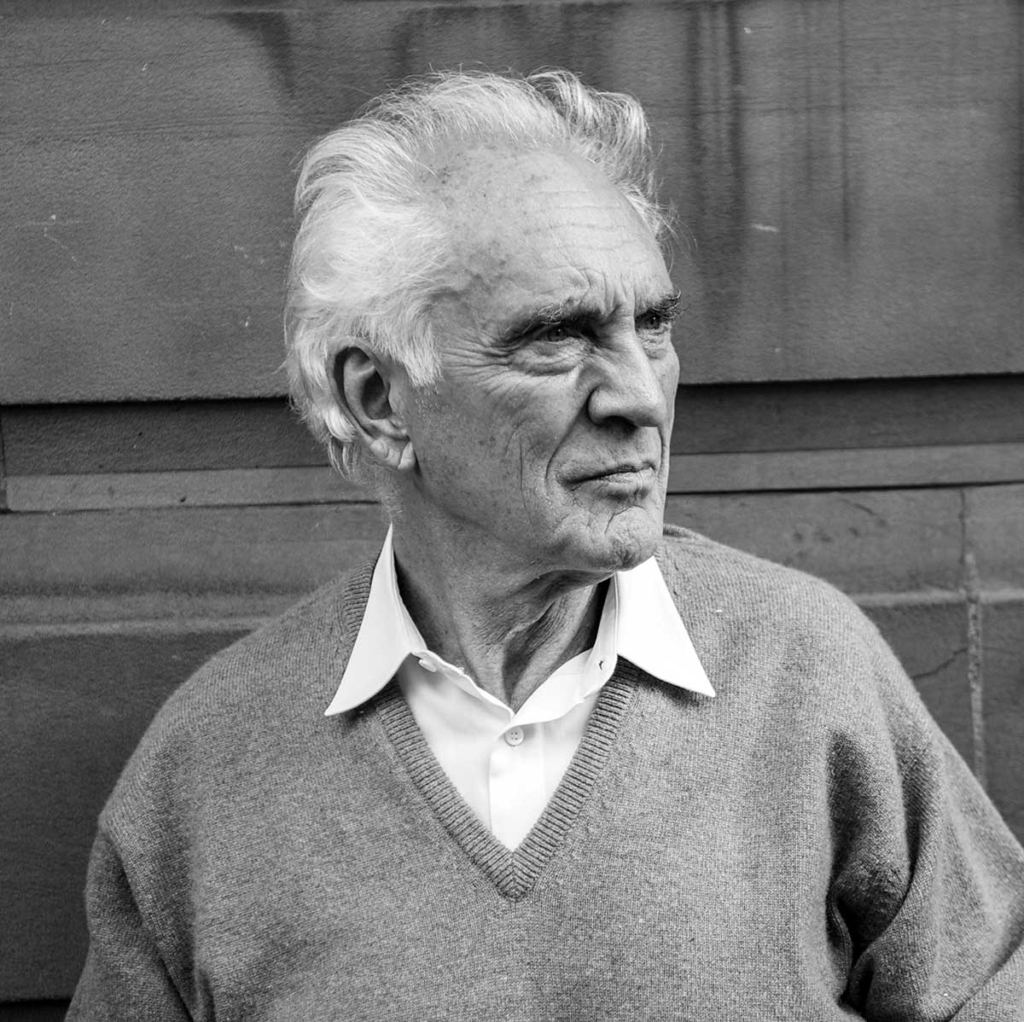

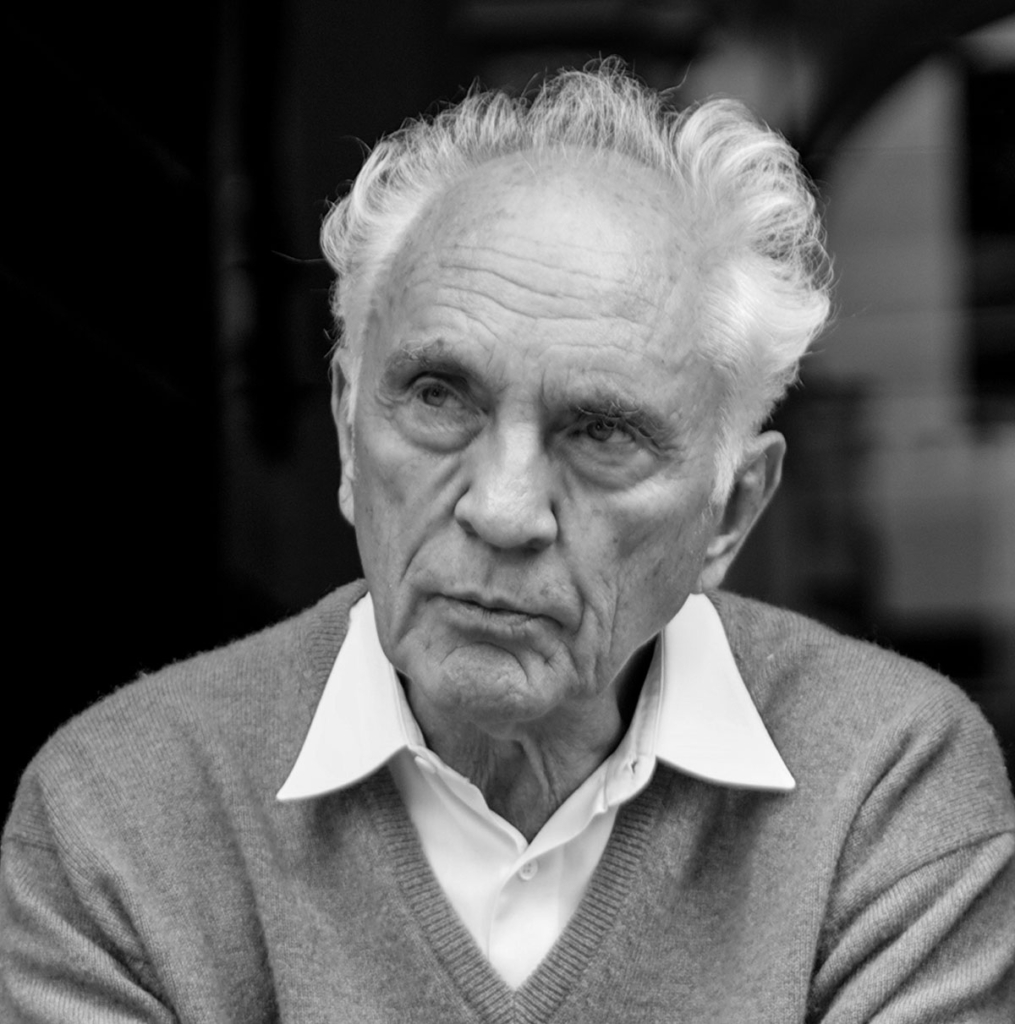

An encounter with the sixties icon in 2014, republished following the sad passing of Terence Stamp on 17th August 2025. Photos by Peter Clark.

“Terry meets Julie, Waterloo Station, every Friday night.” Apparently you are Terry, from Waterloo Sunset by the Kinks, and Julie is Julie Christie?

There are two stories, and either way Ray Davies is telling porkies. My brother Chris, who changed his cosmic address about a year ago, discovered people like the Who, and Hendrix was on his label. He was friendly with Ray Davies, and he told me, back in 68 or 70 or whenever it was, that Ray had told him that he was visualising Julie and me when he wrote that lyric. Now recently, Ray Davies has denied that, so either he was telling porkies then, or he’s telling porkies now. But I stand by what my brother, who I adore, told me, and I don’t know Ray Davies.

Did you ever actually meet Julie Christie at Waterloo Station?

No, but I met her at lots of other places!

Many of your biggest film roles have been extra-terrestrial or mythical characters. Have you ever fancied playing a man called Frank who works in a stationer’s shop?

