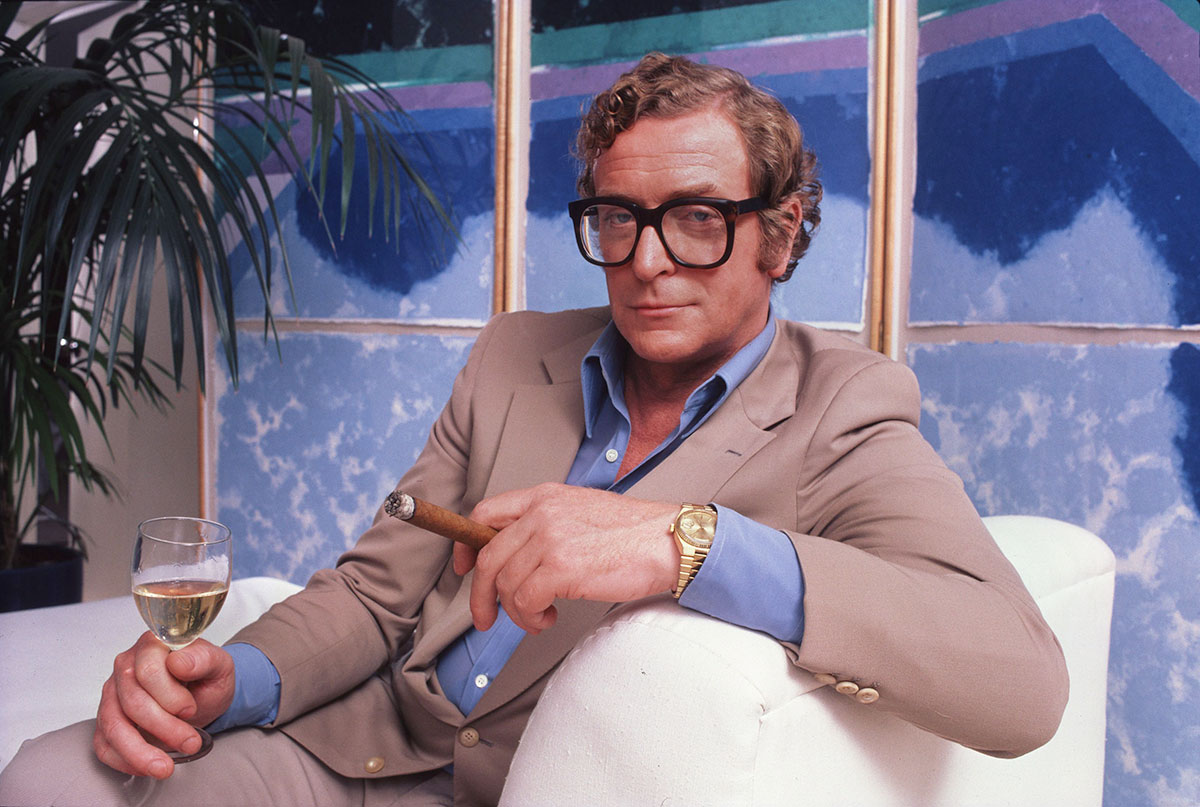

Colin Cameron touches the Douglas Hayward-constructed hem of the great British actor, to learn which of his films Michael Caine considers masterpieces and which ones he only made to fund some of his residences.

We know you as Sir Michael Caine, Oscar winner, but you began life as Maurice Joseph Micklewhite junior, which morphed into aspiring actor Michael White, under which name you began in repertory theatre, lasting a gruelling decade?

A brutal baptism, sometimes like purgatory. In this type of theatre, for those who did suffer from nerves, we had a bucket in the wings, which you don’t often get on a movie set.

What are the other main differences between theatre and film for you?

In the movies, you just do the take again, and again, and, if needs be, again, and again, and again. On stage, there is one chance and then plenty of time – up to two, three hours, maybe even longer – to ponder if you have fluffed the line.

How was the transition from theatre to movies after your big break came with Zulu, released in 1964?

