Louis Christou on how his attempt to join the O.T.O. led to an interest in artist, occultist, Thelemite, visionary and hermenaut Austin Osman Spare.

In my late twenties, I briefly dabbled in the murky waters — or in Sigmund Freud’s words, the black tide of mud — of occultism. I read Colin Wilson’s tome on the subject, and followed that with his biography of British occultist, poet and mountaineer, Aleister Crowley. Aleister Crowley: The Nature of the Beast left me with more questions than answers regarding the so-called Wickedest Man in the World, so I pored over his former disciple Israel Regardie’s weightier The Eye in the Triangle. Although more comprehensive than Wilson’s slim volume, it likewise succeeded in whetting, rather than sating, my appetite for the Great Work of the self-styled Vicegerent of God Upon Earth.

In each of those books, I had come across the words Ordo Templi Orientis — a secret occult society of which Crowley assumed leadership after the death of its co-founder Theodor Reuss, who had inducted Crowley in 1910. He reshaped O.T.O, revising its rituals and structure to conform with his self-created religion Thelema. A cursory Internet search informed me that the magical order still existed, and through its website I was able to express a desire to join.

I arranged to meet two of its members at a public house in Holborn; I was instructed to identify them by the copy of Crowley’s Book of the Law on their table. But the pub was busy and I was unable to find them. After ten minutes of desultory ambling and staring at seated strangers’ midriffs, I received a WhatsApp message comprising a cryptic series of emojis, which apparently indicated the members’ whereabouts. Having failed to decipher the code fifteen minutes later, I received another, slightly less abstruse, series of emojis that suggested the Thelemites were becoming impatient: [Ghana] [bee] [ear] [owl] [4 king] [night] … [face with rolling eyes]. When I finally located them, they gave me a recommended reading list and suggested that I attend a Gnostic Mass service a fortnight later.

