Gustav Temple takes a highly educational sartorial stroll around the West End of London with professional city tour guide Russell Nash

We meet on the steps of the Athenaeum Club and head along Pall Mall towards the bottom of St James’s Street, where Russell pauses outside the fabled gables of London hatters Lock & Co. to tell us its history:

“In 1676, James Lock opened a hat shop very close to here. At the time, this area behind the Palace was being developed. Henry Jermyn, who had taken a lease on the land, developed it and the aristocracy started to move in, and with them all the services they needed. The current Lock & Co shop front dates from the early 1800s, one of the oldest intact original London shop fronts.

When a young aristo named Mr. Coke, wanted a hat for his gamekeepers, whose top hats were being knocked off by branches, he required something that would sit close to the head but also offer protection. So he came to Lock & Co in 1849 and they came up with a rounded hat, which they hardened using Shellac, made from beetles, produced by the Bowler Brothers down in Southwark. The famous story is that the Earl brought the new hat down on the pavement and jumped up and down on it to ensure it wouldn’t break. By the beginning of the 20th century they were making 60,000 Coke Hats a year.

JOHN LOBB

Inside the hushed, reverent room full of softly-lit cabinets displaying the finest men’s shoes ever created, Russell confides in me his theories about the difference between fashion and style: “In the fashion business, designers decide what they’re going to make and people buy into that. With bespoke, the customer is the designer. Unless you’re a rock star or a movie star, at these sorts of prices, most customers at Lobb will get fairly conservative shoes that won’t go out of fashion and can be worn every day. So what we see on display are your brogues, Oxfords, etc, but you can have absolutely anything made here, as long as you pay for it.” We notice a cabinet full of velvet Albert Slippers, and both agree that every gentleman should own at least one pair.

CROWN PASSAGE

At the entrance to this gas-lit alley off Jermyn Street, Russ pauses eloquently to quote Samuel Johnson, who said of London: “If you wish to have a just notion of the magnificence of this city, you must not be satisfied with its grand streets and squares, but must take full survey of its innumerable little alleyways and courtyards.”

When you come down Crown Passage, you really get a feel for what he meant. It still has gas lamps. There are about 1,600 gas lamps in this part of London, powered by mains gas operated by timers. Until 1980 they were all still lit by hand every night. There are still four full-time employees who maintain the gas lamps of London, who work for British Gas.

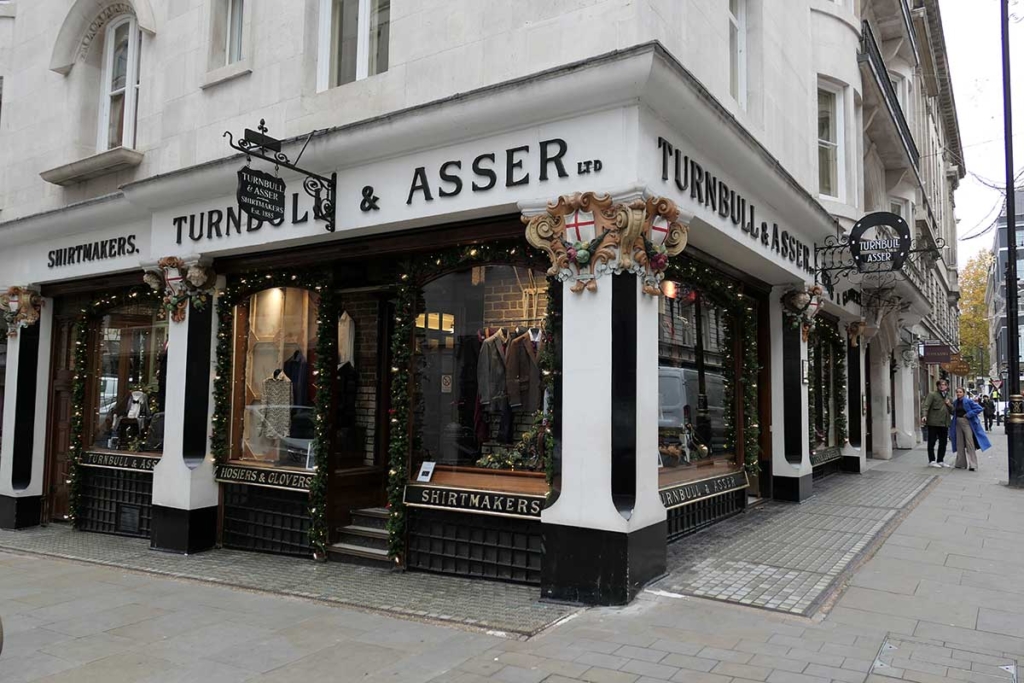

TURNBULL & ASSER

“This outlet on Bury Street has been Turnbull & Asser’s bespoke outlet since 1885; the main shop is up there on Jermyn Street. They have a minimum order of four shirts. Where these buildings intersect is where Beau Brummell’s grandfather William Brummell had a set of rooms that he let to aristocrats. Lord North came to London to take his seat in the House of Lords and took some rooms at William Brummell’s. Brummell asked him if there was any work for his son Billy. So Billy, father of Beau Brummell, went to work for Lord North and eventually became his chief of staff when Lord North was prime minister.