The bucket in the wings for repertory theatre? I needed one of those for when Cy Endfield, Zulu’s director and an executive producer, told me I had the part because, even though my screen test was dreadful he thought there was ‘something there’. The rushes after we started filming weren’t great either, which is one of the reasons I never watched them on set. I mean, why worry about yesterday?

What about the craft of film acting compared to theatre?

The hardest thing for anyone making the transition from theatre to film is to avoid overacting on screen. Theatre is performance. Film is essentially, more often than not, just people talking. In the theatre you go to see drama, so there is no surprise that behaviour and speech is exaggerated. In the cinema that isn’t at all what is usually required, as it isn’t the case in real life. For me, the changes from the theatre direction was mainly to calm things down. To bring proceedings, filmed relatively close-up, back to reality.

Isn’t there the same level of intensity?

In film you don’t rehearse like you do in the theatre. In film, working together is usually more understated. What is almost always true is that the words are additionally precise. In the theatre, the audience has paid money and wants to be entertained. People who come to the theatre want to enjoy themselves, so the performance often expected is one that is more extreme. Of course, that brings pressure on the cast. Goodness me, in Glasgow, the balcony is netted off from the stage.

Have you always stuck rigidly to the script?

In California Suite (1978), written by Neil Simon and directed by Herbert Ross, my co-star Maggie Smith and I asked about whether we could ad lib. Herbert said, “If you are funnier than the script, why not?”. I had the same idea for Hannah & Her Sisters (1987). But in that case, the writer and director was Woody Allen. In truth, it’s hard to be funnier than him. In The Man Who Would Be King (1975), directed by John Huston, Sean (Connery) and I improvised a whole scene; the exchange that takes place in the plot’s court martial moment. With that, we were two stars so we asked John, could we work up something? John, who always directed me with a light touch – ‘from me you won’t get much direction; you get money instead’ – agreed on the basis that we had both been in the army for our National Service. He reasoned that we knew what sort of exchange two servicemen would have. And he was right.

How much advice from fellow actors did you take?

