Sunday Swift:

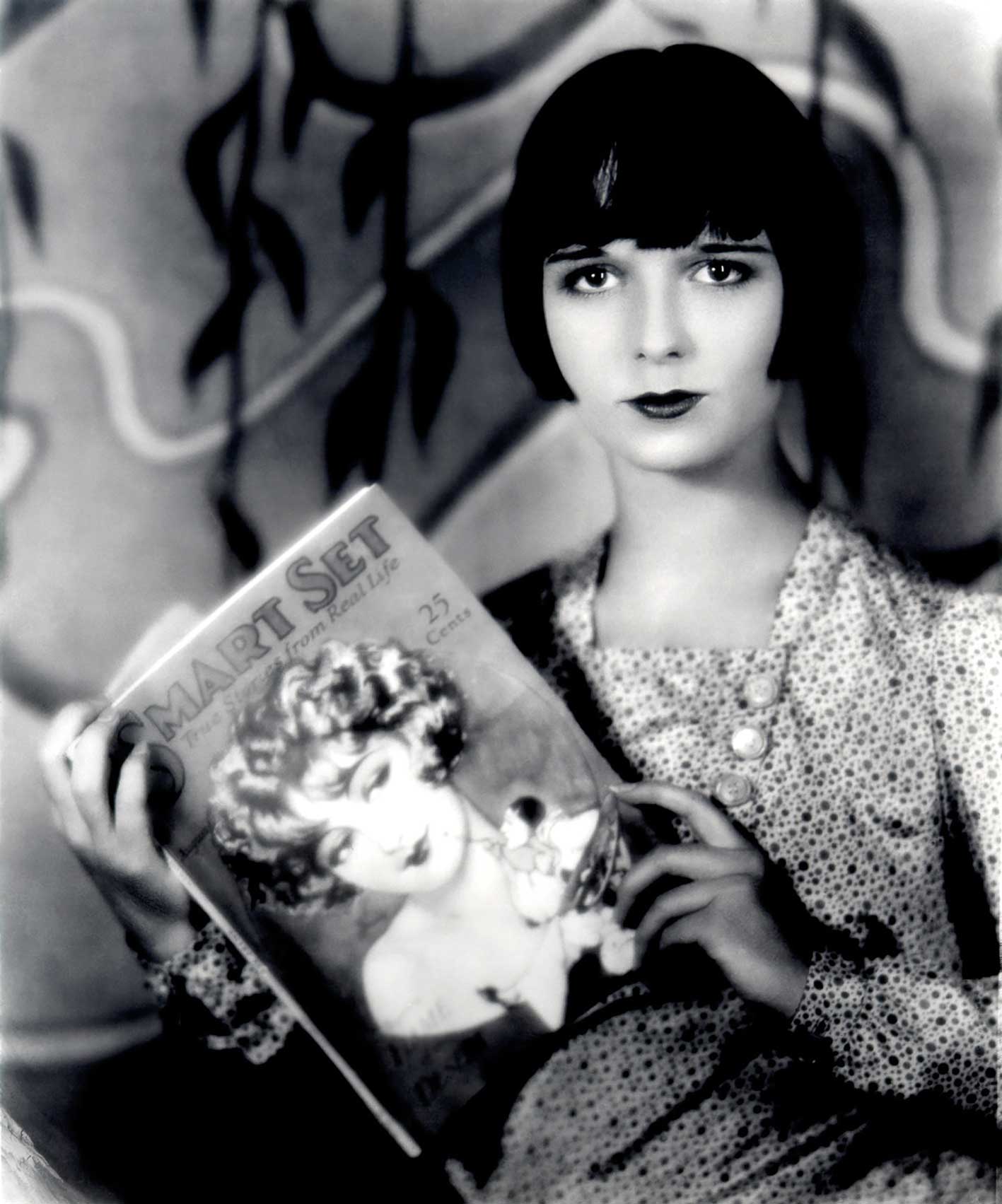

In some ways, silent film star Louise Brooks has much in common with Jackie Kennedy Onassis (the subject of my previous Dandizette profile): each were highly intelligent and strong-willed women who became trapped in a world they longed to escape. Louise once said, “There is no other occupation in the world that so closely resembled enslavement as the career of a film star”. Where Jackie eventually became a prisoner to her own image, however, Louise seemed to feel imprisoned in her life no matter where she was.

