Tom Cutler:

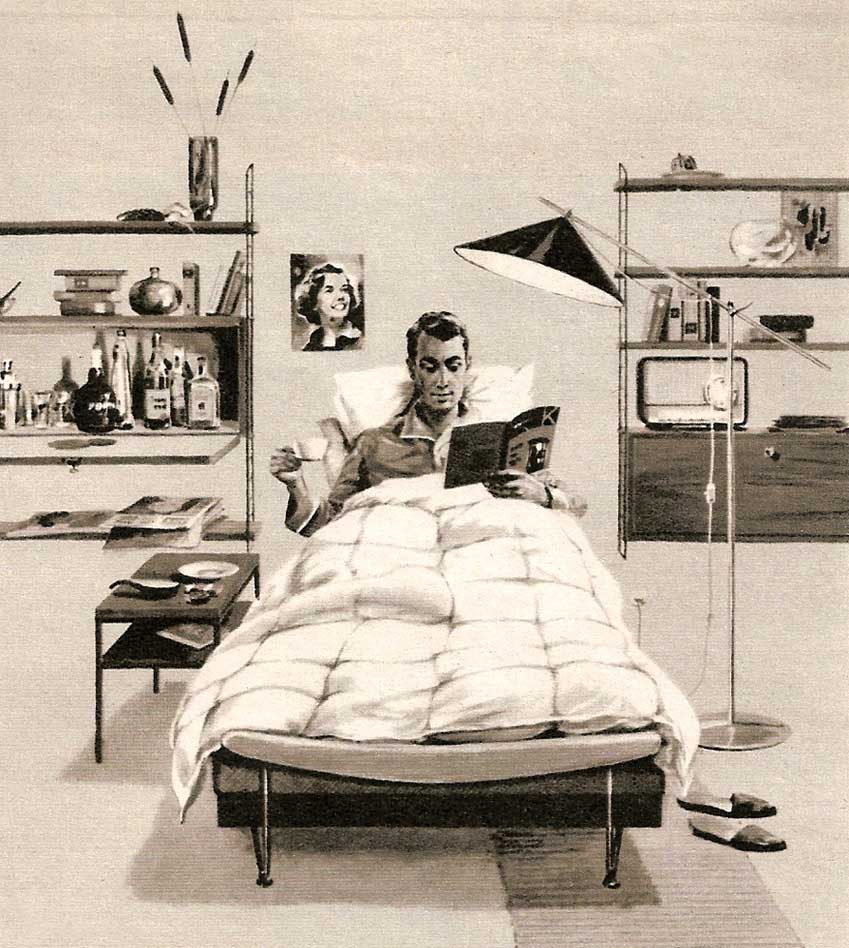

I think it was Samuel Goldwyn who said that a bachelor’s life is no life for a single man. This might be true; I wouldn’t know, not being a bachelor any more, but surely it has its good points, even for the unattached gentleman. You can get home when you like, you can smoke your pipe in bed, you can fry up hot dogs and unearthly chili concoctions till steam weeps down the walls, or eat crisps in front of The 39 Steps wearing the slippers nobody except you likes. In short you can please yourself. You don’t need to worry about spilling industrial-strength coffee on the cushions, because you haven’t got any cushions, you can have gin for breakfast, eat fried eggs with your hands, and listen to The Laughing Policeman or The Day King Henry Got His Hampton Caught without suffering opprobrious gripes. You can have pals round for a game of cards with long cigars, and – let joy be unconfined – get in the bathroom whenever you please.

But, perhaps best of all, you can have a lady round to your bachelor pad. It should be remembered, of course, that there are some things that aren’t a bachelor pad. For example, a typical student bedsit is not a bachelor pad. Or not usually. When I was a student, I had a friend called Charles who lived in a bedsit next to mine at the top of a skinny red house, and he managed to make his single room a bachelor pad with knobs on. He used to bring a different girl home every night, and, if he was entertaining a lady of taste and refinement, he would ask for the loan of an LP of something designed to look esoteric from my scratchy library of music – Come Ye Sons of Art, say, or, Noye’s Fludde.

Bachelor is a funny word that looks like it should have a T in it. My favourite definition is ‘A man who comes to work each morning from a different

direction’

Charles’s room, as tiny as my own, had bottles of wine in a wine rack constructed from an old chest of drawers; there was Scotch, gin, and sherry on a silver tray, fine cheeses maturing on the mantelpiece, and long tall shelves of interesting books. On the walls hung prints of eighteenth-century prizefighters, and on his nautical desk sat a majestic pipe rack stuffed with briars, clay ‘tweenacts’, and a rosewood churchwarden. Charles was apt to sit of an evening reading in his leather armchair, and would sometimes invite me in to share a deep-cut crystal tumbler of Scotch and a pipe or two beside the amber resplendence of the crackling fire that he kept going in the tiny grate in winter. But I was more than once unceremoniously turfed out when one of his lady-friends arrived on the off chance.

Compared to my oblong hulk of felt and iron, Charles’s bed – his most important piece of furniture – was a picture of luxury. Mine had an old ship’s blanket thrown over it; his was covered with a fine counterpane. He always made this bed with military precision, and its lavender-smelling hospital-corner-folded sheets were as dazzlingly white as a urinal in summer, and of such starched crispness it made you gasp to look at them. ‘How did you get them to look like that?’ I once asked.