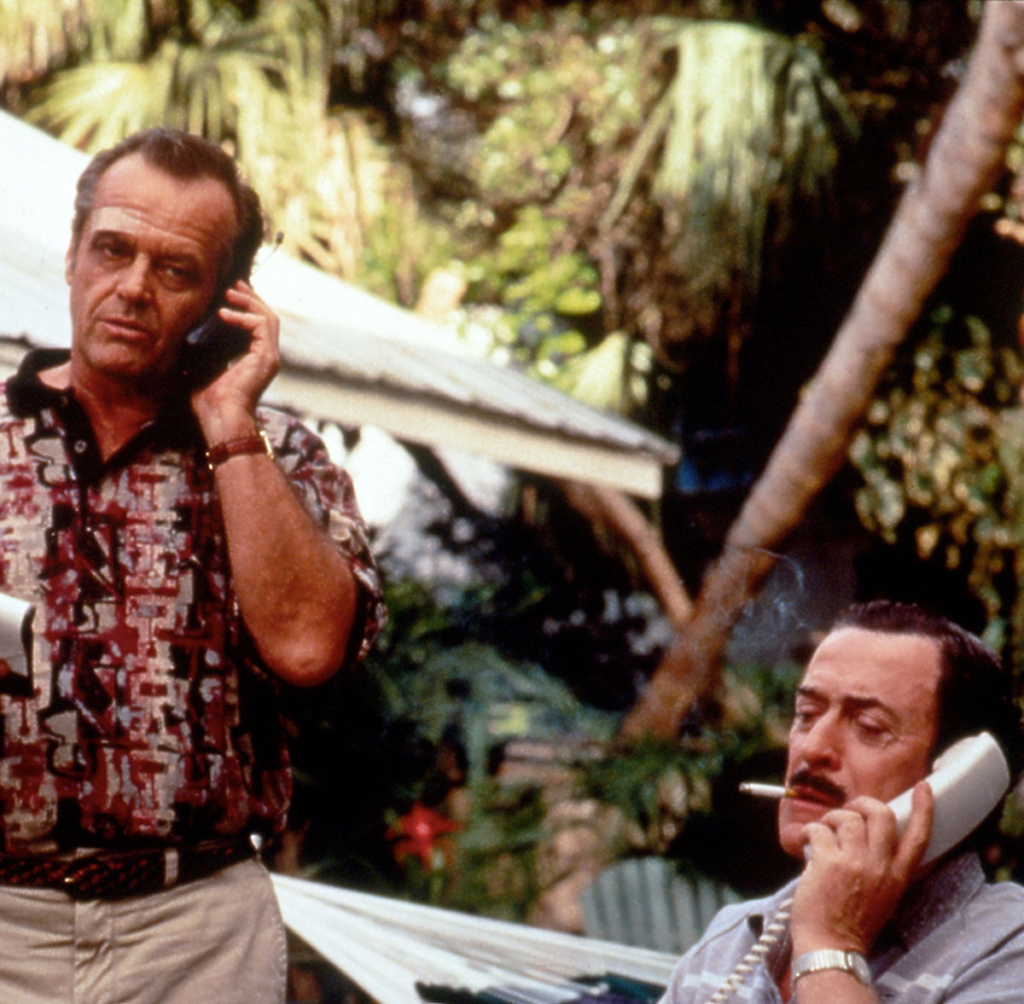

I listened to Jack Nicholson. He was behind me being cast as Victor Spanksy in Blood & Wine, released in 1996. Jack talked me into it, and out of semi-retirement. I’ve got a script, he said. Read it. Then do the film with me. It will be good fun. We’ll get paid, too.

Did any other actors, at the time more established and senior to you, offer counsel or prove to be inspirational?

I forget now from whom I have borrowed some of the tricks I have picked up over the years. They became a part of me. For Alfie (the 1966 adaptation of Bill Naughton’s novel and play of that name), when talking to the camera I was trying to use a method the late Sir Laurence Olivier uses in Hamlet for the soliloquies. And I owe Henry Fonda for a tip about which eye to use in dialogue to camera. We were both in a film called The Swarm in 1974. Henry said: ‘Don’t switch eyes while you speak or listen’.

So how you use your eyes on screen is key?

Mascara on my eyelids and pencil on my brows; in film you need your eyes. They have the creative power.

Beyond listening and observing, is it fair to say you’re unlikely to have many books by the likes of Stanislavski, Kazan and Strasberg, proponents of method acting, in your library?

I spend more time watching how people behave in real life. Do you notice that when someone is listening they don’t often blink? That’s a good example of how observation helps. It’s actually even more true when the person is talking loudly, or is genuinely angry.

Have you ever occasionally sought a little outside help?

