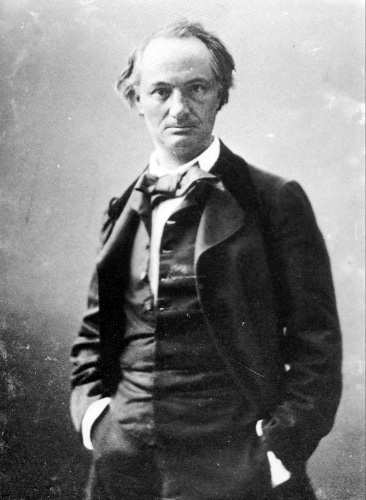

“The crowd is his domain, as the air is that of the bird or the sea of the fish. His passion and his creed is to wed the crowd. For the perfect flâneur, for the passionate observer, it’s an immense pleasure to take up residence in multiplicity, in whatever is seething, moving, evanescent and infinite.” Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life

Charles Baudelaire may not have been the first man or woman to wander the streets of his city with no particular destination, and no purpose other than to absorb his surroundings, muse on whatever took his fancy and end up somewhere interesting, but he was the first to give it a name: the flâneur. The word comes from the 17th century term flânerie – to stroll or idle without purpose. Baudelaire was not alone in his flânerie. Many of his 19th century literary peers celebrated the art of flânerie, including Balzac, Anaïs Bazin (who declared that “the true sovereign of Paris is the flâneur”) and Victor Fournel. All agreed that there was more to being a flâneur than simply wandering the streets. By deliberately avoiding the end point of a destination, the flâneur throws himself open to whatever he might encounter.

This was further expanded by Andre Breton, who in his 1928 novel Nadja advised the reader always to be in a state of disponibilité – “the availability, the waiting, the opening to the unpredictable which breaks the frozen crust of existence, and finally the change.” So the flâneur is actually in search of something while he wanders, yet he doesn’t know what it is until he finds it. This is not unlike when one is on holiday and goes out in search of a bureau de change and ends up buying an expensive embroidered rug. Sainte-Beuve wrote that to flâne is the very opposite of doing nothing. Just as an idler attaches a philosophical meaning to the art of loafing about, so a flâneur creates an air of mystery and intrigue during a leisurely stroll. This is obviously much easier to do in a city such as Paris or Marrakech than Milton Keynes, though the true flâneur would argue that one can flâne anywhere.

Walter Benjamin wrote an enormous, unfinished work from 1927-1940 called The Arcades Project, in which he studied the flâneur via the poems of Baudelaire, coming to the conclusion that “The flâneur was a figure of the modern artist-poet, a figure keenly aware of the bustle of modern life, an amateur detective and investigator of the city, but also a sign of the alienation of the city and of capitalism.” After writing his book for 33 years, Benjamin eventually summed up the nub of the flâneur: “The great reminiscences, the historical frissons – these are all so much junk to the flâneur, who is happy to leave them to the tourist. And he would be happy to trade all his knowledge of artists’ quarters, birthplaces, and princely palaces for the scent of a single weathered tile – that which any old dog carries away.”

So the flâneur bypasses all tourist sights and monuments, seeking his own particular set of archaeological points of interest, to which he may, or may not, return to one day. The flâneur’s map, if he ever carried one, would be marked with symbols showing, for example, ‘nice quiet café’, ‘pretty lady reading book in park’, ‘tramp who looks exactly like Daniel Craig’. Most of us manage to enter the realm of the flâneur when on holiday, while in daily life it is more difficult to nurture the air of the artist-poet while dodging around all the chuggers, muggers and beggars, with one’s field telephone beeping constant notifications that so-and-so has responded to our friend request. The genuine flâneur does not request friendship; he is perfectly content to strike up passing acquaintances with people he will never meet again. Some ardent flâneurs have argued that only certain cities provide the true flânerie experience, most of them putting Paris at the top of the list. Rome is often rejected as being too full of distractions, London as too big – though Iain Sinclair managed it, turning his flânerie in the capital into a thing he called psychogeography. We’d rather stick with ‘flâneur’, thank you very much.