Born in Kansas in 1906 to parents who could most politely be described as ‘disinterested’, Louise was a talented dancer – in fact, by age 10, she was working professionally. Eventually, though, she was dismissed for having a ‘superior’ attitude – an experience to be repeated often throughout her life. She moved to New York City to work as a chorus girl (eventually evicted from the dancer’s apartment house for promiscuity). Somehow, by the age of 19, she found herself acting in films.

Louise’s turbulent film career only spanned from 1925-1938, and during this time she made only 24 films (although she always insisted that she had “no film career”). Those who did adore her did so lavishly: cinema archivist Henri Langlois, for example, declared, “There is no Garbo, there is no Dietrich, there is only Louise Brooks!” Like fellow dandizettes Garbo and Dietrich, however, there was no doubt that Louise Brooks was not universally adored. Brooks herself quipped, ‘I have a gift for enraging people, but if I ever bore you it will be with a knife’. She was extremely intelligent – and brash enough to refuse to allow others to treat her as anything less. This made her rather unpopular with male Hollywood filmmakers. In a documentary on Louise, biographer Barry Paris suggested that the studio executives “couldn’t believe someone so beautiful could be smart. And she was not gentle with them.”

‘I have a gift for enraging people,’ Louise Brooks once quipped, ‘but if i ever bore you it will be with a knife.’

At the high point of her career, Louise kept a close group of friends in New York (she was particularly fond of Humphrey Bogart), married (and then divorced) twice. She even had an affair with another silent film star and dandy, Charlie Chaplin. Brooks would later write of Chaplin that “He was a self-made aristocrat. He taught himself to speak cultivated English. […] He loved showing off in fine clothes and elegant phrases.”

In fact, Brooks had a penchant for this self-invention, as she also listed Pygmalion (1938) as one of her favourite films. Like Eliza Doolittle, Brooks came from nowhere and reinvented herself to rub elbows with the crème de la crème of society. However, like Eliza in Shaw’s original ending for Pygmalion, Brooks always seemed to resent the very life she had created for herself.

Two of the films in particular epitomised Brooks in popular culture: Beggars of Life (1928) and Pandora’s Box (1929). In Beggars, Brooks disguises herself as a young boy to escape the law. However, it was really the role of Lulu in Pandora’s Box as the femme fatale that has solidified Brooks in cinema history. Lulu was a naïve ingénue hedonist who seems to crash the worlds of others around her. Director G.W. Pabst had searched for months for the right lead actress as Lulu in Pandora’s Box – he was on the verge of reluctantly signing Marlene Dietrich for the role, but when he found Brooks he signed her instead. Dietrich, Pabst felt, was too knowing and ‘obvious’ for the role of an innocent Lolita-style character.

The film initially opened to unenthusiastic reviews: one complained, “Louise Brooks cannot act. She does not suffer. She does nothing.” Although intended to be a negative attack on the film, this review strongly recalls Charles Baudelaire’s insistence that a dandy ‘does nothing’. Like any good Dandy, it was inactivity that drew Louise to the role. Louise explained that “[Lulu] isn’t a destroyer of men… just the same kind of nitwit that I am. Like me, she’d have been an impossible wife, sitting in bed all day reading and drinking gin.”

Like many films from this era, the 1950s brought a new appreciation for Pandora’s Box, and it is now recognised, alongside Dietrich’s The Blue Angel (1930) as one of the classics of German cinema (and not just because it portrayed one of the first lesbians in cinematic history). Roger Ebert’s take was: “Brooks regards us from the screen as if the screen were not there; she casts away the artifice of film and invites us to play with her”.

