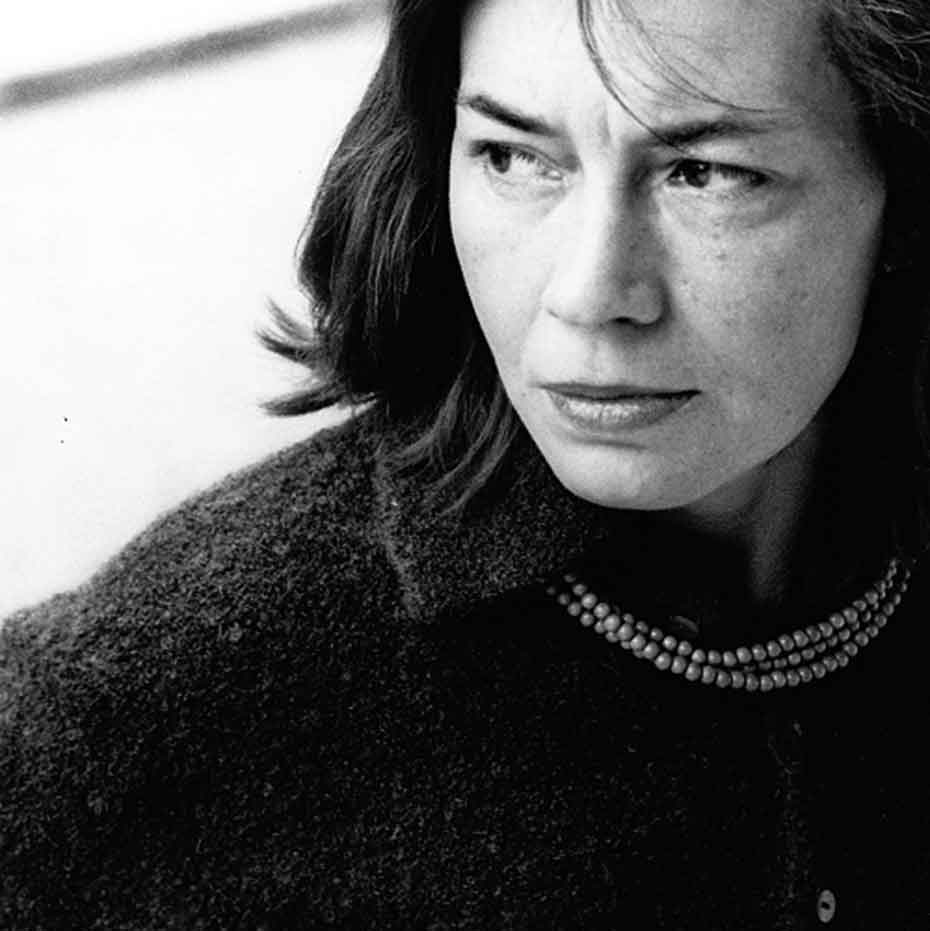

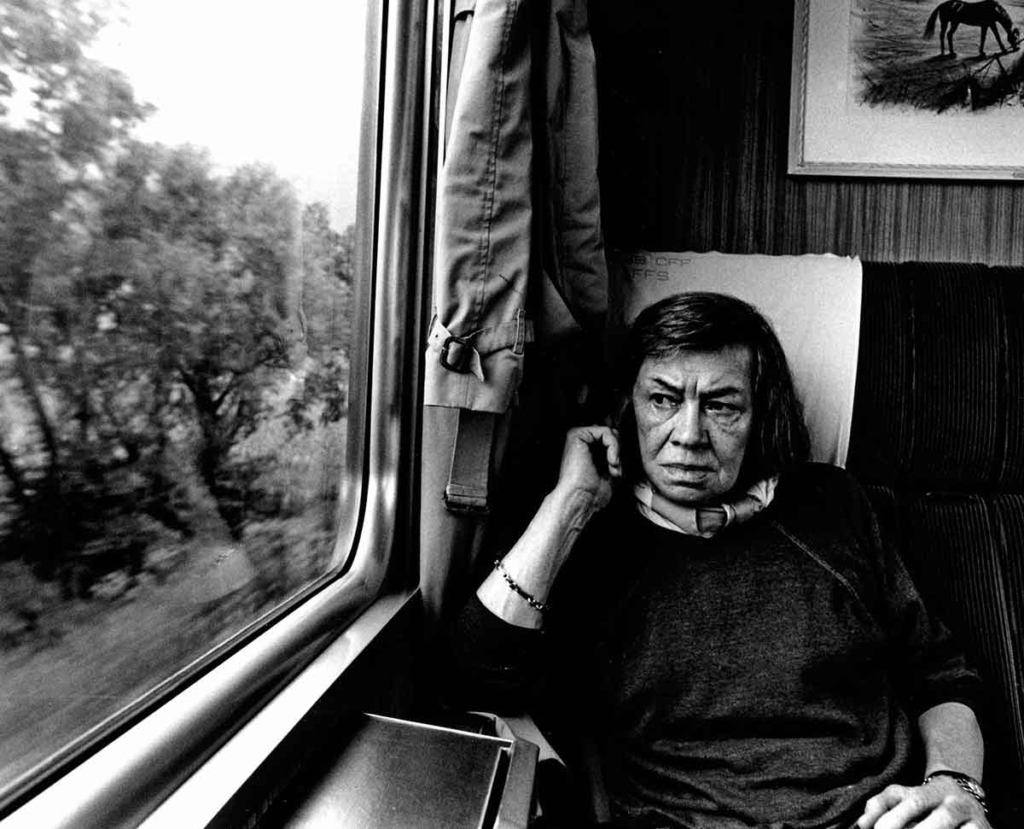

In the centenary of her birth, Gustav Temple provides a top five reading list for Patricia Highsmith, plus a reader advisory warning.

This year marks the centenary of the birth of Patricia Highsmith, born on 19th January, 1921 in Fort Worth, Texas. It is impossible to guess how she would have reacted to recent political events in her native United States, but she most likely would have expressed a skewed, complex, controversial opinion that neither blessed nor condemned either the incoming or the outgoing president.

Highsmith would certainly not have subscribed to the prevailing view of right triumphing over wrong, democracy over tyranny, good over evil. The appeal of her fiction is that her characters occupy a moral sphere completely distinct from any other. There is no moral compass in her stories; there is not even a moral wind sock. None of her characters ever learns anything useful, and none even comes close to any form of redemption. But Highsmith’s moral code isn’t simply a reversal of the Biblical notion of good and evil, which would not make for compelling reading.

Highsmith’s characters take decisions throughout her stories that seem random and fatalistic, guided by impulses that make no sense and usually lead them to catastrophe. However, they are not simply books about mad people; not all of them, anyway. The characters are much easier for the reader to identify with than the psychopaths created by other writers, who are usually set at the opposite end of the typical reader’s moral spectrum. We’re not talking Hannibal Lecter here.

Highsmith lays out her characters’ actions in a way that seems entirely convincing, even if a murder is committed (it usually is). She draws the reader so deeply into a journey into the protagonist’s mind and their circumstances so that, by the time the killing takes place, it seems like the only logical thing to do. You start the story thinking, ‘this chap’s a bit weird’, but by the middle of the story you find yourself egging him on in whatever foul deeds he has plotted. ‘Go on,’ you think, ‘push the car over the cliff, no-one will ever find out’.