George ‘Beau’ Brummell was then reputedly born in a grace and favour apartment in Hampton Court Palace, went to Eton, and by the time his father died he was one of the 500 richest men in the country. His sister gave her inheritance to her two daughters as dowries, his elder brother set himself up as a country squire, and Beau Brummell spent his inheritance on the finest set of clothes he could find and set himself up in some rooms on Chesterfield Street, and launched himself on London society. He was tall, elegant and perfectly proportioned and it was said of him that, had he needed to, he could have been an artist’s model.

It was a time when tastes were changing; the French Revolution had happened; the Treaty of Alexandria of 1801, after Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Egypt, had brought the booty of war to London, mostly to the British Museum. Lord Elgin brought the marbles from the Parthenon, and people saw these well-built, classical, beautifully proportioned objects, and that became the standard of the day. The Napoleonic Wars also brought in a militaristic look, and a rejection of the French style. Brummell’s look was ordered, classical, post-revolutionary and British.

CLIFFORD STREET

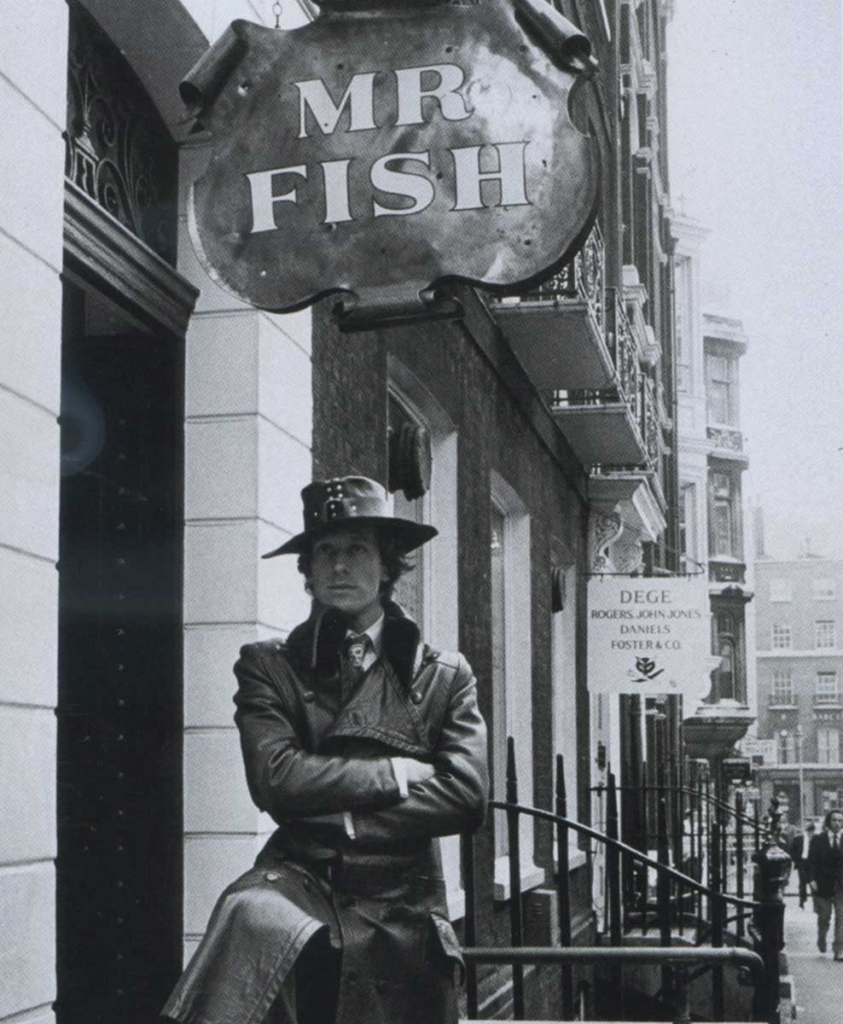

We leapfrog two centuries for our next visit, to Clifford Street on the edge of Savile Row, and the site of the premises of Mr. Fish.

“Mr. Fish was chief cutter at Turnbull & Asser and set up on his own with the backing of Barry Sainsbury. Turnbull & Asser had given him a lot of free rein to create more outré garments, which made him realise there was a market for them. But this was not the King’s Road; this was Clifford Street, the heart of Savile Row, with Bond Street and Dover Street nearby. So in the sixties Mr. Fish charged, from this shop, £100 a suit, the same as you’d have paid on Savile Row. Beau Brummell had famously said that a well-dressed man should not be noticed, but Mr. Fish now said, not any more.

Mr. Fish was very tied into the counterculture; he was a regular at the UFO Club. The press loved him for his slightly trippy, out-there way of talking, always good with the quotes. But he wasn’t actually selling to the hipsters; he was selling to those that could afford it. Savile Row was atrophying in the 60s, due to the fact that men no longer wanted to dress like their fathers. The other major difference was that a boy from the East End could now mingle with the aristocracy and it also worked the other way round, so members of the aristocracy wanted to dress more like the Rolling Stones.

Read the full article in CHAP Spring 20