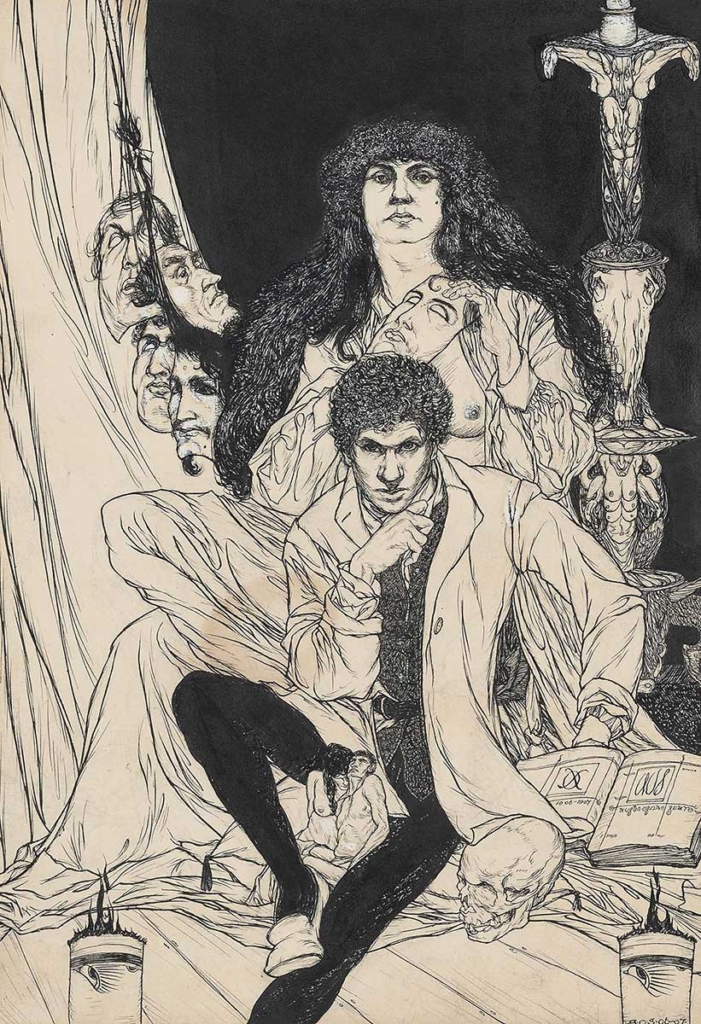

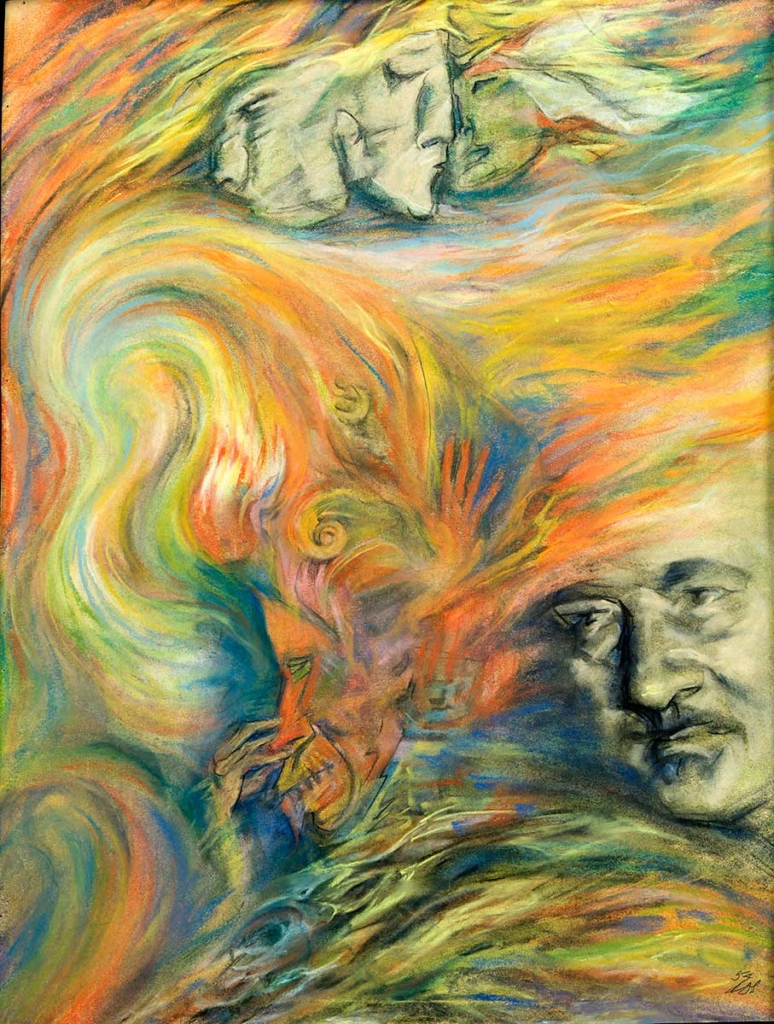

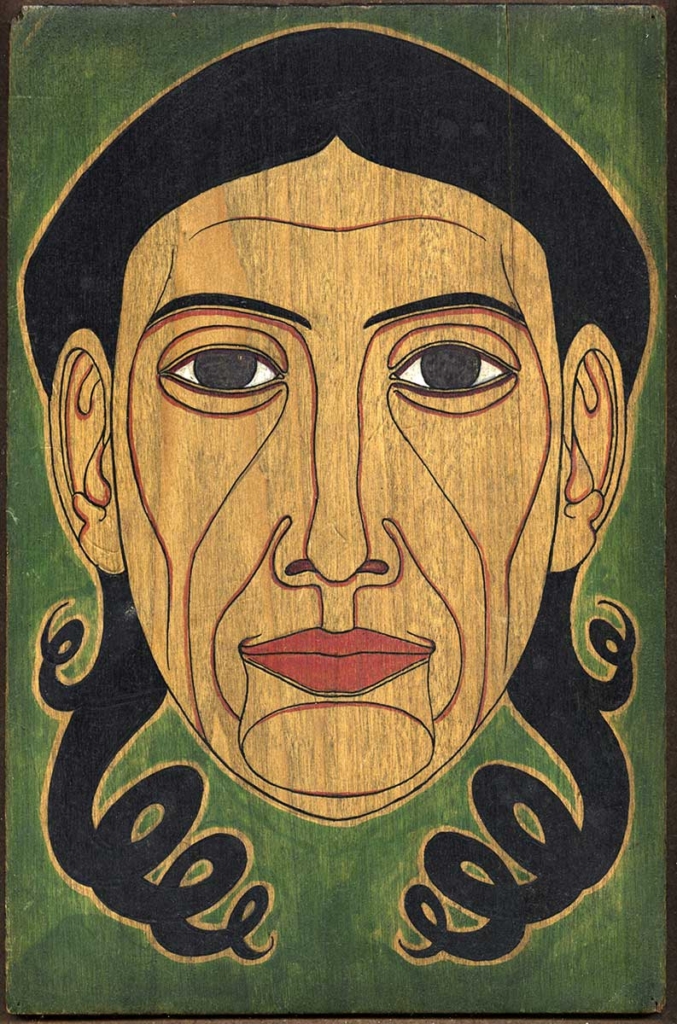

One of my new acquaintances greeted me outside The Bonnington Centre in Vauxhall. She was wearing a short-sleeved dress and I noticed the colourful tattoos that decorated her left arm — otherworldly portraits and landscapes, which, she told me, were inspired by the paintings of the visionary artist Austin Osman Spare. A self-mythologising magician who blurred the line between reality and fantasy, this erstwhile associate of Crowley’s and enfant terrible of the Edwardian art scene piqued my interest. Knowing very little about him, I wanted to learn more, but the ceremony was about to begin. We went upstairs and took our seats facing a velvet curtain in an