On the bicentenary of Sir Richard Francis Burton’s birth, Chris Sullivan gallops through the extraordinary life of the notorious explorer, soldier, translator, writer, cartographer, orientalist, ethnologist, spy, diplomat, poet, geographer, expert fencer and sex obsessive.

Can you imagine that, in the not too distant past, a thoroughgoing rogue might stand up in his club in the Haymarket and, after far too many whiskeys, pronounce that he was off to discover a country and, even though I’m sure that those who lived in said country knew of its existence, he would be applauded, funded, sent off amidst fanfare and acclaimed a hero before he even set foot on the boat.

One such voyager was the unreservedly splendid Richard Francis Burton: notoriously unhinged, incredibly mercurial and enormously controversial, he was not usually welcome in a respectable Victorian household. He drank like a drain, smoked marijuana, imbibed opium and was blamed by associates of Algernon Swinburne for leading the poet amiss, precipitating his alcoholism and his obsession with the writings of the Marquis de Sade.

Burton was also uncommonly bright and extremely prolific, publishing 43 volumes on his explorations alone. He spoke 29 European, Asian and African languages and penned books about falconry, travel, fencing, human behaviour, sexual mores and ethnography. He translated and published some 30 works including an unexpurgated version of the Kama Sutra, The Perfumed Garden (the Arab Kama Sutra, basically) and The Arabian Nights. To publish some of his more excessive tomes and avoid prosecution, he formed, with Forster Fitzgerald Arbuthnot, the members-only Kama Shastra Society. Each of these works was sold subscription-only, with a guaranteed 1000 print run.