The murder itself is always described in Highsmith’s flat, matter-of-fact prose, with as much emotion as she describes the way the murderer fills his car with petrol. By the concluding events of one of her grisly tales, the reader has somehow forgotten the sense of right and wrong they might have had before delving into the novel, and the nasty, scheming miscreant at the heart of it has somehow become the hero of the day. Highsmith’s fiction is a kind of persuasive, creeping seduction of the reader. In real life, this is exactly how she operated as a lover, using entreating letters, well chosen gifts and veiled threats to persuade someone (usually completely unsuitable) into her life.

Patricia Highsmith spent most of her adult life in exile from her native America. Her books sold in much greater numbers in Europe than in the US, where she was too closely bracketed as a writer of crime fiction to reach a wider, more literary audience. She had grown up reading European and Russian literature, and saw European tastes as more sophisticated. European audiences and publishers took her more seriously as a writer and she felt they viewed her, rightly, as the author of literary fiction. Most of the early adaptations of her work into films came from Europe; American audiences had to wait until after her death to see a version of The Talented Mr. Ripley that didn’t have subtitles.

Highsmith’s literary estate is held in Switzerland, where she lived until her death in 1995. Consequently, the America she portrays in her books is the country she left behind in the 1950s, preserved in aspic: an America of dime stores, telephone booths in diners, seedy boarding houses, roadside motels.

