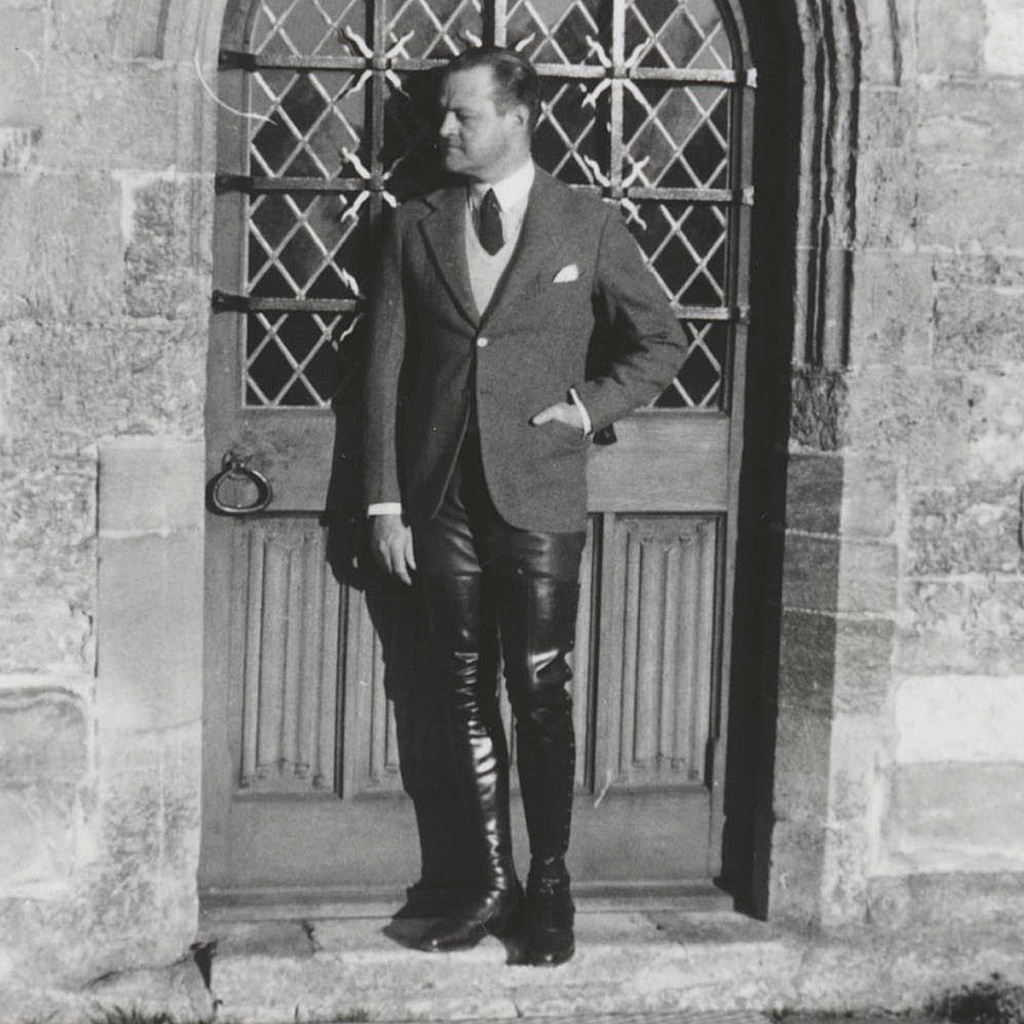

Henry Cockburn pays a visit to Lord Fairhaven’s enormous sartorial collection at Anglesey Abbey.

© National Trust Images

Anglesey Abbey only plays at being a National Trust property. In truth, it is something far stranger. Legion are those obstinate houses, prized from the brittle, mummified grip of thoroughbred Normans so that we, thermos-bearing Saxon–Socialists may poke and pry and gawp.

But not here. Unlike its faded cousins, Anglesey was offered up, entire and intact, by a man at the height of his powers. Here, one does not chart the decline of the great house. Here, one does not feel the weight of history. I step through the door at Anglesey and I step into a manicured 1930s stage set and the presence of one man: the enigmatic Lord Fairhaven.