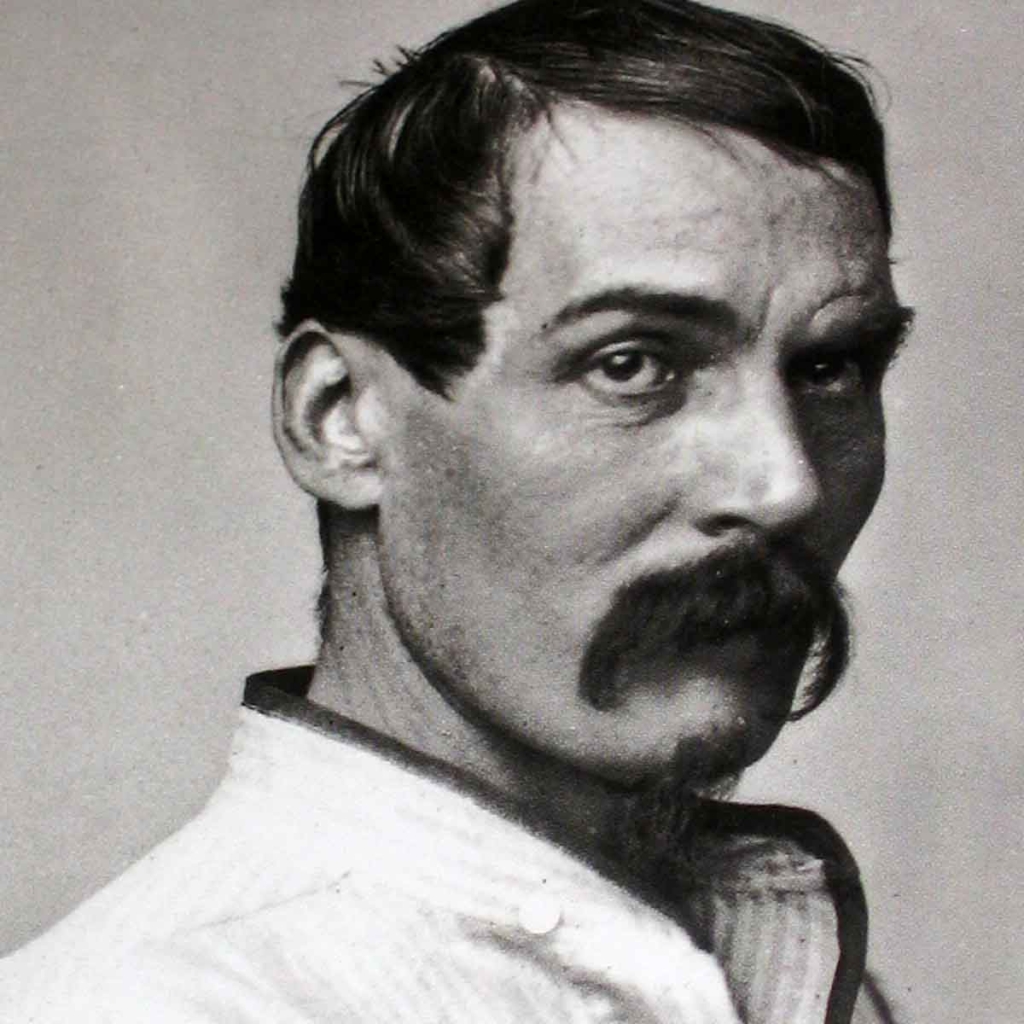

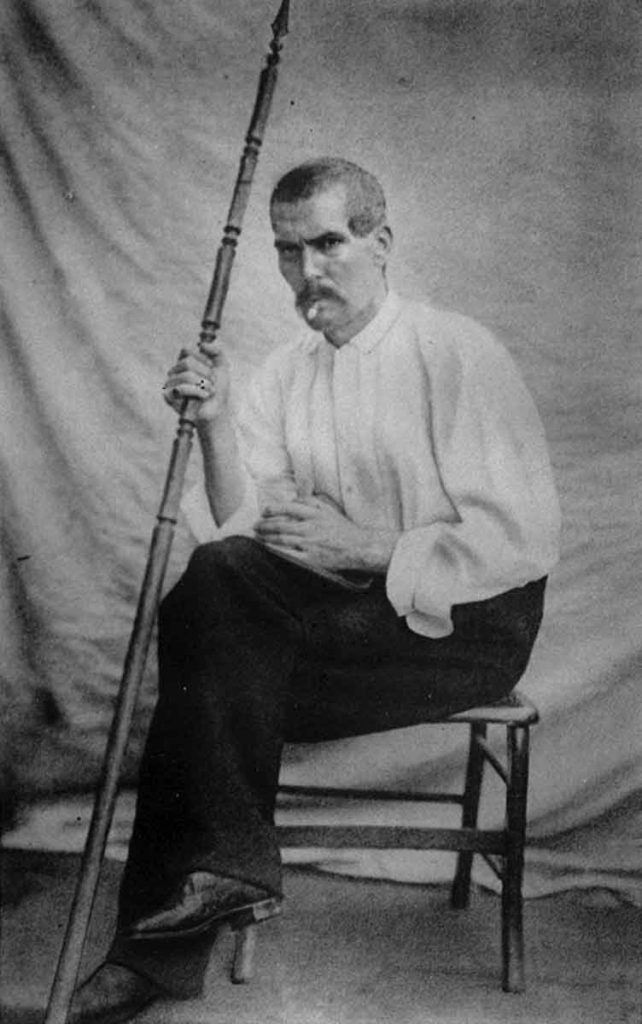

A tall dark, handsome and fearsome-looking man with a full Victorian moustache, Burton, on the surface, is like some romantic character from a Boy’s Own annual, or a vintage Hollywood swashbuckling hero. But he was also an out and out oddball, to say the very least. Notoriously and completely obsessed with sex in its every incarnation, his travel writings tell much more about the sexual practices and techniques of the people he saw on his travels than the places he visited. One can only imagine this swarthy Victorian’s reaction on meeting exotic Asian ladies desirous of his attention.

Richard Francis Burton was born on 19th March 1821 in Torquay, to Irish born Lt Colonel Joseph Netterville Burton and Martha Baker, heiress of very wealthy squire Sir Richard Baker. As a child, he and his family lived in England, Italy and France, the boy for the most part tutored privately, where his incredible ability to learn languages quickly became apparent. During his adolescence, he acquired French, Italian, Neapolitan, Latin and a host of dialects and, after a teenage romance with a Gypsy lassie, even picked up Romani. He called himself “a waif, a stray… a blaze of light, without a focus,” and proclaimed “England is the only country where I never feel at home.”

Burton entered Trinity College, Oxford in 1840 where, always an outsider, he found himself at odds with other students; after one cad ridiculed his facial hair, Burton challenged him to a duel. He studied Arabic, falconry and fencing and, after attending a steeplechase banned for all pupils, was expelled from the college. He often quoted from The Kasidah – a traditional Arabic poem that he passed off as a translation, though in fact had written himself: “Do what thy manhood bids thee do, from none but they self expect applause.” He riled the Dons by speaking the real Latin, instead of the artificial English version, and, having learnt Greek from an Athenian merchant in Marseilles as a teenager, spoke Greek Romaically, with the accent of Athens – all of which showed his remarkable ear for language and staggering memory.