Some of her stories are set in other countries, each a fragment of Highsmith’s own travels. The reader delving into her entire oeuvre in sequence can track her journeys to Tunisia, Mexico, Greece, Venice and England, with her final, posthumous novel being the only one set in her adopted country of Switzerland. Anyone wishing to read about her life in full is strongly urged to read Beautiful Shadow by Andrew Wilson, the first biography of Highsmith, published in 2003. A subsequent biography, The Talented Miss Highsmith by Joan Schenkar came out in 2009, but for my money it pales in comparison to the first. Being the centenary of her birth, it will be a very Highsmithian year, with a new series of all the Ripley novels beginning this year, starring Andrew Scott in the lead role, a film based on her novel Deep Water and the publication of a third biography by Professor Richard Bradford, Devils, Lusts and Strange Desires.

Some of her novels are much better than others. With Highsmith, it isn’t a good idea simply to pluck one of her books at random, as one might with Agatha Christie or PG Wodehouse, and expect it to be typical. Some guidance is required, and here I offer the suggested reading list for Patricia Highsmith

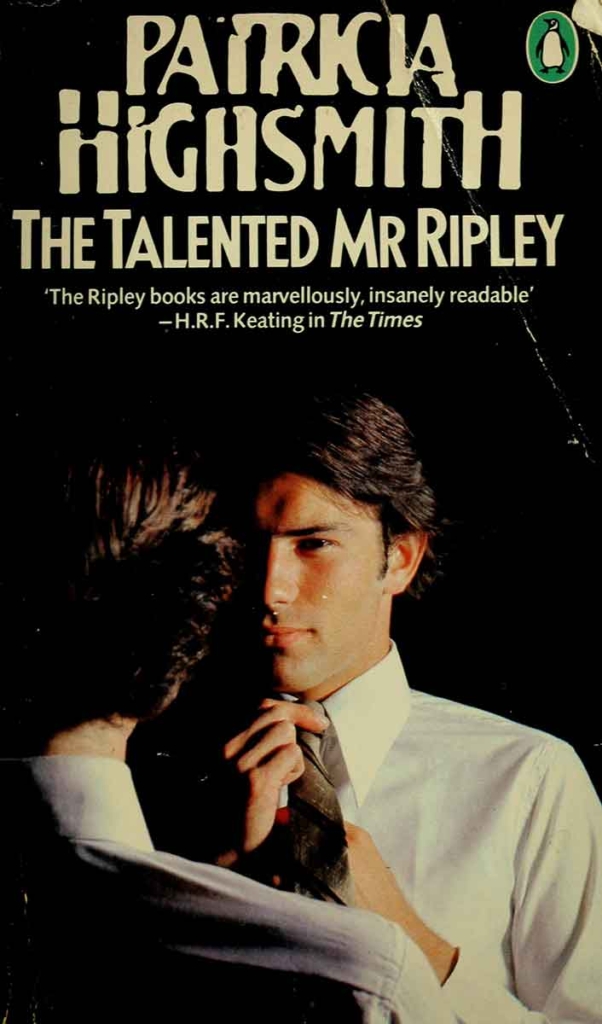

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1955)

We’ve all seen Messrs Law and Damon frolicking around in Italy with Miss Paltrow in Anthony Mingella’s excellent 1999 adaptation, and the book is still the best Highsmith to start with. There is a reason for it being the most adapted of her novels, and that is the main character of Tom Ripley, about whom she went on to pen four further novels, all of which are superb. But you have to start with Talented…, because it is in this tale that Ripley’s true character is formed, and in which his talents for mimicry and forgery, not to mention his fearless chutzpah, are all developed when given the opportunity. Highsmith herself so identified with the murderous sociopath that she often signed photographs with his name rather than her own. Her close friends thought she was secretly in love with Ripley, in itself a glimpse into her skewed view of her own creations.

