Gustav Temple reviews the new documentary about the life of Humphrey Bogart.

“I like people, yachts, chess, politics, a good drink, a good wife, nice kids. I had those.”

Humphrey Bogart

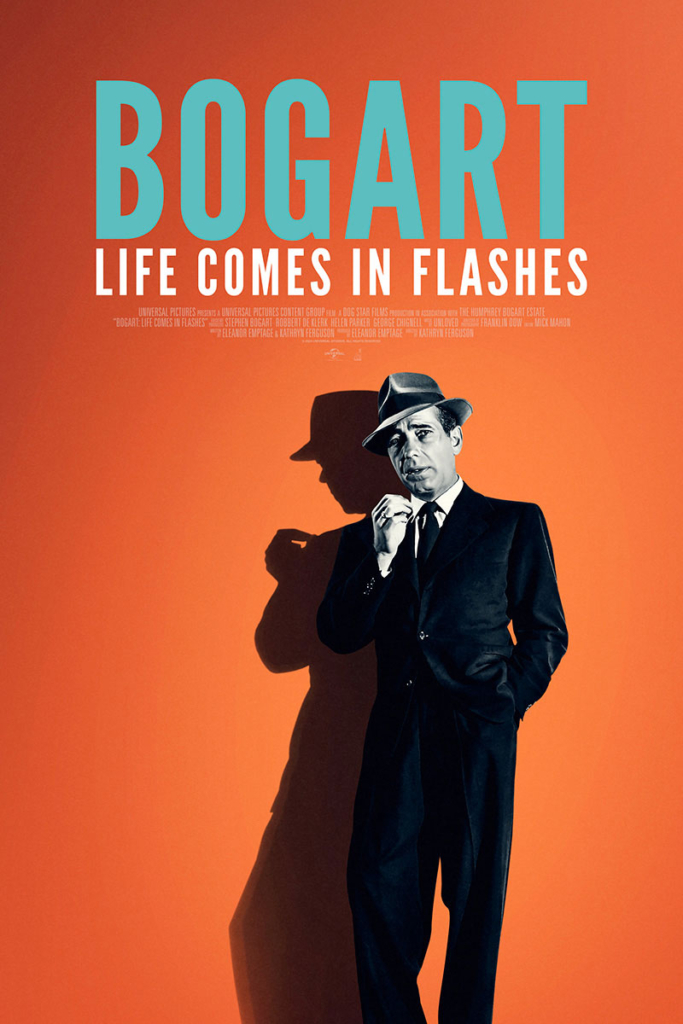

Hollywood’s ultimate man’s man, and his troubled relationship with alcohol and history of treating his many wives roughly, may not seem the ideal subject for an all-female production team. But the new documentary about Humphrey Bogart is the first of its kind in many ways. The first to have the full blessing of his son Stephen Bogart, and the first to use Bogart’s own words as the central narrative. The film was written and directed by Kathryn Ferguson and produced and co-written by Eleanor Emptage, whose previous collaborations include Nothing Compares, a 2022 feature documentary about Sinéad O’Connor’s music and activism.

In an era when we are bombarded with biopics offering us glossy portraits of stars from the golden age of Hollywood with all the grit and dust cleaned off, it is refreshing to watch a film that wades into the heart of Hollywood life in the 1940s and fifties and tells it how it was.

“Do I throw things?” asks Bogart’s third wife Mayo Methot. “Oh yes, but never things I really like. Metal ashtrays are fine for throwing; phonograph records are superb. They make such a satisfactory crash. If you’re too tame you’re half dead. Bogie and I like excitement, we need it.” The quotes the director chooses to use, with actors voicing the women in Bogie’s life, show that some of his women could give as good as they got.

Everyone thinks of Humphrey Bogart and Lauren ‘Betty’ Bacall as the uber Hollywood couple of the 1950s, having met on the set of To Have and Have Not (1944) when Bacall was just 19. But Bogie had been married three times before that, and had a string of mediocre potboilers under his belt before the studios hit upon him as leading man material and cast him the Maltese Falcon (1941). By then he was 42, born on Christmas Day in 1899. The original choice for the role had been George Raft, but, as Bogie himself put it, “I was the first Sam Spade. I don’t have many things to be proud of, but that was one of them. The trench coat has become a trademark.”

After that, unless he was playing a cowboy, Bogie rarely appeared in films without the trademark trench coat and dark grey Fedora. Italian hatters Borsalino made the one he wore in Casablanca (1942). Hat aficionados may like to know that it’s made of brushed Sebino grey felt, with a high 12-cm dome and medium 6.5-cm brim, with a Lavagna grey band and silk lining. Non-hat aficionados may wish to know that it’s just about the coolest titfer a man can wear.

