Chris Sullivan on how the end of WWI and the Spanish Flu pandemic brought about the birth of nightclub culture in 1920s London.

The nightclub ethos as we now perceive it, with bars and dance floors on which men and women actually dance together, began in the 1920s. Before the era, aptly named the Jazz Age or the Roaring Twenties, so-called ‘respectable’ women did not frequent late night venues, were not allowed into pubs and were not expected to trip the light fantastic. Their position in life was to make babies and clean the house. For the most part, the nearest thing to a nightclub prior to WWI was a barn dance or a pub with a pianist.

The roar of the twenties was not just heard in the UK but all over the world, as folk rose up from the intolerable misery of the First World War, which had left 20 million dead and some 21 million wounded. Hostilities had ended on 11th November 1918, only to be replaced by another equally insidious confrontation: Spanish Flu originated in Kansas City in March 1918 and was exported to Europe by US soldiers. First reported in a Spanish press unhindered by the US propaganda machine, the US brazenly attempted to shift the blame by sneakily naming it the Spanish Flu.

For most of us, the realities of a global pandemic were unknown in the 21st century, but now we can easily empathize with those in the 1920s who had suffered the greatest pandemic in history and how eager they were to dress up, fly out and finally get back on the lash. The result was the greatest global explosion of hedonism, art, music, style and libertarianism that had ever been witnessed. Major cities across the world went doolally: Berlin, New York, Chicago, Paris, Vienna and, last but not least, London, took the bulls by their wilting horns and gave them a damn good thrashing. And, for once, it was young women who led the way.

In 1918 the Representation of the People Act was passed in the UK, which allowed women over the age of 30 to vote. This was only 2/3 of the female population. Meanwhile, on 18th August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment was passed in the US that allowed all white female US citizens over the age of 21 to vote. Understandably, young women in the UK were furious. Thus, as an act of defiance, many aped their American counterparts by bobbing their hair, wearing shorter skirts, smoking, listening to jazz, and flaunting their disdain for contemporary mores by dancing and drinking and misbehaving in the many night clubs that sprang up around them.

Nicknamed ‘Flappers’ (derived from the way dancers of the Charleston flapped their arms) were far more controversial than the later rockers, hippies or punk rockers, and caused even greater hullabaloo. Hairdressers flourished, as millions of young ladies cut their hair. The cosmetic industry boomed, as did the tobacco business. The flapper look, also called garcon (little boy) was seized on by Coco Chanel and involved binding the chest to flatten the breasts, while waists dropped to the hipline over Rayon (artificial silk) stockings, worn rolled over a garter belt. By night, flappers frequented jazz clubs and relished casual sex. These reckless, style-obsessed flapper girls were perceived as a huge threat to a society in which women were expected to be seen and not heard.

These young flappers needed a stage where they could define themselves. This showground podium became the nightclub. Here they could dance, drink and dally without men. In nightclubs, for the first time in history, they could be themselves, and this was most certainly true in London.

In 1912, Frida Uhl Strindberg (she’d been married to Swedish playwright August Strindberg) opened the Cave of The Golden Calf in London, in a former cloth warehouse at 9 Heddon Street, just off Regent Street. Its purpose was “for the promotion of the arts and for the association together of artists and other persons who are interested in literature and the arts”. Jacob Epstein, Wyndham Lewis and Eric Gill created the club’s murals, while drinking and dancing until dawn was de rigueur for both aristos and bohemians, against a soundtrack of ragtime and a famously overexcited gypsy fiddler of dubious extraction. The spot went bankrupt in 1914 but had set the scene for the dance-crazy, frenzied 1920s, when folk threw every caution to the wind.

In 1921, the draconian wartime licensing laws that restricted opening hours to lunchtime (12:00-14:40) and supper (18:30-22:30) were reformed by Lloyd George. One could now drink till 1 am, as long as the booze was served with a meal. As one might expect, that ‘meal’ was generally sandwiches and few observed last orders.

The Dangerous Drugs Act of 1920 criminalised the selling and possession of morphine and cocaine unless on prescription. Previously both were sold over the pharmacy counter – heroin (diamorphine) as a painkiller and cough medicine, while cocaine was freely available as a pick-me-up and cure-all. “Can I have a comb, some shampoo, a tube of tooth paste please? Oh, and seven grams of cocaine and a large bottle of heroin please?” A popular medicine was Ryno’s Hay Fever Relief, which contained 99.9 per cent pure pharmaceutical grade cocaine.

Thus, unaware of the harm it might cause, cocaine was given to British troops as ‘Forced March Tablets’. “A Useful Present for Friends at the Front” announced Harrods, advertising a kit that included packages of morphine and cocaine, complete with syringe and spare needles. Such was the problem among officers that, on May 11, 1916, the Army Council issued an order banning the sale of cocaine to any member of the armed forces unless prescribed. But once back on Civvy Street, their attachment to the drug knew no bounds.