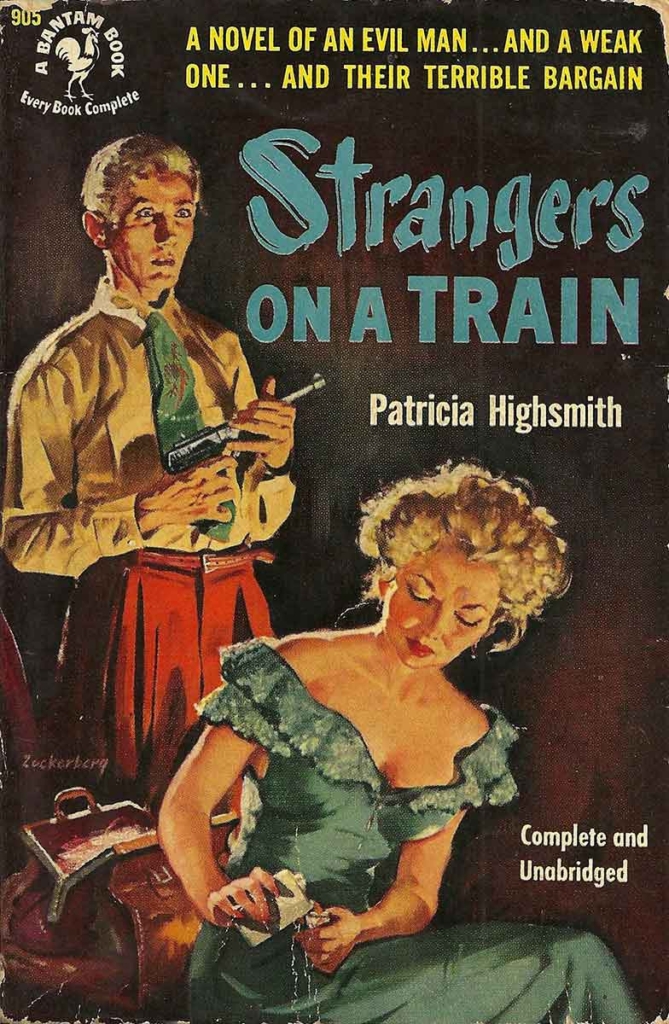

Strangers on a Train (1950)

Highsmith’s cri de coeur, and an extremely accomplished work for a first novel, setting out all the themes she would return to again and again in her fiction: the seemingly perfect crime – two strangers agree to swap murders – gradually falling apart when one of the murders goes wrong, and one of the murderers turns out to be far more mentally unstable than the other; the notion of everyone having their ‘shadow’ following them around, an amoral version of themselves who can lead them into darker territory if allowed; the battle of conscience that develops, beginning with the conviction that a terrible act is justifiable and the sense of guilt that gradually arrives afterwards. Even Hitchcock, however, changed some of the darker elements of the story for his 1951 adaptation, removing some of the homosexual undertones between the two main characters.

This Sweet Sickness (1960)

A great one to start with if you prefer to read a book without the shackles of pre-existing cinematic images. It isn’t surprising that it was only ever made into a forgotten French adaptation in 1977 with Gerard Depardieu, as the protagonist lacks the panache and gutsy appeal of Ripley, though is equally compelling as a character. David Kelsey lives a double life, one in a seedy boarding house in a small town, the other in a lavish country house that he is preparing for the arrival of the love of his life, Annabelle – who knows nothing of these plans for her future. In fact, she is happily engaged to another fellow and does not take kindly to Kelsey’s gradually more obsessive overtures. In today’s society Kelsey would have a restraining order slapped on him immediately, but in early 1960s America the term ‘stalker’ wasn’t common currency. When prying eyes start to peer at Kelsey’s double life, the body count starts to pile up, while he doggedly clings to his fantasy, refusing to believe that anything or anyone can stand in its way, even Annabelle.

Deep Water (1957)

Vic is unhappily married to Melinda, who carries on with a string of other chaps right under his nose, while Vic takes solace in his collection of living snails in the garage. So far, so Highsmith (she was an avid snail-fancier herself). This classic Highsmith tale portrays a domestic hell in seemingly stable suburbia, as if for any married couple to live happy together were a ridiculous chimera. Vic graduates from snide remarks from the sofa, behind his perpetual G&T, to rather nastier solutions to his wife’s infidelity. There is a film adaptation coming soon, directed by Adrian Lyne and starring Ben Affleck, though it will be interesting to see how such an unpalatable portrait of middle America is rendered for a contemporary audience.

The Tremor of Forgery (1969)

Set in Tunisia, this is the only of her novels in which Highsmith lays bare her frankly ‘difficult’ political views. But the main events of the story are described with typical sangfroid, and it is an excellent example of Highsmith’s ability to have her characters stumble into the most awful life decisions as though they have no choice, and to transform an initially comfortable setup into a complete and hopeless mess. It also displays her talent for creating minor characters who are as convincing as the protagonists, and showing that some casual friendships are actually a seething cauldron of resentment and hatred never truly expressed. The actual murder, taking place near the end of the story, provides only the icing on a cake layered with the complex relationship between three drifters mooching about in the expat quarter of Tunis.

So delighted to find you!