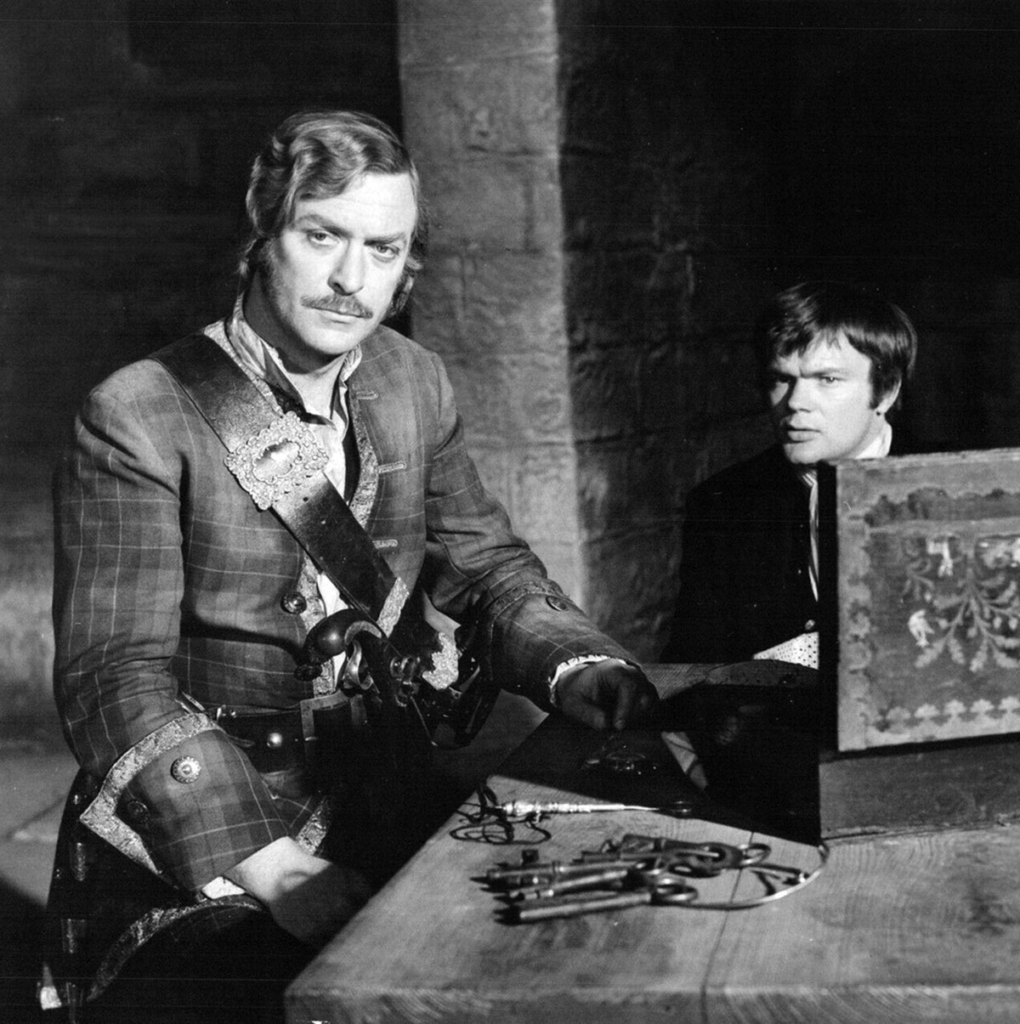

For the part of Jacobite Alan Breck Stewart in Kidnapped, released in 1971, my voice was at least partly based on listening to presenters on BBC Radio Scotland for a week. In California Suite, to play Sidney Cochran, Maggie Smith’s on-screen husband and a gay art dealer, I had a voice coach. But she was from New England, so some my dialect had just a little bit of home about it after we had finished. So it was helpful but made a bit more work ahead of filming.

Any more direct assistance?

I was in a film called Youth (2015), and had to conduct an orchestra. Of course I watched some of the best in the business at work, which was useful. But when we came to filming, I also used an earpiece linking me up to an experienced professional, off-stage, who could relay to me what I should be doing and, most important, what was next up.

Perhaps another career beckoned?

My sense was that the orchestra was following me, even though I was receiving instruction. The first violin – she said I was even better than the real thing!

I wonder whether we could prevail upon your comments on what you feel are your best films? EG The Italian Job (1969), “a sugar rush of entertainment” according to the critics?

Shot in Italy, co-starring with Noel Coward, so enough said.

The Quiet American (2002): in which your attention to detail was apparently key in securing an Oscar nomination?

Perhaps the best of mine. Perhaps…

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels (1988), a film that consensus suggests deserves ‘classic’ status?

Funny film, happy times.