One of the most contentious nightspots to capitalise was Club 43, a totally lawless all-night cocaine parlour, opened in in 1921 on Gerard Street (now Chinatown) in Soho. Owned by the great Kate ‘Mama’ Meyrick, the club catered to the nobility, politicians, the rich, artists, actors (such as the famously Sapphic Tallulah Bankhead, who described the club as “useful for early breakfasts” – breakfast time for her being about 10pm), writers, gangsters and even members of the IRA. Part of the club’s charm was its secret escape tunnel leading to Newport Place next to Leicester Square. Nevertheless, Meyrick suffered numerous fines for selling alcohol after-hours and five prison sentences, including 15 months in Holloway in 1929 for bribing the constabulary.

In particular, Meyrick entertained a motley crew of terribly posh, sexually ambivalent young Old Etonians and Harrovians and debutantes dubbed The Bright Young People.Included in this gayest of gaggles were Edith and Oswald and Sacheverell, Elizabeth Ponsonby, a few Guinness heirs, Babe Plunkett Greene, ‘It’ girl Brenda Dean Paul and bull dyke Ruth Baldwin, both famous for their drug abuse. Also among the Bright Young Things were camp stately homos such as Cecil Beaton, the Hon Stephen Tennant, bisexual composer John Betjeman, US railroad heir and surrealist patron Edward James and Evelyn Waugh, who immortalised Meyrick as Ma Mayfield in Brideshead Revisited.

The Bright Young People took to racing through the streets of London in their Bugatti and Rolls Royce sportscars at 80mph. They held all-night parties in swimming baths, costume balls in stately homes and staggered from club to club in London’s West End. The quintessential BYP venue was the Gargoyle Club on 69 Meard Street, which claimed to transform ordinary people into Bohemians. “They even began to dress differently,” wrote Daphne Fielding.

Also in Soho was the Blue Lantern in Ham Yard, catering to the fringes of pseudo-smart Bohemia. Another Ham Yard club was The Hambone, run by Soho burglar Mark Benney, who said in his autobiography Low Company that the club “was patronised by everyone from Augustus John to Darby Sabini [Italian gangster immortalised in both Brighton Rock and Peaky Blinders]. It was arty, respectable and risqué.”

Twenties London also produced more upmarket venues such as the painstakingly decadent Kit-Kat club. Europe’s most luxurious and expensive night spot, it opened in the Haymarket in 1925 and, with a seating capacity of 1700 and a membership of 6000, became the hub of the capital’s night life, attracting princes, ministers London’s aristocracy with entertainment including singers, dancers and acrobats (such as Archibald Leach who later became Cary Grant). It was all very Great Gatsby.

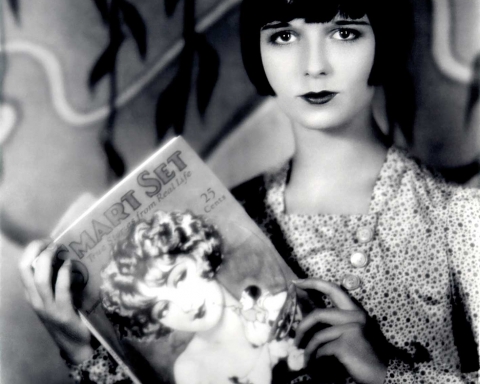

The city’s most expensive and exclusive nightspot, however, was the Embassy Club on Old Bond Street, which attracted The Prince of Wales, later King Edward VIII. The Café de Paris, opening in 1924, was so popular with the Prince and the Bright Young People that, when its popularity started to wane, the owner begged Edward to grace its dancefloor to help resuscitate the club, which he did and the club once again boomed. In 1924 New York’s Ace Face Louise Brooks visited London, demonstrated new dance craze The Charleston on stage at the Café de Paris, started a nationwide craze and was embraced by the Bright Young Things. Brooks found them rather dull and, after reading Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies, remarked, “Only a genius could write a masterpiece out of such glum material”.

After the clubs, the Bright Young Things would pile into the Cavendish Hotel on Jermyn Street, whose chatelaine Rosa Lewis was more than accommodating with drinks and all-night refreshments, courtesy of celebrity drug dealers Brilliant Chang and Eddie Manning, to keep the party alive and kicking only to wake the next evening and find their antics in the newspapers.

By the end of the twenties, the Flappers had successfully flouted their emancipation in nightclubs all over the world and there was no going back. In 1928 all women over 21 were given the vote in the UK and the world became a different place. In 1929 the Wall Street Crash brought a close to many rich people’s decadence and many clubs, such as London’s Astoria, lowered their sights to appeal to a more middle-class audience less affected by the Crash. Clubs like the Hammersmith Palais became ice skating rinks or closed for good, to be replaced later by car parks and shopping precincts.

Today, history is repeating itself as many landmark clubs like the Café de Paris have shut down, but this might be premature. The smell of approaching hedonism is in the air; undoubtedly an army of revellers are already considering what to wear when clubs and music venues are once again fully open, and much high jinks and the copious consumption of liquor seem on the cards. Will we see a return of the enthusiasm that fuelled the decadent 1920s nightclub scene? I think we’d be foolish not to think so.