Burton enlisted in the army of the East India Company because, as he put it, he was “fit for nothing but to be shot at for six pence a day.” So as a subaltern officer in the 18th Regiment of Bombay Native Infantry, he slipped off to what is now Pakistan to fight England’s war with the Sindh. While in the army, he kept a gaggle of tame monkeys and hoped to learn their language, but gave up after learning “no more that 60 words”. He became fluent in Arabic, Hindi and Punjabi and more than proficient in Marathi, Sindhi, Telugo and Pashto. He participated in the culture and traditions of India so enthusiastically that his fellow soldiers reproached him for “going native.” His nickname was ‘Ruffian Dick’, for he was a “demonic and ferocious fighter who fought in single combat more enemies than perhaps any other man of his time.”

Such aptitude curried favour with Major General Charles Napier, then commander of the British forces in Sindh, who made Burton his preferred intelligence officer. Burton, now a Captain, was sent, disguised as a Muslim trader under the adopted alias of Mirza Abdullah, into the bazaars and cafes in search of information. One such mission in 1845 required going under cover and reporting on the goings on of a male brothel in Karachi frequented by British soldiers. Burton’s overly detailed report of the bordello and its machinations strongly suggested he had taken a sizeable bite out of the forbidden fruit and availed himself thoroughly of the myriad services on offer. The report not only resulted in the demolition of the male knocking shops but also Burton’s army career, as his written testimony was forwarded to Bombay by an ill-disposed officer who’d hoped for the nonconformist’s dismissal and consequent disgrace. The effort to get rid of Burton failed but, now entirely cognisant of his damaged reputation, he returned to England, ill and even more disconsolate.