The Baudelaire version of a flâneur was always male, principally because solitary 19th century women wandering around the city probably wouldn’t be left alone long enough to enter a reflective state of mind. But more recently the ‘flaneuse’ has been celebrated, by writers like Lauren Elkin in Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice, and London. In Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City, the writer spends a long time walking about the streets of New York to get over a break-up. She starts off quoting Baudelaire and his flâneur, but ends up writing about how virtual modes of communication have replaced more traditional forms of exploration and community. She finds reconnecting with the physical body of the flâneur (all that walking can be quite exhausting) more helpful to ease her heartbroken mind.

There is, too, a relatively new phenomenon known as the cyberflâneur, or at least there was in the 1990s during the internet’s early days. As Conor McGarrigle puts it, “With no Google or Facebook to organize the internet’s information, surfing the web was an art, successfully practiced by the cyberflâneur, the web connoisseur […] One presumes that, as the flâneur resisted the temptations of consumerism, so the cyberflâneur eschewed the commercialization of the web.” He concludes that the cyberflâneur has been made redundant: “For platforms such as Facebook, any possibility for flânerie has been successfully engineered out.”

The demise of the Baudelairean flâneur was blamed on the modernisation of the streets of Paris by Baron Haussmann, the Mark Zuckerberg of 19th century town planning. Haussmann replaced many of the nooks, crannies and arcades beloved by wandering poets with wide boulevards where flâneurs felt too exposed to the crowds. Flâneurs seek shadows, passages, dead ends and blind alleys. Luckily, those who tidy up the Internet for us cannot do the same to the streets of our cities. The possibility of flânerie will never disappear, for those who seek the simple pleasure of wandering with no destination, safe in the knowledge that they won’t end up on Amazon or a porn site after a few wrong turnings. So if you live in a city and you fancy a leisurely stroll but have no idea where you want to end up, you are already half way to being a flâneur.

Main photo: Pierrot Le Chat

Fellow Chaps,

Fear not! I am here, your Flaneur in La La Land: Jack Enyart!

As you will see from my website (link below) I have been keeping Chapdom alive here in Hollywood for a lifetime.

Therefore I submit myself to appear in your upcoming issue:

I have at least a half-dozen choice snapshots, to be accompanied by breezy narrative, for your consideration.

How do I deliver this material to you? (Keep the instructions right-brained, so far as possible.)

A Bounder Across the Sea,

JACK ENYART

http://www.jackenyart.com

[…] A short history of the Flâneur […]

Dear Sirs,

I have just read a very interesting article about your institution in the french magazine “Courrier international ” and would be happy to apply for your newsletter. Thank you and Best Regards .

Eric L. Rongvaux

[…] The flâneur boulevardier dandy gentleman charles baudelaire paris walter benjamin the painter of modern life poet flaneuse lauren elkin iain sinclair olivia lang — Weiterlesen thechap.net/2019/05/20/the-flaneur/ […]

[…] Photo courtesy of The Chap […]

[…] courtesy of The Chap and Emile […]

Congratulations on this wonderful article. I particularly enjoyed your analogy between the ‘modernisation’ of the internet and the streets of Paris (and, I expect, the destiny/fate of all cities). It reminded me of William Blake and London’s “chartered” streets. Would it be right is saying that with the streets opening wide up, there was the danger of the flaneur moving from out of the shadows from object to subject? This is a moot point because the essence of the flaneur’s pleasure was not in being a complete loner but being lost in the crowd (in Baudelaire’s words “taking a bath in the multitude”), and through this the act of “divine prostitution”- a vital component in the flaneur: living vicariously through others and imagining their lives, histories, joys and woes.

[…] raiment that exists on Earth, and to keep walking until it is decided that pause must be taken. Flâneur is a French-coined term for a person who explores the city, allowing wit, whim and curiosity to […]