One reason for the sudden escalation of Bogie’s fame after the Second World War is offered by commentator Alistair Cook in the documentary: “After the gangster era, Hitler was acting out scripts far more brutal than anything the Capone gang or Warner Brothers had ever conceived. At that point, when reality was so gruesome, you could not have heroes with curly hair and soft voices like Leslie Howard. They were suddenly dated.”

Or it could simply have been that the actor starred in what is still one of the most iconic movies of all time, Casablanca, and would forever be remembered as the dude in the tux who said ‘Play it again, Sam’ – even though he never actually uttered that line in the film.

Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes presents the truth about Bogie’s relationship with all the women he met before Lauren Bacall (who tamed him and didn’t put up with any nonsense), without any direct comment or criticism. Instead, the director presents the facts and allows the viewer to come to their own conclusions. This also applies to Bogie’s reckless approach to his own physical health and his view of the place of children. There is not a single shot in the entire film, either still or moving, where Bogie doesn’t have a cigarette in his hand or mouth. If he isn’t smoking one, he’s taking one out of the pack to light it or stubbing one out. He fulfils the Martin Amis comment about being so addicted to cigarettes that he had a craving to smoke one even when he was actually smoking one.

Home cine footage aboard his yacht Sirocco shows he and Betty chain smoking on the high seas, overlaid with quotes from Bogie about how much he loves the healthiness of sailing and getting away from Hollywood gossip. And when it came to the booze, there is no shortage of footage of Bogie necking endless bourbons on the rocks, dry martinis or gin, although he is never seen with anything as lightweight as a beer.

“I don’t trust anybody who doesn’t drink. People who don’t drink are afraid of revealing themselves.” Humphrey Bogart

The comments from other actors and directors are well chosen, ranging from John Huston to Katharine Hepburn to Louise Brooks, the latter known principally for her career in silent movies. Brooks (or at least an actor playing her voice) comments about how well cast Bogart was in In a Lonely Place (1950): “He played one fascinatingly complex character who captured Bogart’s own isolation amongst people. The film character’s pride in his art, his selfishness, drunkenness, his lack of energy stabbed with lighting flashes of violence, were shared by the real Bogart.”

Once he married Lauren Bacall on 21st May 1945, the man’s man calmed down a little, and was able to turn his attention to interests other than boozing and violence. As McCarthyism swept the nation and infiltrated the Hollywood machine, he and Bacall formed a group to defend the rights of Hollywood writers not to declare their political leanings. The film is careful to point out that the issue at stake was free speech, not politics, ie Bogie was no commie but wanted the communists left alone. When the press started attacking him, he was forced to give a humiliating press conference, declaring himself not to be a communist purely to save his career. He was just in time to avoid Jack Warner’s blacklist that ended the careers of many in Hollywood.

When Bogart and Bacall sired their only child, Stephen, in 1949, they were over the moon, especially with an age gap of 25 years between mother and father. When Stephen was aged two, Bogie got the part in The African Queen (1951), directed by John Huston, which would take him out of the country for six months. Betty immediately knew what she had to do – find a good nanny. Bacall decided to join her husband on set in Africa for the whole six months, travelling via Paris, probably to keep an eye on him and co-star Katharine Hepburn. The nanny saw them both off at the airport – then promptly dropped stone dead with the boy Stephen in her arms.

The director overlays this shocking anecdote with footage of Bogie and Betty at fashion shows in Paris, while their son languishes thousands of miles away with a new nanny for six months. “I love Paris,” says Betty. “And of course I’m here to see all the fashion shows.” Bogie, hovering beside her, doesn’t say anything and reaches into his jacket for another cigarette.

The tobacco ensured a speedy decline for Bogie, who died aged 57 of lung cancer. His final weeks are grimly chronicled in the documentary, though fortunately without any actual footage. Too ill to take the stairs, his valet would dress him in a smoking jacket – of course – and carefully place him in the dumb waiter to come downstairs and play the role of host to his family. He was propped up in a chair but could hardly sip his bourbon. His friends were rarely invited over, as he didn’t want them to see him like that.

Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes has the polished grandeur of a Hollywood movie; so much more satisfying and revealing than yet another slick biopic starring someone like Jacob Elordi. The choice of background music is odd and occasionally out of kilter – the producers chose Unloved for all the tracks. This Los Angeles trio’s etherial, moody soundscapes with lyrics about heartbreak and loneliness are closely associated with the television series Killing Eve. Despite this, their familiar music does bring the tale of Bogie’s short life into the present, giving the story a depth that might not have been conveyed by the big band swing music of Bogart’s era. We should simply be grateful that they didn’t “Play it again, Sam” and use the theme song from Casablanca.

Bogart: Life Comes in Flashes is available on digital download from 9th December 2024