You were born in Yorkshire. You’ve had lots of Yorkshire characters, but was your family steeped in Yorkshire from way back?

My mother and father weren’t Yorkshire people. We ended up there because my father was an engineer. It was during the Depression in the 1930s and he couldn’t get any work down in the south, so he ended up working first in Hull, then Leeds, and then he went to Sheffield towards the end of the 30s, where he found work with a company called Newton Chambers, who made lavatories and things like that. It’s gone down in the files, from some journalist, that they made lavatory paper, but that’s not quite right and I’m sure he wouldn’t like to have been remembered as a man who made lavatory paper!

Was there a point where you ever developed a Yorkshire accent?

You tend to pick up your accent from your parents, and mine were Oxford English, I suppose. But if I was with certain people I’d begin to pick up a Sheffield accent. But since then I’ve done loads of Yorkshire characters, in Ripping Yarns and so forth, and I realised I’m actually very fond of Sheffield, even though I haven’t lived there for 50 years. I think the place where you were brought up has a very strong influence on you; it’s bound to, as a lot of your first impressions all come from your first 20 years.

I once went on holiday with some friends from Leeds, and by the end of it, I was speaking Leeds.

I find that when I’m with Yorkshire people [breaks into broad Yorkshire accent] it’s lovely, I kind of get very easily into it… It’s a very comfortable accent, it slows things down. I mean Cockney’s all very quick, isn’t it? [breaks into Cockney accent]: out the back door, get in the van, off you go, you’re nicked!

Were you a natural performer at school?

Well yes, I was able to make up stories and characters. I remember when I was ten years old – it was 1953, the Coronation year – and I used to do a little ‘act’, “Michael’s doing one of his acts in the milk room”. And I’d just go in there and improvise a story about the coronation, things going wrong and that sort of stuff. It was a bit of improv, though I’m far too scared to do improv now. So I was able to make people laugh, and you gravitate towards other people with your sense of humour and you end up with a circle of people who are slightly subversive gigglers. I was a giggler, absolutely anything could set me off. There’d be some reading around the class and I knew the word ‘breasts’ was coming up and it would set me off. But also it was from watching other people, observing what was going on and how they moved and their gestures. I found I could reproduce it and people would say, hey, that’s brilliant, that’s just like Mr. Quinney. So you’re not just reproducing them, you’re putting familiar people in unusual situations, which is what comedy is all about.

When you first met Terry Jones at Oxford, did you immediately notice each other?

I made a very good friend on day one who wasn’t a humourist himself, but he loved Spike Milligan and Peter Sellers, but he also had an appreciation of theatre and that sort of stuff, which I didn’t have, and he pushed me towards acting. I first saw Terry in a production somewhere. He was a year ahead of me and he was quite well-known. The first thing that struck me was what a nice bloke he was. He had no airs and graces and, my God, there were plenty of people at Oxford who did, who liked to cultivate a slightly mysterious persona. So with Terry it was sort of love at first sight really. We had a similar idea of what humour could do and where it should go, mainly because we both liked characters; we both appreciated that comedy wasn’t just jokes. Terry has a great line in pathos. We did a play about capital punishment in 1964, which Terry and I and others helped write, and Terry played the condemned man throughout it. He could convey emotion, regret, sadness very well. It made me think, he’s the real thing, he’s not a poser – like me!

When you finished university, was there a period when you thought, what am I going to do now?

There was a definite period of ‘What am I going to do now?’ which has extended to the present day. At that time, I thought I was going to the BBC to be a general trainee, which was how people got into the BBC from university, and you basically end up in BBC management. But my heart wasn’t in it. I found I just wasn’t interested in the whole process of being interviewed. So I failed to get the general trainee-ship and I had to look around. A friend of a friend at Oxford said he knew these two guys who were writing a new television pop show but with more cultural content. They were looking for a bit of humour and a bit of fashion – would I audition? So I did and that was the first job I got after leaving university.

Was that called ‘Now!’?

Yes that’s right – with the very important exclamation mark. Well that kept me going for about six or seven months, during which period I got married, which was a reckless thing to do at that age. But I was working with Terry and he was employed at the BBC in the script department, so I used to go and help him write stuff. We ended up writing for the Frost Report, which got our names in front of people who wrote and acted, and that’s where we met all the other Pythons, in 1966. It didn’t pay anything, but I felt it was the way I wanted to go. The first thing that gave me some stability was Do Not Adjust Your Set, a 13-part series which I wrote with Terry and Eric Idle and appeared in alongside David Jason. That gave us enough money to feel more secure, then we’d do commercials or whatever came along, but we never really made much money until Python broke in America.