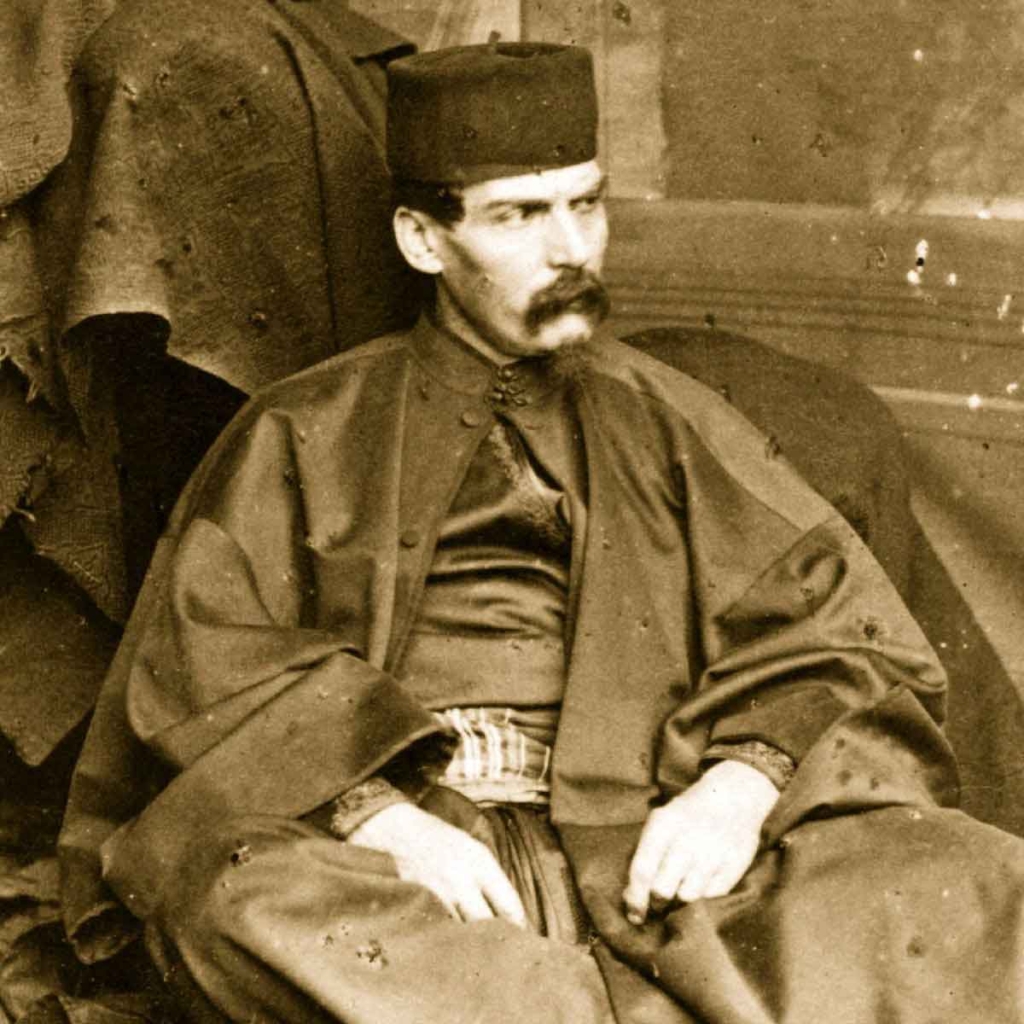

For the next three years he lived with his mother and sister in Boulogne but, far from idle, smashed out four books on India. Burton, although quill in hand, was earnestly planning a visit to Mecca, which at the time was prohibited to all non-Muslims. The intrepid explorer, disguised as a Pathan – an Afghani Muslim – darkened his skin and donned Islamic robes and, now circumcised to prevent detection, travelled to Cairo and then on to the Suez, Medina. At great personal risk, he then took the famed bandit route to Mecca, where he might have at any time been apprehended by cutlass wielding brigands who’d slit a traveller’s throat just as soon as look at them. Burton fended off such outlaws with pistol and sword.

During his visit it was claimed that, one night, when he lifted his robe to urinate rather than squatting as an Arab does, he was spotted by a local, and in order to avoid capture, killed him. Burton denied the accusation, underlining the fact that had he killed the boy he would almost certainly have come a cropper. Years later, when a man of the cloth asked about the episode Burton replied, “Sir, I’m proud to say I have committed every sin in the Decalogue.”

Yet Burton’s work was unimpeachable. His pilgrimages to El-Medinah and Mecca (1855–56) were hailed as a highly regarded commentary on Muslim life and manners. “The more haughty and offensive he is to the people, the more they respect him; a decided advantage to the traveller of choleric temperament,” wrote Burton, revealing his modus operandi. “In the hour of imminent danger, he has only to become a maniac, and he is safe; a madman in the East, like a notably eccentric character in the West, is allowed to say or do whatever the spirit directs. Add to this character a little knowledge of medicine, a moderate skill in magic, and you appear in the East to peculiar advantage.”

But for Ruffian Dick this just wasn’t enough, so he prepared a new and equally dangerous solo excursion to the equally forbidden East African city of Harer, Somalia and became the first European to cross the threshold of this Muslim citadel without being put to death in grizzly fashion. The Somalis believed a prophecy that the city would fall into ruin if a Christian entered.