‘Suzanne at the dry cleaners comes in with them Tuesday and Friday, he said, taking the tip of a nail file around his cuticle.

‘Comes in?’, I said.

‘Well, she brings them in starched, puts them on the bed, we have a bottle of wine, and then, you know, test ’em out.’

He was a card, that Charles. I wonder what happened to him. He still has my LP of Sibelius’s Second Symphony and my first edition of Ulysses.

My bedsit was nice enough, I suppose. I had an oil burner instead of a coal fire, and ordinary cotton sheets instead of lavender-smelling articles as brisk as asbestos. I had books aplenty, and tins of assorted loose teas, and pipe tobaccos. I had snuff by the drawer-load, but no alcohol to speak of – I couldn’t get it to last long enough. A frogged dressing gown hung on a brass hook on the back of the door, there was a Turkey rug on the floor, and on the wall I had a few black and white photographs of nude ladies, which a girl with whom I became friendly said had piqued her interest. Visitors remarked on the perfumes of coffee, and pipe smoke, and toast, and shoe polish, and, though the definition of bachelor pad is rather vague, my bedsit was, I’m sure, the real thing.

Bachelor flats were one of the specialities of Roy Brooks, a London estate agent with an address near the Moravian church in the King’s Road. From the 1950s until his death in 1971, Brooks drove clients in his Rolls Royce to the places he sold, mainly in Pimlico, Chelsea, and up-and-coming Islington. He was famous for the witty advertisements for crummy properties that he put in the Observer. Some of these ads appeared in a book called Brothel in Pimlico, published by John Murray in 2001: ‘FABULOUS FLAT… Bookshelves contain real leather-bound books. A kind of legal air hangs over the vast studio-type, chandelier-lit drawing room… Air of rich luxury abt. bathroom with its interesting prints…’ Then there was, ‘On still nights the friendly howl of the Hyena floats over the Mappin terraces & one can, maybe, imagine oneself far away from our acquisitive society.’ Or, ‘Under its mantle of dust and dirt this is a very fine house, there is even an air of aristocratic decay about the broken passenger lift.’ This is the world in which bachelor pads ought to be situated and, indeed, the zone where bachelors themselves ought to hang out.

Bachelor is a funny word that looks as if it should have a T in it. It’s from the thirteenth-century Old French bacheler, meaning ‘youth’ or ‘squire’. One of my favourite definitions is, ‘a man who comes to work each morning from a different direction’. The word’s meaning was once discussed by Raymond Burr, who played the murderer in Hitchcock’s Rear Window – set in a world of bachelor pads, loneliness, and anonymous living. Burr was a bachelor only in the coded sense of the word. ‘A bachelor, according to the dictionary, is a man who has never been married’, he told a reporter in 1957, ‘An unmarried man is not married at the moment. Many of these terms have fallen into disuse.’ Though this remark was calculated to conceal his homosexuality, it was true in the sense that the word has indeed gone the way of ‘much obliged’ and ‘counterpane’. When was the last time a newspaper referred to someone as ‘a bachelor’?

The bachelor pad in David Lean’s Brief Encounter, where the hero played by Trevor Howard takes the woman played by Celia Johnson for what turns out to be nothing more than a cuddle, belongs to one of his bachelor friends. This scenario prompted Billy Wilder to wonder what sort of bachelor would lend out his pad for other people’s romantic engagements, and he came up with The Apartment, the best bachelor-pad film of all time. If you don’t know it, track it down.

The perfect opposite of the bachelor pad is described in The Big Sleep by Raymond Chandler: ‘The room was too big, the ceiling was too high, the doors were too tall, and the white carpet that went from wall to wall looked like a fresh fall of snow at Lake Arrowhead.’ No fitted carpets for Chandler’s bachelor private eye Philip Marlowe. It was masculine rugs and polished boards, and books, and tobacco smoke, and that last inch of steel.

Films and television gave the BP a particularly good publicity boost during the Swinging Sixties. David Niven and Peter Sellers cropped up in films without number at the time, reclining against the mantelpieces of glossy bachelor pads sprinkled with tiger rugs, with pretty girls squirming around on buttoned leather sofas. Any young man who was any young man seemed to have one. Jimi Hendrix had his London pad in Upper Brook Street, right next door to George Frederic Handel’s.

Then there was that fellow called Stephen Ward who organised Viscount Astor’s pool party at Cliveden – the one at which Christine Keeler got out of the water naked and Secretary of State for War John Profumo did an unwise thing and got his come-uppance. Ward had been a carpet salesman in Houndsditch before becoming a sort of society osteopath who squeezed the deltoids of anyone who mattered, including Winston Churchill, Mahatma Gandhi, and Anthony Blunt. At Profumo’s trial Ward was accused of living off the immoral earnings of his stable of ‘girls’, who, actually, appeared to be living off him at his charming mews flat, which was a bachelor pad par excellence. Sadly, the unforgiving massage the Establishment gave him in court did not have a happy ending. He took an overdose of tablets.