otherwise prosaic room. The curtain was raised, and a voluptuous priestess appeared, sitting cross-legged and revealing large, bare breasts.

To be perfectly honest, I’ve retained very few other details from the ceremony that day. I was distracted; I wanted to plunge headlong into that fabulous Spare…

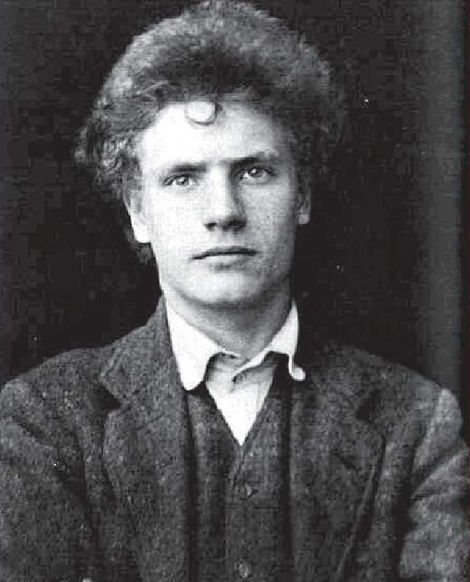

Born within the sound of Bow Bells in 1886, Austin Osman Spare qualified as an authentic cockney. His father, Philip Newton Spare, had moved from Yorkshire to London and joined the City of London Police in 1878. The following year he married Austin’s mother, Eliza Osman, at the Wren church of St. Bride’s on Fleet Street. They lodged with other police families in a tenement called Bloomfield House, opposite the grand entrance of Smithfield Market.