Fairhaven’s wealth – derived from American ancestor and Rockefeller rival Henry Huttleston Rogers – was secure. He had relatives aplenty and any tax bill could have been covered three times over. No, Anglesey was left to the National Trust on one rigorous condition: that the house and its collection never be altered. This is no museum. It is a hunkered mausoleum. A quiet shrine to beauty. The Taj Mahal as reimagined by Noël Coward.

And if you are wondering whether a man as fastidious and self-canonising in his collecting habits would extend those traits to his wardrobe, wonder no more. Welcome to ‘Tailoring an Image’, a heartlessly rare and cruelly fleeting menswear exhibition. My favourite room – Fairhaven’s wardrobe – has been unpacked, mannequined, and now his suits stalk the halls in which they once breathed. A dozen headless Fairhavens, ready for whatever life throws at a golden-age country squire.

I begin in an oak-bound room and there he is, hovering in red velvet by the concealed bar in the panelling. Whisky decanted. Cigar soon to be lit. I have always felt his presence here but this – beneath one of his many chin-led portraits – borders on necromancy. The suit itself, a two-piece by Huntsman, was first ordered as a smoking jacket, a charming note in their ledgers suggesting that he might be minded to order the trousers later. Reader, he did.

© National Trust Images/Mike Selby

It is in immaculate condition except for the buttonhole, which grins fixedly from the force of a hundred white carnations. A buttonhole on evening wear? A two-piece smoking suit? You would be forgiven for thinking we’re dealing with a dandy here, but that’s not the impression. The maverick elements do not feel like affectation or flamboyance, rather like intimate self-knowledge. He aims to impress no-one but himself. Indeed, as a recording of his maid tells us, ‘Lordy’ (as his staff called him) always dressed to dine, even when alone, and had carnations delivered to his room every morning – as many as five or six for his planned changes of outfit.

Certain makers were clearly favourites: Huntsman for tailoring, Bates for hats, Maxwell for footwear – all of which still operate today. Indeed, Huntsman has supplied fascinating insight into the collection, delving into their own hallowed annals to reveal individual cutters and sewers who worked on the garments themselves. The initials C.H. on one label, for example, belong to Colin Hammick, Huntsman’s head cutter in the 1960s who not only dressed Gregory Peck and Brian Epstein, but was himself voted 1971’s ‘Best-Dressed Man of the Year’ by Tailor & Cutter magazine.

© National Trust Images/Leah Band

The jewel in the collection is Lordy’s cropped red leather breeches. I say jewel, but really it’s a hoard. He owned sixteen pairs, one in every colour of the rainbow. No sheep, goat, or buck was safe from being whipped up into a snug pair of shorts when Fairhaven was about. If the Trust thought they could divert the wrong sort of attention by squirrelling away the other fifteen pairs, they were wrong – here I stand.

These mid-thigh wonders, originally miscategorised as lederhosen (the fens are much too flat for yodelling) were unique to Fairhaven. He wore them with thigh-high gaiters, whether riding or rambling for an – ahem – striking silhouette. Again through the Huntsman archives we learn that these were sewn by ‘Sybil’, a small, frail-looking lady who made their breeches for sixty years. Each stitch had to be pushed through the thick leather individually, resulting in the not-quite-even lines that mark out the truly hand made.

© National Trust Images/Mike Selby

In highlighting the quirky and the unique, however, we lose what is most remarkable about this collection: that it is, essentially, complete. Menswear suffers from being very pass-downable. Very split-uppable. Very wear-throughable. To see a man’s wardrobe in this condition ‘in the round’ and frozen in time is, to my knowledge, unparalleled. If I have one criticism of the exhibition it is along these lines: I want more. I want every one of those fifty suits lined up. I want a kaleidoscope of socks, a tweed carousel, a leather cavalcade. This, however, is the critique of the enthusiast, nay obsessive.

In my opinion, ‘Tailoring an Image’ should not be a special exhibition at all – it should be how the house is always seen. When all this is packed away come November, Lordy’s spirit, in a sense, will be packed away with it. The house will miss him, and his leather britches.

On my way through, I mention to a guide that I think Fairhaven would quite enjoy his togs being on display. ‘Yes,’ he says after thinking for a moment, ‘but he’d hate all these people peering at them.’ An image flickers in my mind, of a man in a dinner suit – carnation so crisp it might still be on the stem – dining alone in the echoing heart of a long dead abbey.

Tailoring an Image is at Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire, until 31st October 2025