How difficult was it to pitch Monty Python’s Flying Circus to the BBC?

You can’t really audition comedy like you can interview someone who designs bridges or wants to work in the foreign office or something. You’ve just got to hope that somebody on that panel, or somebody somewhere, will just come out and say, hey, you’re great! That didn’t actually happen to us early on; it took quite a long time before we found people who were in a position of power who liked Python. The people who really liked Python were people like us of our age. Although one strand that was always very fond of Python was the music business. Groups loved watching it, perhaps they saw similar acts of rebellion in what we were doing through comedy to what they were doing, smashing guitars on stage and everything. We’re all trying to make a sound that is different.

Are you aware of the Chap Olympiad? It seems to be a combination of Upper Class Twit of the Year and the Silly Olympics.

Ah well, I might have to consult my lawyers! So what happens?

Everyone dresses up and takes part in things like Not Playing Tennis and Butler Baiting. One year only they had Shouting at Foreigners. They had a chap dressed up as a foreigner, wearing a fez, and contestants had to enter his shop and demand certain items.

That’s very Pythonic! We had a game show called ‘Prejudice’ where you had to decide who was the worst nation on Earth. It was hosted by a manic man who would probably be Nigel Farrage now. You had to find the worst name you could for a foreigner. Miserable Fat Belgian Bastard won. The most extraordinary PS to that story was that, I think it was Terry who met a Belgian and apologised profusely straight away for the jokes about Belgians, explaining that we don’t mean it. And this Belgian said no, you’re right – we are miserable fat bastards!

