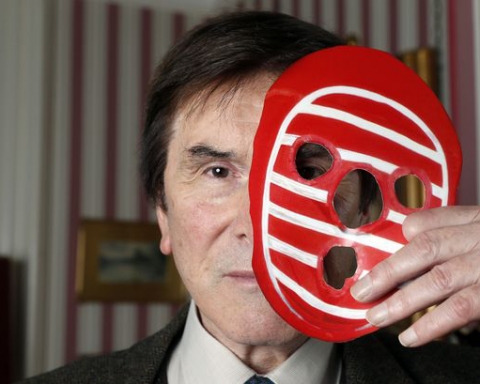

I am seated in a dimly lit room on a comfortable white leather cushion, wearing a pair of headphones. There are five other people in the same position in the room, and a seventh leather cushion against the rear wall – but this one is red. Into the headphones a soothing voice tells us to relax our bodies and allow all thoughts to float away from our minds, for we about to take part in a Zen meditation session with Kendo Nagasaki. Just as we hear that name, there is a shuffling at the door and it is opened by Mr. Lawrence, a middle-aged Englishman wearing Japanese ceremonial robes and a stern expression. He moves aside to allow ingress to another figure: also wearing Oriental ceremonial robes, but slightly better ones, this person’s face is entirely covered by a black and red striped mask that fits tightly around his head. He bows to us all, and we awkwardly bow back from our leather cushions. The masked man seats himself on the red cushion and assumes the meditation position. The rest of us wonder what the hell we’re doing there; at least that’s what I do.

I have come 250 miles to a stately pile in Staffordshire to attend a weekend meditation retreat with Kendo Nagasaki. The last time I was aware of this man was in 1975 when I was 10 years old; on TV I watched him leap into a wrestling ring and promptly dispatch his opponent in a few theatrical rounds. He was wearing a similar mask back then; his whole image was based on Japanese Samurai warriors and, compared to the other wrestlers on the circuit – Big Daddy, Mick McManus, Giant Haystacks – to a 10-year-old kid, Kendo Nagasaki was nothing short of terrifying. Naturally, like 14 million other Britons, I was glued to the set for the ceremonial unmasking of Kendo Nagasaki in 1977.

The unmasking was a piece of televised ritual, eagerly anticipated by all Saturday afternoon wrestling viewers who wanted to know what this mysterious masked man actually looked like. After a bit of pomp in the ring by Gorgeous George, Kendo’s camp manager, the mask was removed and ceremoniously burned in a Japanese fire bowl. The man behind the mask was a young, handsome, European-looking fellow but there was something very peculiar about his eyes. He stared into the camera and the eyes seemed to be burning out of his face. His head was shaved except for a pony tail trailing from his skull, and on his crown was a red and green tattoo that looked kind of mystical. In short, Kendo Nagasaki was just as scary without his mask.

Little did I know that, 35 years later, I would be sitting in a room meditating with the man, that he would still be wearing his mask, and that I would still be slightly scared of him. Kendo Nagasaki never speaks and is never seen in public without his mask. He began studying Zen Buddhism long before his entry into the world of British wrestling, having had a successful career in professional Judo before that. He retired from wrestling in 1993 and went on to found the Kendo Nagasaki Foundation, a spiritual retreat in Staffordshire set in a huge old house with grounds landscaped into a Japanese meditation garden.

Since 2014, Kendo has invited small groups of guests to spend the weekend at his retreat to study Zen Buddhism. For me, there was nothing about this invitation that could possibly be declined. I already had an interest in Zen, like anyone who read Jack Kerouac in their youth, and I had attended a Zen retreat before, in London in the 1990s. But that was with a Japanese master and involved 5 hours of back-breaking meditation a day, starting at 5am. The schedule at Kendo’s retreat, as we were explained at 10.30 on Saturday morning, was much less punishing. Our hostess was Roz, Kendo Nagasaki’s personal assistant and his voice to the world outside his mask. Kendo never speaks or removes the mask in public and has never given an audible spoken interview.

Roz outlined the day’s timetable. There would be two activities before lunch – a meditation session and a singing bowl performance by Kendo himself. Her description of the day’s menus produced more reaction among the 12 guests than any of the activities, especially when apple crumble was mentioned. Roz left us to go and prepare the first activity, so naturally we mingled.

Or at least I mingled, introducing myself to some of the guests. They didn’t need any introductions to each other, for it transpired they had all been there before, some of them several times. One lady declared she had not missed a single event at Kendo’s retreat since they first started two years ago. She offered to show me some of her nine tattoos – all Kendo Nagasaki related, one of them replicating the one glimpsed during his unmasking ceremony, though not on her skull. Some wrestling programmes from the 70s were handed around; the talk turned to various fights at which Kendo Nagasaki had been victorious, and other more recent events at which the guests had been photographed with him.

The penny dropped. These people weren’t here to study Zen Buddhism; they were here to worship their wrestling hero. They were here to bask in his fame, not his Japanese garden.

After the first meditation session, we were led into the main temple for a performance of singing bowls. Seated on comfortable chairs before a table laden with copper bowls, the lights were dimmed and once more Mr. Lawrence swished in, followed by his master. I was seated right behind the tattooed lady, and scrutinized the markings on her upper back while Kendo pinged and clanged his bowls with a wooden stick. I saw Chinese characters and portraits of the masked wrestler while the sounds of the bowls howled around the room, and realised I wouldn’t get much out of this if I focused too much on the fans. There was something so Little England, so Suburban and so un-Zen about this place, so far, but I wondered whether a different approach would yield more benefits.