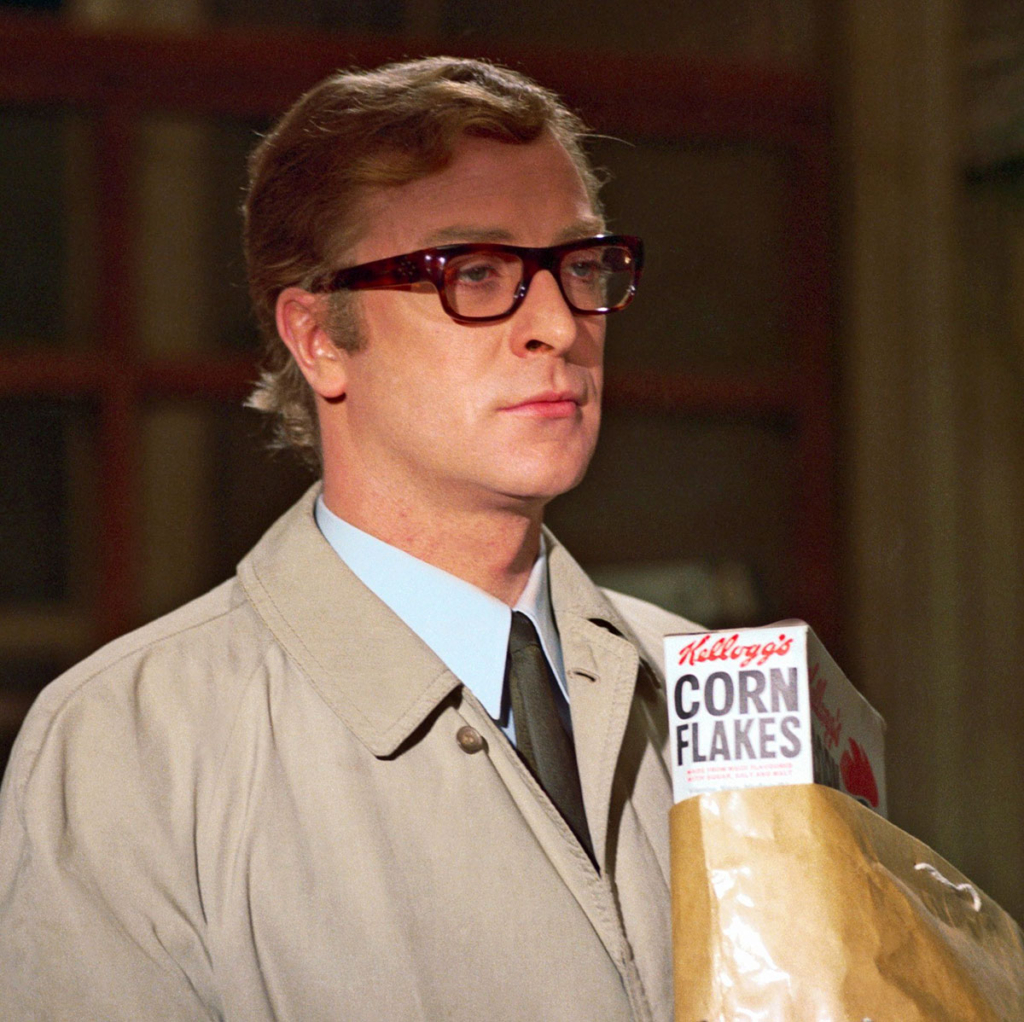

The Ipcress File (1965), reputedly the film that made you, and which was rich in “deadpan, lizard-like charm”.

I said that Zulu was my big break. The Ipcress File was also important with my name above the title. Harry Saltzman, who produced the movie, said, ‘If you didn’t think you’re a star, who else would?’

Hannah & Her Sisters, “an extraordinary, Oscar-winning performance”?

Good enough to win one, to be sure. Likewise The Cider House Rules in 1999. With Educating Rita (1983), The Quiet American, and Sleuth (1972), all good enough, along with Alfie for an Oscar nomination. Remember Alfie was a success in both Britain and the US, which was key for future roles. Plus the first Oscar nomination is very important, career-wise. I still love the movies, the variety and range of roles the business has offered me.

Have you ever been tempted to direct?

I always liked to finish work earlier than they do, generally.

So you have no regrets?

I think of the Rocky Graziano biopic, Somebody Up There Likes Me. I have been equally blessed.

This interview originally appeared in CHAP Winter 22