Hard-boiled language to go with hard-boiled plots. In fact, everything about Film Noir is pretty hard. Hard urban clutter in hard, rain-sodden mean streets. And the people who live on those streets are hard, too. The characters of film noir are not fulfilled, three-dimensional people. They are ciphers, stereotypes, interacting uneasily through confusing tales of morality and counter-morality. The one thing never confusing, though, is the way they’re dressed.

“All my dresses are beautiful. They gotta be in this racket. There’s nothin’ like clothes – that’s the sugar makes the flies come round.”

Isabel Jewell in Marked Woman

Even today, an audience knows immediately what to think of a character from the tacit codes Hollywood has dictated. Of course, the viewer has to be careful. That well-dressed sophisticate or trashily-clad hooker could be just dressing ‘down’ to send either the audience or their fellow characters down the wrong stereotypical alley.

Hollywood costume in the 1940s differed in one major way from its ‘equivalent’ in the real world. It was lavish. Despite wartime government guidelines, which were supposed to restrict studio fashion to being as non-theatrical as possible, ready-made and ‘favourable,’ designers such as Jean Louis, Edith Head and Adrian were having none of it. Characters from the highest echelons reigned resplendent in a different gown every scene; even the dullest housewife wore Dior versions of “bourgeois” and the lowest street bum glowed in his designer-ripped shirt. Film Noir may have been essentially B-stuff, but costume was one area in which even Budget Hollywood couldn’t stint.

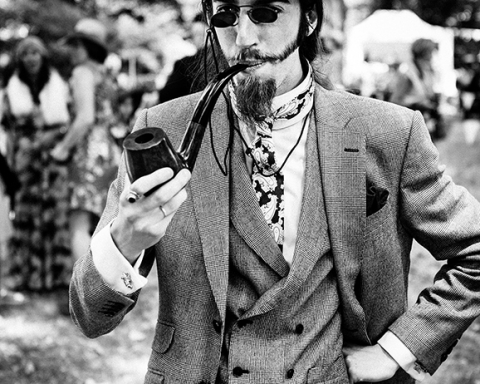

Men’s costume would, at first glance, appear to have drawn the short straw. The very best that male characters could hope for was just a variation of the male uniform, the business suit. Wide-lapelled, solid suits for the most part, though even they carry layers of code. A good jacket, ripped and torn, says something completely different to a cheap affair, however smart, even today. In men’s attire, just as much as those smouldering sirens that make up the majority of Film Noir’s women, the codes are strong. Robert Ryan’s Hawaiian shirts in Beware My Lovely come as quite a shock, just as much as the dapper sight of dangerous Ralph Meeker in Kiss Me Deadly. Not to mention the classy campery of Clifton Webb’s delicious villain in Laura.

Body and Soul shows the rise and fall of boxer John Garfield. As his social status grows, so do the size of his jacket shoulders. It is only fitting that by the denouement he has been reduced once more to a pair of satin shorts.

Jazzy ties designated a dandy even in the 1940s, despite received opinion nowadays about 1940s geometric neckwear; and what was worse, usually a dandy of the criminal persuasion, especially if it had a saucy picture of a scantily clad girlie in the lining. Smoking jackets carried a similar message. No one needs to have a smoking jacket, but no self-respecting noir villain would be seen dead without one (and was frequently seen dead in one) With Noir, the flashier the suit, the silkier the shirt, the more likely the body within was rotten. In a world that did not permit men to play the peacock, these garments were worn by gangsters or those ‘getting above themselves.’ Body and Soul shows the rise and fall of boxer John Garfield. As his social status grows, so do the size of his jacket shoulders. It is only fitting that by the denouement he has been reduced once more to a pair of satin shorts.

The use of coats in Noir makes a fascinating study in itself. John Garfield’s overcoat in Body and Soul is of the massive camel-hair variety. Humphrey Bogart’s sundry detectives are rarely seen sans trench coat. In an America so shortly out of the austerities of Depression and war, ownership of a coat was the ultimate luxury. No one had forgotten how recently they had been cold. Orson Welles made a great deal of overcoats throughout his film career – from the not-quite-noir Harry Lime in Third Man to the disgusting Hank Quinlan in Touch of Evil. It would not be flippant to say that a good part of Welles’ characterisation relied on his choice of overcoat in a movie.

Orson Welles made a great deal of overcoats throughout his career – from Harry Lime in The Third Man to the disgusting Hank Quinlan in Touch of Evil. It would not be flippant to say that a good part of Welles’ characterisation relied on his choice of overcoat in a movie.

The Sweet Smell of Success makes constant use of coats as symbols. Tony Curtis’ slimy PR man won’t wear a coat to the club because he can’t afford a tip for the hatcheck girl; something noted by Burt Lancaster’s equally obnoxious newspaper columnist. He, in turn, drapes his diminutive sister in a giant mink as a symbol of ownership, a garment she ultimately discards for a beatnik duffle when she leaves him for her sensibly wool-overcoated jazz guitarist.

Uniform in Noir is used and corrupted as required. Delivery boys real or false are often used as instruments of death. Murder by Contract, Destination Murder and While the City Sleeps all have murders by uniformed deliverymen, though other times they have a more benign presence – the elderly removal man in Kiss Me Deadly, for example. Taxi drivers, bar men, mechanics, musicians, all are seen, uniformed, in their place of work. We have to remember just how much uniform, and especially military uniform, was respected in mid 20th Century America. When it became defiled it was doubly shocking. William Bendix’s ex-marine in The Blue Dahlia puts the uniform and, by implication, the flag, to shame out of service, but Robert Ryan’s racist GI in Crossfire is doubly upsetting – he wears his uniform throughout.

Uniformed policemen in Noir are generally a comforting sight. Plodding, yet essentially on the side of good, the uniformed cop holds nothing to fear for law-abiding citizens. Not so his plain-clothed counterpart. Occasionally helpful (take Phantom Lady, for example, where a straight cop is so difficult a concept for us to handle today that I suspected him throughout, the first time I saw it) but more likely to be brutal, civvies only allow for non-detection of a bad apple in the LAPD barrel. Which brings me back to overcoats. Just check out Robert Ryan’s black manteau in the early scenes of On Dangerous Ground….

In the second part of this foray into Noir chic, I’ll be looking at women’s clothes in 1940s and 1950s B movies, lavishly illustrated for all the chaps, of course, with lots of pictures of cinema’s greatest Femmes Fatales.