Hercule Poirot is an iconic character. What was it that drew you to the role and why did you want to play him?

In this case it was the three scripts that Sarah Phelps wrote. I thought that they were very well written, the character was interesting, Hercule Poirot was perhaps not very happy and in a phase of his life that we don’t see very often and isn’t dramatized very often and that is what interested me.

Sarah Phelps always brings something new to Christie’s work. When you were reading the script what were the things that really popped out and appealed to you?

Well as I said, where Hercule Poirot is in his life; he is nearing the end of his life, he is quite forgotten. As it happens he has lived in England for almost two decades and the world has passed him by. Apart from the plot, which I think is very well plotted, and a lot of very good characters, that was the part that interested me the most.

Can you tell us a little bit about Hercule Poirot? Where do we meet him in the story and how does his story progress?

Hercule is receiving letters and he puts together that these letters are being sent to him by a murderer who is called ABC. This murderer is going through the alphabet and murdering people whose names have double initials. That’s where he is at the very beginning. He’s starting to sell some of his possessions to get by (he says he has savings but he doesn’t) and he’s, like I think many people do, in the process of fading away. Then he tries to involve the police. His friend inspector Japp is no longer there, Hercule didn’t even know he’d retired, and he finds it very hard to acquaint himself with the new inspector that he has to deal with. That’s where the story starts.

That new inspector is Inspector Crome, played by Rupert Grint. Please can you tell us a bit about the relationship between Hercule and Crome?

I don’t think their relationship starts in a very promising way but they eventually gain a measure of respect for each other through the course of this story. Poirot is someone who is very experienced and Crome, Rupert’s character, is decidedly less; they have an interesting relationship.

You share a lot of scenes with Rupert Grint. How has it been working with him?

It’s been very good. He has a lot of charm. He has a way of being sort of funny and off-centre without trying very hard. He brings an inner turmoil to the funny things he does that I always think is absolutely necessary actually to be funny. The rest is maybe witty but not really funny.

What was it that you felt about Hercule Poirot that you really wanted to bring out in your performance? Was there anything in particular that you wanted to develop in the character that we know so well?

I am certainly no expert on Agatha Christie, and in my experience, a lot of times when you know a piece really well, a piece of literature that it’s based on, it just brings trouble. So, I think that first of all it’s really Sarah Phelps’ choice to decide what to emphasise or not emphasise. One of the things that I thought was important was that Poirot was someone who had lived here in England for nearly 20 years when our story starts. I thought that was important on a number of levels. He says at one point that he’s lived here for 19 years and people still think he’s French. The first thing is that he isn’t French but he has had a long experience in England, in a way about a third of his life, and I think that is an important factor and has to be played and made clear and understood which I think is a difference from how this story normally is told.

I don’t know if Agatha Christie has the same sort of reputation in America – although she sells all around the world – but is she an author that you were aware of?

Of course, Agatha Christie has a reputation everywhere. I am sure I read two or three Agatha Christie books when I was a kid but it would have been when I was pretty young. Although I don’t know how those shows did in America [And Then There Were None, The Witness for the Prosecution] but I thought they were just excellent; they had terrific cast; they looked lovely, very well written and very, very good. But of course she is known around the world.

In terms of the filming, have there been any particular highlights so far? Have you enjoyed filming on location in the UK; has there been a good atmosphere on set?

Newby Hall is a lovely place and it was insane to be on the old trains, boy they put out a lot of dirt, good Lord! But it’s gone very well, I hope. I think it’s a good cast, some of whom their work I knew, or at least a tiny bit, and many whose work I didn’t know, but I think Alex has gathered together a very good group and I’ve very much enjoyed it.

The 1930s is a very interesting period. Have you done much work set in that period?

The 1930s is not a period I have done a lot of work in but I’ve certainly read a lot about it. I’m probably more familiar with the later 30s, the Second World War and after, and the First World War in Europe proper and also in the UK, but not so much in the early 30s. I would be reticent to speak about it but certainly everybody, myself included, has felt exile; has felt an outsider; has felt unwelcome in various places and situations. I think Sarah draws interesting parallels with today. I don’t think it’s easy to be an immigrant. I don’t think it’s easy to leave what you know and strike out for a new existence. In Poirot’s case, he has established something and been invited everywhere important and chic and to various stately homes to do his murder mystery evenings, and then the invitations stop, as they invariably do in life, and I think Sarah explores this delicately.

It’s a painful portrait of a man.