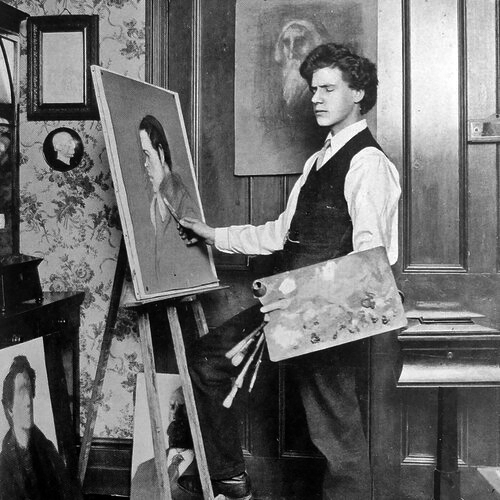

The family later moved south of the river to Kennington Park Gardens, a few streets away from Charlie Chaplin. Spare attended a school at nearby St Agnes church, where he was exposed to the type of ritualism and religiosity that overlaps with the occult. By the age of twelve, it was apparent that he possessed a precocious artistic ability, and he started attending evening classes at Lambeth Art School. After a brief apprenticeship with a printer and poster designer, he began working at a glassworks in Whitefriars Street. While there, some design work that he had been doing was noticed by two distinguished visitors, who recommended him for a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in South Kensington; an establishment that proved to be a great disappointment to Spare (and, incidentally, suffragette Sylvia Pankhurst — his friend and future neighbour). Indirectly influenced by Aubrey Beardsley, to whom he would frequently be compared, and more obviously inspired by Charles Ricketts, Edmund Sullivan and George Frederic Watts, Spare was a preternaturally talented draughtsman. In 1904, he had his first public showing in Newington Public library on Walworth Road, and, after his father submitted two of his drawings to the Royal Academy, he became famous as their youngest exhibitor.