This is interesting praise, as artifice and rejection of authenticity is part and parcel of dandyism. Brooks, then, presents something of a curiosity: a dandy who simultaneously presents an appearance of authenticity as well as an untouchable surface identity.

One of the fascinating elements of dandyism is the unlimited variation in form. The classic English dandyism, embodied in Beau Brummell, is often associated with a certain manner of correctness and appropriateness. French dandyism, recognised by Charles Baudelaire in his essays, is often associated with an existential philosophy – one that borders on a theology. And then there’s American dandyism, which is usually associated with a playfulness and frivolity – probably due to camp aesthete Oscar Wilde’s tour through the US to play the character of a ‘Dandy’.

Louise Brooks was a quixotic combination of each of these versions of dandyism: like the classic English dandy, she is often unreadable, shutting down any scrutiny when it seems inappropriate. In Lulu in Hollywood, Louise wrote that she would never write her memoirs because, having been raised in a conservative region of Kansas, she was “unwilling to write the sexual truth that would make [her] life worth reading … I cannot unbuckle the Bible Belt”. Except that this book does, in fact, contain memoirs – and Louise happily discusses her own sexual experiences throughout the book. I would argue that it is a desire to maintain control of a surface persona through concealment. A tell-all would compromise her dandyism, allowing others to see beneath the façade she’d created.

Fighting against this preference for concealment, however, like the American-style camp dandy, Louise has a flair for the dramatic – an electric personality uncontained by a film screen. Her iconic image – in monochrome – represented the carefree jazz-era flapper of the roaring 1920s; playful and camp, carefree, silly, a gin-swilling ingénue who doesn’t always have full comprehension of her ability to dazzle others into doing what she wants.

Except that Brooksie understood, all too well. As an intellectual, outspoken woman with a refusal not to be taken seriously, Brooks constantly fought against the industry, as well as against herself. Despite that brash and playful flapper image, she also proved to be something of a philosopher-artist – a loner burdened with the weight of the world. Like Baudelaire, Brooks fought with an ennui that eventually transformed into disdain for everything around her. It was this side of her that eventually forced her to walk away from Hollywood.

Brooks didn’t appear to mind the divorce from Hollywood, however: she had been threatening to leave Hollywood almost as soon as she’d arrived. She returned to Kansas to teach ballroom dancing, but found that Kansas no longer felt like home – if, indeed, it ever had. She returned to New York, worked in Sales at Sacks Fifth Avenue for two years (she hated it, of course), and struggled with alcoholism, ‘little yellow pills’ and a decline in health.

Abandoned by her close friends in New York for her stint in retail, she relocated to Rochester, New York in 1956 at the pressing of a film curator, James Carr. Hedonistic, voyeuristic and despondent, Louise had, like Dietrich, become a bitter recluse who refused to leave her flat. Carr, however, had encouraged her to watch segments of her own films, resulting in something of a second career for Brooksie, writing essays on Hollywood and various stars like Garbo, Chaplin and Bogart.

She might have referred to herself as a ‘well-read idiot’, but never before had anyone within the industry turned a critical – even academic – eye on the power of cinema and the stars within it. The funny thing about Louise, however, was that penchant for appearing to reveal all when, in fact, working to conceal more. Reading her essays, she seems to give everything away through authenticity – but the more you read, the more you realise how much she’s holding back so much more.

Hugh Heffner (never a favourite figure of mine) is a great admirer of Louise Brooks. While I do loathe to quote him, he does have a great sum-up of the proto-feminist nihilist dandizette that was Louise Brooks: “You can see an independence and an intelligence that, combined with her beauty, were qualities that made her particularly attractive. But also, you can see the self-destructive quality, too. She fought the system from the very beginning, and she paid the price for it.”

Thank you for this interesting look into a woman I greatly admire and wish I could have known. Fascinating that Hefner recognized her worth