I hope it’s painful. I remember once I was doing a play here [in the UK] in the early 1990s, it was fairly late but my little girl was not sleepy at all and something came on the TV. It was a film about two elderly people who were retiring, I think Stephen Frears directed it, and I thought it was just a wonderful thing. I thought it was terrific. My little girl, who was tiny really, stayed up and watched it. It did a great job of just watching people fade away. But that’s life, we all see it with our grandparents and then our parents, and then it’s our turn and that’s just normal. But, it doesn’t make it any less painful and you don’t see it very much [on screen]. I don’t know… It often seems we produce a million films that are all about teenagers.

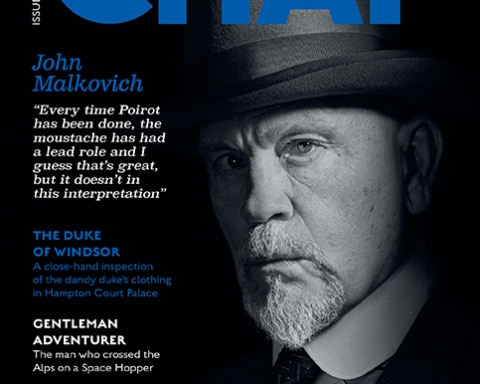

What did you want to achieve with the very famous look?

I didn’t really have an opinion about it. I was doing some work in Chicago back in April when I had the first conversation with Alex [Gabassi]. From what I understood from Sarah’s script I thought that I would need to get a wig and I don’t think that my moustache would necessarily grow that way but anyway, we started to conceptualise and gather the elements to fulfil that vision which seemed to me to describe someone with very, very dyed hair and a very, very dyed moustache. I thought it was part of the pathos. I could see that it could be one that wasn’t irreplaceable but I understood it as a short hand. Alex said actually no, I want you to look like you look now, I saw a picture of you yesterday and I want you to look like that. To me that’s a decision for a director. The director is the lead interpreter of something that includes what is the text? what is the story? how do you tell it? what does it look like? and probably principal among those is what are people actually seeing? My feeling was that a million people play Hamlet and they don’t all look alike; a million people play Richard III and they don’t all look alike. Obviously, you want to do something that doesn’t disrupt the notion of what period it is. I think every time Poirot has been done, the moustache has had a lead role and I guess that’s great, but you know it doesn’t in this interpretation really, and I think that’s fine.

You have mentioned conversations with Alex Gabassi a number of times. What is his style? How have you found working with him?

I think Alex is very smart and he’s got a very good sense of humour. I love to watch him move things around on the set because after a day or two I thought, my goodness, you are even crazier than I am! I am only 88% as crazy as him. Everything he’ll organise and reframe, which, by the way, I like; I mean the form is founded upon manipulating images. I think he is very smart, very good with the actors. I feel plenty of freedom but at the same time I like to hear ‘I want one this way’ or ‘try it like this’ etc. That’s the whole point. I like to have direction from a director. I always welcome that very much and I always try to give options that he may like and that maybe wouldn’t have come to mind. So for me it’s a very happy collaboration.

Throughout this process, are there any particular words that resonate or have resonated through this? Is there a word that you have repeatedly felt, or something in the script, that sums up the feeling that’s going on around this time?

Not really, not in a word. I think he has a, and I don’t even know what we call it, it’s not really the right word, but I think we say detachment, a kind of recul, sort of… he’s reflective. That’s the time of his life I think, and he’s always reflective about people and what they can get up to. Sarah’s screenplay has interesting notions about Poirot’s past, which I think are very important. But I don’t know, maybe I would say reserve.

What drives Hercule Poirot? When he sees these victims, they’re not just dead bodies to him, it’s almost a very personal thing – beyond the fact that the killer is writing to him. What is driving him through this story?

It’s the same thing that drives us all: his past. Scott Spencer had a great line in his novel Endless Love: “the past rests breathing faintly in the darkness, it no longer holds me as it used to, now I must reach back to touch it”. I think in Poirot’s case that is what motivates him. I think Sarah has had the most interesting take on what that past was and why it dictates his present and future.

There are some pretty brutal murders and a race against time. Is Poirot scared or is he convinced that he’s going to solve this case?

I think there is being convinced you are going to solve the case and then being convinced that you have to solve the case. I’d maybe say that he is convinced that he has to solve the case, with the associates who help him, Crome [Rupert Grint] being one of them. I think he’s worried. I don’t think he’s personally afraid but he’s afraid that he won’t have done enough, wont have been on the mark enough or clever enough to discover who is committing these heinous acts. So I think he has fear in that way.

Is this Poirot’s last chance saloon?

Well, one never knows that in this life. But it certainly could be.

Interview by Gustav Temple

John Malkovich, it goes without saying is a great actor. Thank you for this timely interview. Yes, I did watch The ABC Murders and this interview gave some insights about the series which I highly recommend.