The extra terrestrial ones are the ones that have been successful. I haven’t been in many big box office movies, but the ones I’ve been in were really big; things like Superman. But then I’ve done a lot of serious movies… I wanted to do things I felt I could really cope with. My first two films set the mould; I made Billy Budd, then I was asked by William Wilder to make The Collector, which is the first serial killer movie. So that set the trend for me, so I then bounced between those extremes. But I have done lots of very ordinary things. The thing I did recently with Vanessa called Song for Marion was probably the best thing I’ve ever done.

What was your first encounter with the world of cinema?

My mother introduced me to the movies. When a Gary Cooper movie came on at the pictures, she took me with her. The first movie I ever saw was Beau Geste and I wanted to be him. I didn’t realise he was an actor, I just wanted to be him. Then, when I was about 14, knowing that it was unlikely that somebody like myself could ever become like him, but I continued going to the movies, and I saw a movie called the Razor’s Edge, with Gene Tierney and Tyrone Power. A lot of things happened during that movie because it was Somerset Maugham’s experience in India with a great sage called Ramana Maharshi, and Maugham wrote himself into the story and was played in the film by a great actor called Herbert Marshall.

When we got our first TV I was about 16 or 17, and I started saying things like, ‘I could do better than that.’ My dad said, ‘People like us don’t do things like that. Son, I don’t want you to talk about it any more.’ My dad was what I think of as a real alpha male. So what happened was that all of my mates went into the army to do their two years, and I just missed that. So I thought, I’ve got two years that nobody else has got, so I can try something and fail. But because I couldn’t go against my dad, I had to leave home. So that’s when I left the East End and I moved up to Harley Street with a kid from East Ham called David Baxter, who was much more advanced than me, he was like a Bohemian. We got a basement at 64 Harley Street. As soon as I got up West, I started auditioning for drama schools.

You worked with both Pasolini and Fellini. How were the great Italian arthouse giants to work with?

I worked with Fellini first, and my life changed radically while working with him in Rome. He introduced me to the first sage I’d ever met. At the time, I thought sage was what went in the turkey at Christmas. But although at the time it felt as though the shift was moving one or two degrees, as the years passed, instead of winding up in Scotland I wound up in Iceland. After that, Sylvana Mangano suggested me to Pasolini, so my great experience on Teorema was working with her more than working with him. Pasolini was wonderful but he just let me get on with it, which I prefer a lot of the time.

You shared a flat with Michael Caine in the sixties. How did that come about?

In my first year at Webber Douglas Academy, a great agent called Jimmy Fraser from Fraser Dunlop came to see me playing Iago, and he took me out for a drink afterwards, and he said, how is it? And I said it’s tough; I was existing on nothing. I was getting 20 quid a month, and that was my rent. And he said, if you want to leave, I can get you work. So I left and he did get me work.

I was in a play called the Long and the Short and the Tall. Michael Caine had been the understudy for Peter O’Toole in the West End production and he’d never got on. So when the play finished, they offered Caine the lead when it went on tour. Then they lost dates and had to recast, because all the other actors had got other jobs, except Michael. And they said, who else knows the words, and they said there was this kid at Richmond who played the wireless operator, and that was me. So that was my second job, and I fell under the influence of the great Maurice Joseph Micklewhite, otherwise known as Michael Caine. I learned a lot from him about chutzpah.

When that tour finished he came and stayed with me. I’d moved from the basement to the penthouse of 64 and I needed a lot of guys to help me pay the rent. Then Michael said, look these are not actors, why don’t we get a place of our own. And during that time I got the play Why the Chicken? by John McGrath, and that was the play that Ustinov came to see me in when he was casting Billy Budd.

Are you still in touch?

As soon as he made it, he didn’t need me in his life any more. I think he was concerned, and now I understand more, like why would he be sharing with a younger good-looking guy? I was incredibly sad, because he’d become my best mate. But I haven’t seen him at all since then. He was six or seven years older and he was my first real guru. He hadn’t had any huge success but he knew the business and he was teaching me the basics of it. But to give Michael his due, he was just being realistic. He understood that people would say why are you sharing with that guy.