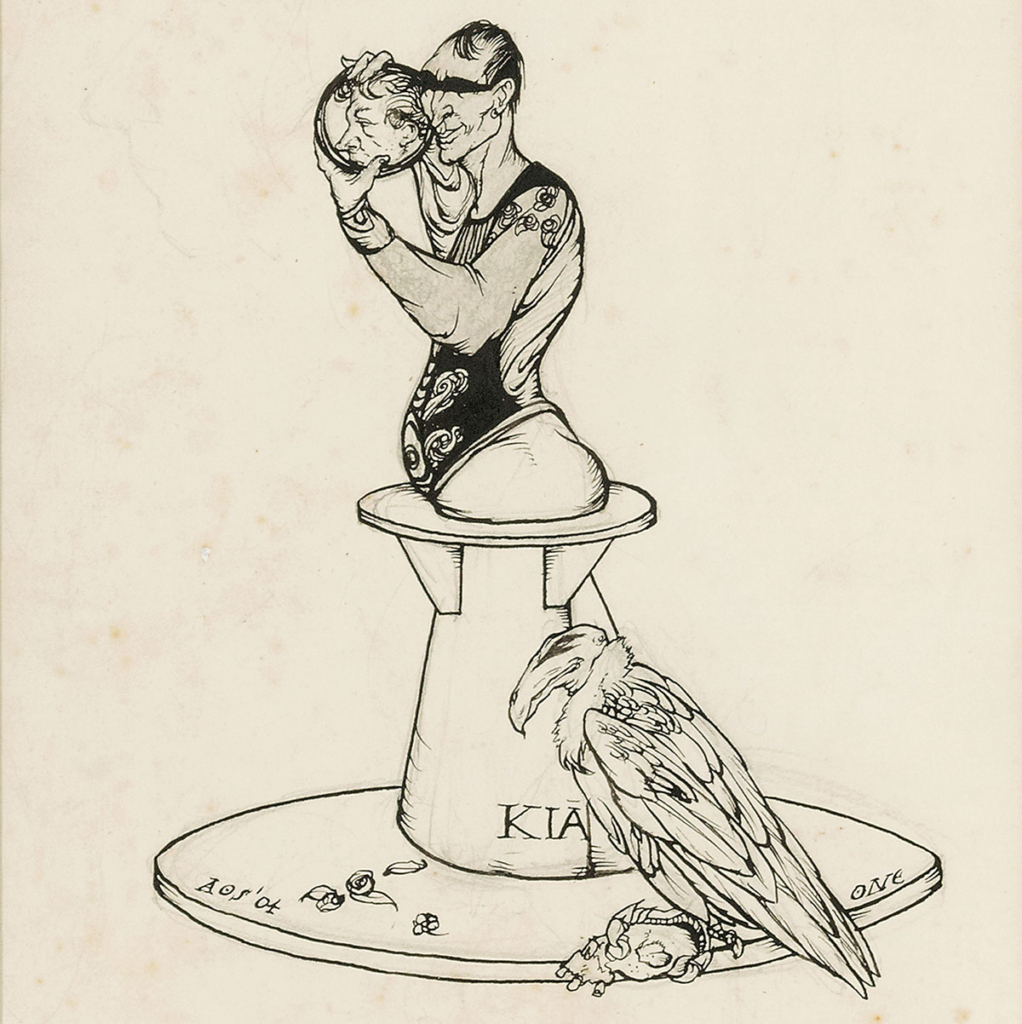

Not long after, he published his first book, Earth: Inferno, in which he postulated that Earth is already hell — a convincing and prescient theory considering he would go on to live through two world wars and end his days in a squalid South London basement. It was around this time that he started devising his own cosmology: an elaborate philosophical system centred around what he called Zos and Kia. Zos being the corporeal body — including the ordinary mind — and Kia being the universal Mind or God, akin to the Hindu Brahman or the Tao of Chinese philosophy. Spare had a lifelong interest in Theosophy, Buddhism and Spiritualism, and a belief in the ability to manipulate his unconscious, conjuring elementals and psychic entities. An obsession with bric-a-brac, props and junk is apparent in the exquisitely detailed self-portrait he produced a few years later, now in the collection of Led Zeppelin guitarist Jimmy Page. One of several musicians, including the late Genesis P-Orridge, who have owned Spare works and contributed to his posthumous renaissance and cult following.

Spare met the infamous Crowley at the former’s first West End showing on Bruton Street. It’s likely that Crowley owned drawings by the young artist. It’s also a possibility that the two of them had a physical relationship; Crowley was avowedly bisexual, and Spare was known at the time to enjoy the patronage, admiration and friendship of gay men. He became acquainted with the French poet Marc Andre Raffalovich and his companion John Gray — former friends of Oscar Wilde — through the milieu that surrounded Mayfair publisher John Lane. Spare designed bookplates for Lane’s Bodley Head imprint. Speculated sexual proclivities notwithstanding, Spare married chorus girl Eily Shaw in 1911 and they set up home in Golders Green. Perhaps attempting to assimilate and ingratiate himself with his new neighbours, he began exploring Jewish literature, reading The Song of Solomon and The Zohar.

By the 1920s Spare was single again and, with his career foundering, had become something of a recluse, increasingly exploring inner realms and experimenting with automatic and psychic drawing. A 1936 newspaper headline hailed him as the progenitor of surrealism. But, as Spare authority and biographer Phil Baker put it, this didn’t mean he was rubbing shoulders with Dali and Breton. Somewhat less glamorously, he was residing in a studio above a Woolworth’s in the Elephant and Castle, producing stylised pictures of film stars and pastel portraits of working-class cockneys who lived nearby. In 1947, he had an unsuccessful comeback show at the Archer Gallery on Westbourne Grove. By 1949, needing a more accessible alternative to the gallery system, he had begun holding affordable exhibitions in South London pubs, the last of which was at the Mansion House Tavern on Kennington Park Road.

Austin Osman Spare died in obscurity on 15th May, 1956. The world’s largest public display of his work can be found in ‘The Spare Room’ in The Viktor Wynd Museum — featured in the spring edition of The Chap — where you can also pick up a copy of Phil Baker’s excellent Austin Osman Spare: The Life and Legend of London’s Lost Artist.

A few days after the Gnostic Mass, I met the two O.T.O. members at a café in Hampstead. They offered to be my requisite sponsors if I decided to join, and gave me a Minerval Degree consent form to complete. Not entirely sure what I was consenting to, I signed the bottom of the headed paper anyway. I was told to expect an email inviting me to an initiation ceremony. A more pressing concern for me, however, was the Thelemites’ failure to mention thus far the thing that initially attracted me to their secret society: sex magick. Too reserved to enquire in person, I sent a WhatsApp message later that day to my Spare enthusiast/sponsor. She informed me that, while it is widely known that O.T.O. teaches certain secrets of sex magick, she was unable to reveal any of those secrets to me. Assuming she was being coy, and perhaps getting a little overexcited, I replied with an arcane emoji of my own: [aubergine]. Her profile picture suddenly disappeared, replaced by WhatsApp’s default one — unlike my overactive sacral chakra, I was blocked. I’m still waiting for my Minerval Degree invitation.

Here’s hoping your overactive sacral chakra finds solace elsewhere, Mr Christou.

What a thoroughly enjoyable account of a flirtation with the occult – bravo, sir!