Fortified with tea, coffee and biscuits served from large urns, we were then taken on a walk through the Japanese garden, along gravel paths which Roz explains represent our journey through life. The paths are dotted with countless Buddha statues, wooden seats and an ornamental pond full of carp. We come to the Tree of Souls, an enormous yew with a plaque before it and a ceremonial wooden arch. Roz explains that this represents all the departed souls of the earth, whose wisdom we can share simply by placing a hand on the tree. “Would anyone like to share the wisdom of the dead?” She asked. The souls of the living hunkered down into their kagoules in the November drizzle. No-one stepped forward. To break the awkwardness I marched forward and bowed in the arch, touched the tree. The feeling of acute discomfort and absurdity was more powerful than anything the tree had to offer, but it encouraged others to follow suit.

The day panned out with further activities, punctuated by frequent visits to the refreshment area, where more wrestling conversation took place among the munching of custard creams. Apart from their passion for wresting, another similarity struck me about all the guests I spoke to: they have either been very ill themselves, or have a family member who is disabled or ill. The lady with the tattoos was severely depressed when she first attended two years ago; now she was a bubbly, happy soul who was keen to show me photographs on her phone of her bedroom at home, which was filled to the brim with Kendo memorabilia. I began to feel some of the guess circling around me; intrigued, perhaps a bit suspicious of my motives, since I clearly knew practically nothing about wrestling. They clearly want me to understand their host and report him favourably in the press. A large, walrus-moustached man called Lofty offered to lend me his DVD copy of and Arena documentary from 1988, which features the only interview Kendo has ever given.

The second day was Remembrance Sunday. The day’s activities commenced with a ceremony at eleven minutes past eleven. The radio in the Japanese temple was tuned to receive the broadcast from the Cenotaph. We all stood in two lines around Kendo for the two minutes’ silence. I was beginning a cynical train of thought about how, for a man who never speaks, two minutes’ silence will be a doddle, when the chimes of Big Ben rang out – sounding remarkably similar to the chimes of the singing bowls we had heard the previous day. Those two minutes’ silence were the first time during the weekend that I had been truly absorbed in the moment.

When I opened my eyes and glimpsed Kendo bowing after the chimes of Big Ben, I saw that Kendo Nagasaki stood for something even more complex than the odd admixture of Zen and wrestling. It entirely wiped out my cynicism, and after that it became easier to accept his weird masked silent presence. What had launched his wrestling career as merely a gimmick has clearly served him well. He is the only surviving British wrestler from that generation who has extended his reputation well beyond the ring. I did wonder, though, how many of his guests would be there if their host wasn’t Kendo Nagasaki – if, for example, the weekend had been hosted by a Japanese Zen master – and it seemed clear that they wouldn’t.

After dinner everyone retired to the communal living room and relaxed as they probably would at home; some sat around in dressing gowns, others sank tins of lager while watching Midsomer Murders. I went to my room to watch the Arena documentary on my laptop. It concludes with a hard-won face-to-mask interview with Kendo, in the back of a limousine in an underground car park. Lloyd Ryan, his then-manager, snatches away the interviewer’s microphone and it is broadcast with subtitles, the muffled voice of the subject only just audible. He turns out to be a thoughtful, insightful, articulate man, answering every question carefully and wisely in the third person. Though his real name isn’t mentioned, it becomes clear that this is an interview with Peter Thornley, who is merely the channel for the character of Kendo Nagasaki

On why Kendo always wears the mask, he replies: “I think people are trying to escape from reality, into another world or fantasy. Nagasaki is the perfect vehicle because there is no face. So you could actually put any face behind that mask. And you can give it any features, any character you want. You can put your own face behind the mask. So he works for everybody.”

I rejoined the others in the living room and watched the end of Midsomer Murders, idly plotting out a whodunit about this retreat with Ray, a professional crime fiction writer. The Samurai sword on display in a cabinet would surely have to be the murder weapon? I also wondered whether my fellow guests were such devoted fans that, had Kendo Nagasaki offered weekend retreats of watercolour painting, pottery or knitting, would they have still attended? I think so. This is not to denigrate them, or the whole retreat itself. If it takes a masked wrestler from the 70s to introduce, however briefly, a spiritual practice that seems to help people in some way, perhaps even towards healing whatever wounds they are carrying, then Kendo Nagasaki is a force for good. His estate has acquired a neighbouring building, which the Kendo Nagasaki Foundation has turned into the Lee Rigby Foundation for forces veterans and bereaved families. Lee Rigby was the soldier who was murdered in Woolwich in 2013. Any question that Kendo is merely feeding his ego and his pocket by hosting the Buddhist retreats is laid to rest by this development (especially as the cost for the weekend was remarkably cheap). Guests at the retreat are offered a tour of the Lee Rigby House and most make a donation to the charity.

There is no doubt that my weekend at Kendo Nagasaki’s retreat had an effect on me, and not just from the first-class apple crumble (which we were eventually served at lunchtime on Sunday). The last activity I took part in, before leaving early for the 4-hour drive home, was an extension of the singing bowl performance. We lay on comfortable mattresses on the floor with blindfolds, while Kendo clanged his singing bowls so we could feel them reverberate through the wooden floor. I could feel myself drifting into a state somewhere between being awake and being asleep. There was definitely something you could call peace in that place.

For further information about booking a retreat, visit kendonagasaki.org