But it didn’t come up like that. I called him when I was in California making The Collector, and it was his turn to find us a place. “Don’t worry, I’ve got somewhere, it’s great,” he said. And when I came back, with Jean Shrimpton, who I’d just met while making the film, the flat was wonderful, it was in Albion Mews. And I couldn’t believe it – he’d put us in the box room and was treating it like his own place. So Jean and I moved out immediately.

And could Michael make a good omelette, as he does in The Ipcress File?

Michael was a good cook.

Which of your films would you most like to be remembered for?

I think my first movie, Billy Budd, my first Hollywood movie, The Collector, and the last movie I made with Vanessa Redgrave, Song for Marion, because they were the most challenging.

What do you think of Abercrombie & Fitch opening a children’s store on Savile Row?

I lived in Albany for 35 years and I am shocked at the St James’s village of today. It’s not that I’m disapproving, it’s just 99 per cent different. All the years I lived at Albany it was a village, with little cheese shops, little shirt shops; I knew all the tailors, I went to George Cleverly, who made button-up boots for Valentino, and he was in Bond Street in a basement. So that was the St James’s of my era and it’s all gone, but it doesn’t really surprise me. Some of the tailors are still where they always were, but the place itself doesn’t have that exclusivity any more. My niece is married to Ben Stoppard, Tom Stoppard’s son, and he wanted me to go with him to Anderson & Sheppard for his first fitting. It was like going home, because the shop hasn’t changed and all the guys still remembered me. So there are little pools of how it used to be, but you have to know where they are.

Has anyone ever influenced you sartorially?

I didn’t need any influence, I came in with it. My mother told me that when she was buying me my first suit, I could only have been four or five, she was out shopping with me all day because nothing we saw was right. Finally we went to a shop called Leech’s and I found a Donegal tweed suit. But how did that happen? Nobody taught me.

Before I made money my shoes never fitted me, because it never occurred to me that my right foot was bigger than my left. But when I made some money, I found George Cleverly and got shoes that were comfortable and made to measure. Even before I met George I always dressed from the feet up, and whenever I see men, I always look at the feet first. You can tell everything about a man from his shoes.

Doug Hayward really influenced me, he was a great tailor. But it was my friend Frederik Pallandt, from Nina & Frederik, who said everything about my life was too cluttered. He made me break down everything into groups of five, then choose one and give the other four away or sell them. I would have been about 28 and I thought I was the finished product; I had an incredible vanity about how I looked.

Who would you say had the biggest effect on your acting style?

Antony Newley. When I met him for the first time, Lionel Bart introduced me to him while he was in the middle of composing Stop the World, I Want to Get Off. And he played and sang for us all the songs. He hardly noticed we were there, and when Lionel said, “This is Terence, he starts work next week on his first movie,” Newley realised how much it meant to me to meet him. He looked at me as if to say, “You’ve got my attention.”

I said, “What to do?” and he replied, “If in doubt, do nothing.” And that was how I nailed the part at the end of Billy Budd. I spent the whole film trying to imagine how I can act ultimate peace, and I failed, so I’ll just have to do what Anthony said. I remember getting up there on the boat, and the noose was waving in front of me, and I was just kind of empty. They put the noose around my neck and the other men are all mutineering because of the injustice of it. But it’s the look on my face that quietens them, and that was the thing I hadn’t been able to fathom.

Into my head came this little song, and it was so silly that I kept trying to push it out. Then in a moment of insight, I realised it was a song my granny Kate used to sing to me after I’d just passed the 11+, and I’d take my homework to her house in Barking Road. She’d sit me in front of the stove and she’d go in the kitchen and make me a marmalade sandwich, and she would sing: “Little dolly daydream, pride of Idaho, so now you know, and when ye go…”

That came back to me and I just looked at the guys, then Ustinov said, “Cut!” From then on in, that was my acting. I did everything I could to prepare for each role, but I knew that it was all about the space.

RIP Terence Stamp, 22nd July 1938-17th August 2025