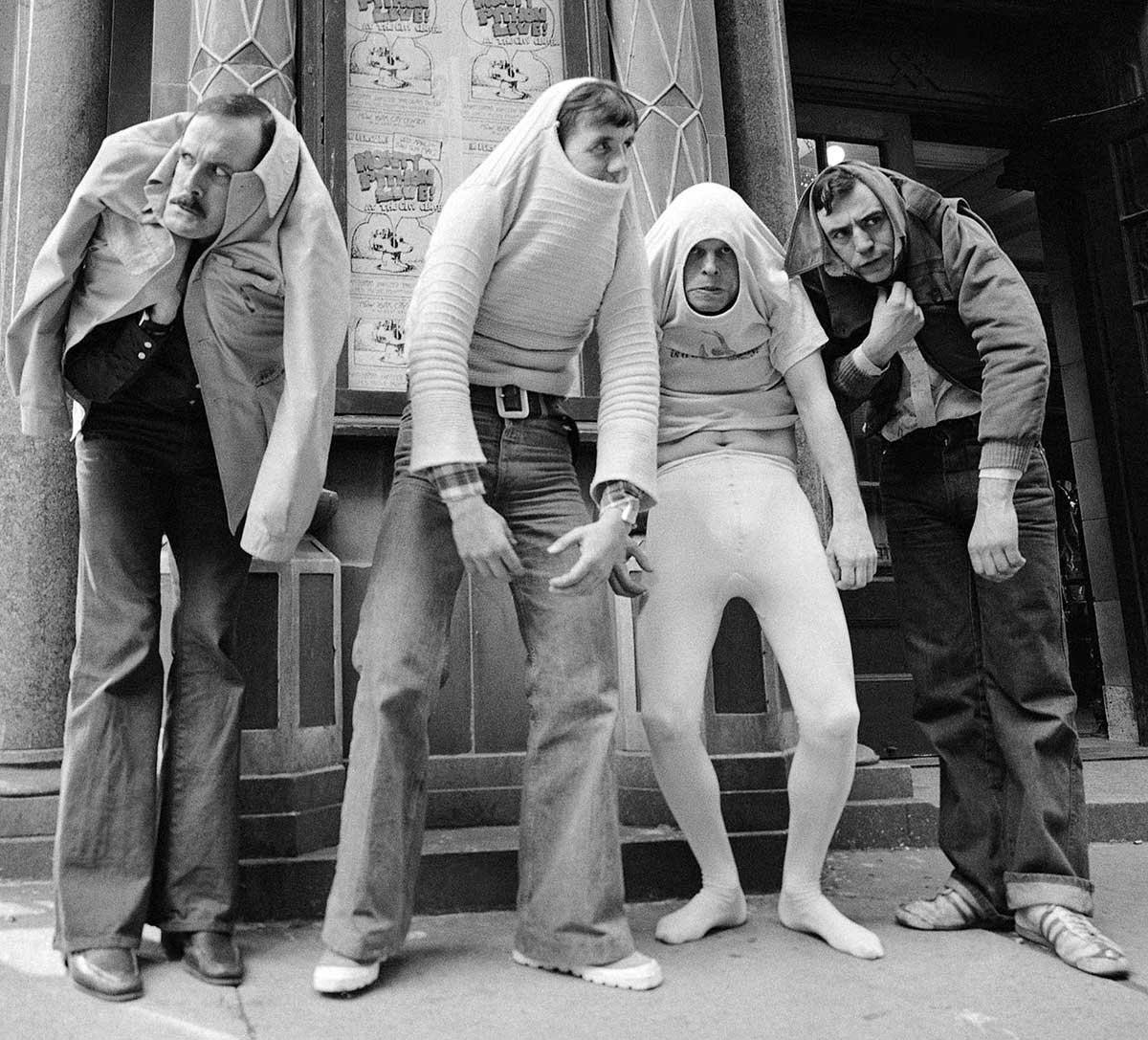

Where did the Gumbys come from?

He was a character who had these moronic views that were expressed with extraordinary force. The first Gumby was actually played by John, standing in a stream in gumboots [does Gumby voice]: “I’ve been standing in this stream for a week.” We had to decide what he’d wear, so he had gumboots because he was in a stream, then the knotted handkerchief on his head and a striped sleeveless sweater. From then on, I wrote most of the sketches so I tended to do the Gumby character.

Terry Gilliam had to play Gumby in the O2 show. It was funny seeing this director who had worked with Hollywood stars worrying about how to arrange the flowers as Gumby. In the end he did it so well we couldn’t get him off the stage!

A lot of stand-up comedy these days is just a bloke in a shirt on stage talking about his life.

Exactly – autobiographical and quite attitudinal. Pro-women, anti-men, or pro-men, anti-women. So many people say that Python created a whole new sense of humour, but I never saw that at all. People have been influenced by it, in the way we were influenced by the Goons, to take risks and do weirdly conceptual things, like having the television switch off in the middle of a programme, but we were just having fun with the medium. It was just mischief-making, really. Mischief is quite a difficult thing to pull off and you can’t export it to somebody else. There wasn’t actually a formula to Python at all. It was a universal silliness which they got in America, which might not work with something like Vic and Bob, for example. I think Python worked in America even though they didn’t understand what vicars were, or cricket, but I think they quite liked the fact that they didn’t. It was a certain time when television was becoming quite bland, so there was a lot to rebel against by watching Python. No commercial TV company would ever show it, so that’s why people were

enjoying it.

You went on to do Ripping Yarns after that. I suppose you took that Python silliness and put it into a more enclosed space?

Yes, Terry and I were very conscious that if we did something outside Python, it musn’t be like Python. So the 30-minute narrative was seen as a different format, but there were still quite a number of Python characters in there, but using them as part of a longer story. I remember thinking at certain times, I wish we’d written this for Python. We had some good actors: Denholm Elliott, Ken Collie, Roy Kinnear. But they didn’t quite understand; there was a short-cut to Python humour that all the Pythons absolutely got, so there was a certain amount of adjustment.

In Escape from Stalag Luft, the whole story hangs on him being the only one who wants to escape.

Yes, that was the one idea about that one. I was brought up on wartime escape stories, so I knew what the format was. One tough guy would come along, and all the others would go, yes, let’s do it! But somehow it didn’t convince me; there had to be another side to it.

I also really enjoyed the passing the port to the right scene in Roger of the Raj, which ends up with everybody going outside and shooting themselves.

John Le Mesurier was in that one. And a wonderful performance by Alan Cuthbertson, very British officer-like, who said, “I think women should be allowed to pass the port, and toss their hair, and flash their beautiful eyes…” It was a wonderful paean to women and their beauty, and at the end Lord Bartlesham says, ‘You know what to do’. And he goes out and shoots himself. That was a good example of how doing it absolutely straight delivers a much better laugh.

Interview by Mr B The Gentleman Rhymer

Read the whole interview in The Chap Summer 18 digital edition