Michael Trubshawe’s entrance into the life of David Niven was as sensational as any of Niven’s stage or film entrances. Niven was stationed in Malta with the Highland Light Infantry between 1929 and 1931 as a very young officer. His reception by the other officers had been rather frosty – one refusing to speak to him all the way to Malta from Tilbury Docks. Once he’d acquitted himself on the cricket ground, things got slightly better, until one day:

“Suddenly, an ear-splitting belch rent the air. I spun around and perceived a truly amazing sight. Trubshawe was approaching. Six feet six, with legs that seemed to start at the navel, encased in drainpipe tight white flannels. He sported a blue blazer with so many brass buttons on it that he shone like a gypsy caravan on Derby Day; on his head a Panama hat with MCC ribbon; on his face the biggest moustache I had ever seen: a really huge growth which one could see from the back on a clear day. Part of it was trained to branch off and join the hair above his ears. It was in fact not so much a moustache as an almost total hirsute immersion.”

Niven immediately became close friends with this eccentric apparition, who went on to be his best man at both his weddings, and also accidentally introduce him to the craft of acting, as well as eventually becoming an actor himself.

Born Arthur Michael Temple Trubshawe on 7th December 1905 in Chichester, West Sussex, little is known about his early life. His exposure was entirely via Niven, once they’d become friends in Malta, and the interweaving of their subsequent lives is evidenced by the frequency with which Trubshawe enters Niven’s 1971 autobiography The Moon’s A Balloon.

‘This, old man,’ said Trubshawe, tapping a briefcase he was carrying, ‘is an invention of mine. It’s called “the dipsomaniac’s delight”.’ He flicked the lock and inside, set in green baize slots, I perceived a bottle of whisky, a soda water syphon and two glasses. ‘Come, let us drink to your most timely arrival with a glass of Scottish wine.’

Niven met many eccentrics throughout his career in the army and at Hollywood, but Trubshawe was always reserved for the top spot. In Malta, where he was often confined to barracks for unseemly behaviour, he kept a grand piano in his room, upon which he played 16th-century folk music. He’d entered the officer corps not in the usual manner via Sandhurst, but via Cambridge University, already marking him out from his fellow officers.

He compounded this distance on one occasion by fashioning a papier-mache helmet, to substitute for the heavy metal standard-issue helmet, unbearable to wear in the Mediterranean heat. “Can’t possibly wear the bloody thing, old man, it’s too heavy and red hot to boot, so I’ve had this little number run up for the occasion.”

The occasion was a parade in front of a new sergeant major so fearsome that Niven only referred to him as ‘the Weasel’ in The Moon’s A Balloon. At the end of the parade it began pouring with rain, and Trubshawe’s ersatz helmet simply dissolved on his head and wrapped itself around his ears. He was confined to barracks again, but Trubshawe got his own back by hiring a string quartet to play nightly in his room, which happened to be directly above the Weasel’s room. Trubshawe had a private income, like many other officers.

There was a shift in Trubshawe’s eccentricities when Niven returned to Malta after his first two month’s leave. The man had only gone and fallen in love, with a beautiful blonde named Margie Macdougall. Her Christian Scientist beliefs had put the kybosh on Trubshawe’s drinking habits. “Sinister cracks were appearing in the Trubshavian façade,” as Niven put it. “We should give up blood sports, old man. No more the chase, be it fox, stag or field mouse. Amateur theatricals – that’s something for us.”

And so David Niven entered the thespian world in an amateur troupe called The Hornets. Niven’s glittering acting career began in a series of sketches at the Colorado Canteen in the dockyards of Valetta.

In 1940 Niven married Primula Rollo at Huish, Wiltshire, with Trubshawe as his best man. Trubshawe himself opined about ‘Primmie’: “She was an absolute darling, the perfect English rose. She was kind, she was fun, and she was to be the most wonderful mother for the short time she was allowed. I didn’t think he’d ever really met anyone like her. She wasn’t at all like an actress, she was just the best sort of English girl of that period and one of the last of them; after the war women stopped being like that. Primmie was England in the 1930s: country cottages and small children and all that gentle, lost world of the upper classes at home.”

At the end of the War Niven and Trubshawe parted company, Niven to make his entrée into Hollywood and Trubshawe to open a pub, The Lamb in Hove, East Sussex. Niven looked up his old army chum when he was married for the second time (after Primmie’s untimely death) to Swedish model Hjördis Genberg in 1948. And when Trubshawe wasn’t there in person, Niven remembered him by attempting to insert his friend’s name into every film he made. He had Robert Coote’s character in A Matter of Life and Death renamed Bob Trubshawe. During filming of Wuthering Heights in 1939, director William Wyler was having none of it and refused to allow Niven to drop Trubshawe’s name into any of the dialogue. Niven got around this by having a prop man add Trubshawe’s name to a tombstone.

Michael Trubshawe himself went on to become an actor, when his marketing plan for his hostelry in Hove was unsuccessful – he placed signs on the roads in Brighton simply saying TRUBSHAWE HAS A LITTLE LAMB – 12 miles.

He got bit parts in Ealing comedies such as The Lavender Hill Mob and Private’s Progress, eventually landing a part as Weaver in the Guns of Navarone – which also starred his old chum David Niven.

However, according to Hjördis Niven, the friendship by then was not as it had been during their army days. Trubshawe did an interview in the 1950s with Sheridan Morley, in which he expressed his disappointment at the cooling of his friendship with David since the 1940s. “David never really wanted me to be an actor, and he had never gone out of his way to help me,” Trubshawe told Morley. “But now that we were together, purely by chance, he seemed almost embarrassed.” Niven recounted their meeting on the set of The Guns of Navarone rather differently: “He swiftly made a name for himself in television and one of his earliest screen appearances was in The Guns of Navarone – a lovely bonus for me.”

We are not here to judge why, or indeed whether, Niven had abandoned his former friend to his own destiny. We can only concur that the life of Michael Trubshawe deserves as much recognition as the life of David Niven.

THE THURSDAY CLUB

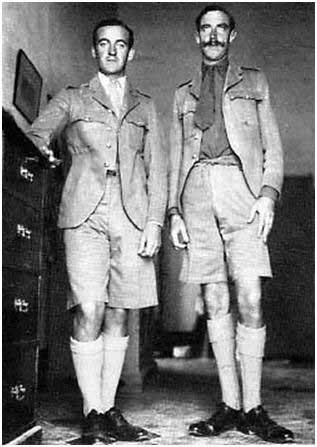

The only clue, surfaced quite recently and splashed about the red-tops, that Trubshawe was just as well connected as Niven is a photograph taken at Prince Philip’s stag do in November 1947 at the Belfry Club in Belgravia, a week before Philip’s wedding to Elizabeth. Philip had been a member of the Thursday Club, a men’s eating and drinking group dedicated to ‘Absolute Inconsequence’ who gathered at Wheeler’s fish restaurant in Soho. Trubshawe’s moustache can clearly be seen looming above his well-heeled chums’ heads in the middle of the photograph.

What a great article. I always wear a huge smile when I watch an film with Trubshawe in it.