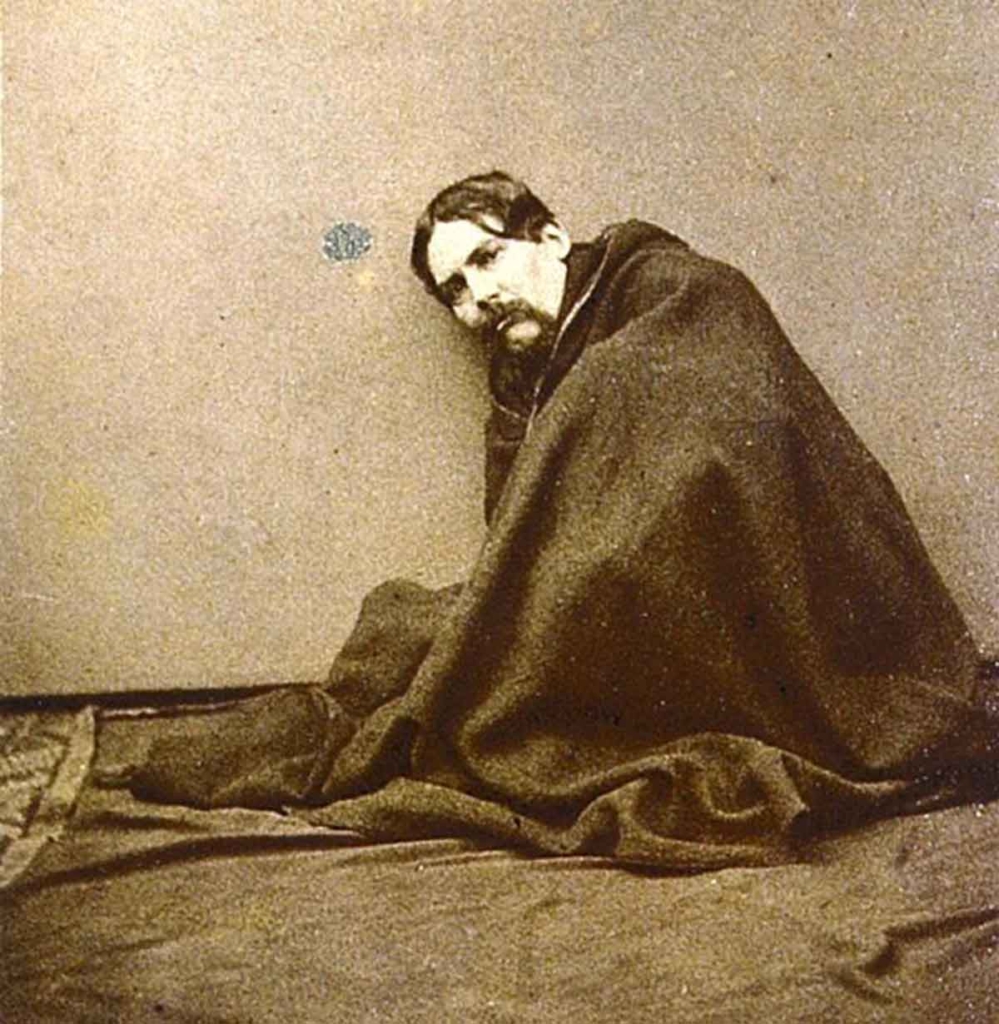

In Burton’s day the concept of discovering the source of the White Nile was all the rage. Burton, with three officers from the British East India Company, intended to travel through land but they were attacked by 200 furious locals armed with machetes and spears. Burton was felled by a well-aimed javelin that went through one cheek and out the other, leaving pronounced scars. His comrades either killed or captured, Burton was forced to return to England.

After just a few months in recovery, Ruffian Dick was off again, having volunteered to fight the Russians in the Crimea. He was part of Beatston’s Horse, a regiment of indigenous fighters in the Dardanelles who, after refusing to obey orders, disbanded while the ever-recalcitrant Burton was named in the consequent enquiry and further prejudiced against. Even though he still had the source of the Nile firmly in the front of his mind, he proposed to Isabel Arundell and, despite her father solidly refusing the union due to Burton’s irascibility, his lack of funds and his non Catholic status (on the quiet he’d become a Sufi Muslim), she acquiesced.

It took Burton another six months to find a relatively safe route into the interior, which with Lieutenant John Hanning Speke he followed on 27th June, 1857, heading west in search of the lake or lakes. The outward journey was plagued with tribulations – valuable supplies were stolen- and both men were beset by a deadly assortment of tropical diseases, snakes, big cats and hostile tribesmen. Speke was rendered blind and deaf in one ear for some of the journey, while Burton was so ill from malaria that he was unable to walk and had to be carried by bearers. Nonetheless, in February 1858, much the worse for wear, they became the first Europeans to reach Lake Tanganyika.

On their way back, after a rancorous disagreement, Speke, still blind and half deaf, left his companion and travelled north and, on July 30th, reached this great lake that he named Lake Victoria. Although disputed by many as the source of the Nile at the time, it was honoured by the Royal Geographic Society. The affair sparked a long, heated and very public animosity between Burton and Speke. Speke claimed that Burton had poisoned him on the excursion, while Burton claimed that Speke’s measurements and calculations were inaccurate. Speke died of self-inflicted gunshot wounds while hunting in 1864. The coroner ruled out suicide but most others did not.

In August 1869 Burton sailed to the United States, crossed the Missouri River and onto Salt Lake City by mail coach, to satiate his unquenchable thirst for knowledge of sexual practices. On this occasion, he’d journeyed to investigate the polygamy of The Mormons. However, having witnessed just drab day-to-day polygamy and not the expected wild orgies, Burton left the area unimpressed.

This was the last of Burton’s big escapades. He married Isabel and was appointed consul at Fernando Po in the island of Bioko in Equatorial Guinea, Central Africa, from where he explored the West African coast. His next posting was as consul for Damascus, where his efforts to keep the peace between the Muslim, Jewish and Christian populace often incurred enmity. Typically, Burton ruffled more than a few feathers and, in 1871, was transferred to Trieste, then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, a position that required little diplomacy.

Burton was awarded a knighthood on 5th February 1886 by Queen Victoria. Just four years later, he died of a heart attack in Trieste on 20th October 1890, aged 69. Isabel burned many of her husband’s papers and manuscripts after his passing, including extensive journals and a new provocative translation of The Perfumed Garden to be called The Scented Garden. Universally condemned, she later claimed that her husband had spoken to her from the grave and asked her to burn his writings. The couple are buried in a remarkable Bedouin tent-shaped tomb in Mortlake Cemetery, Richmond, London.

Sir Richard Francis Burton, 19th March 1821–20th October 1890

An amazing and uplifting article by the one n only Chris Sullivan..! Can you imagine if times were transposed that Richard Burton had written one on Chris. ! Pg

A man unique to this day